Setting Up and Running a School Library

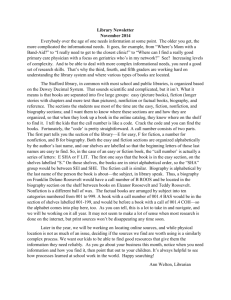

advertisement