Library Newsletter November 2014

advertisement

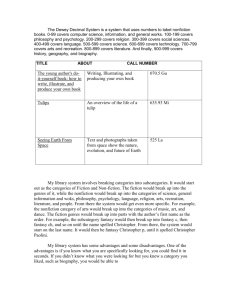

Library Newsletter November 2014 Everybody over the age of one needs information at some point. The older you get, the more complicated the informational needs. It goes, for example, from “Where’s Mom with a Band-Aid?” to “I really need to get to the closest clinic!” to “Where can I find a really good primary care physician with a focus on geriatrics who’s in my network?” See? Increasing levels of complexity. And to be able to deal with more complex informational needs, you need a good set of research skills. That’s why the third, fourth, and fifth graders are working hard on understanding the library system and where various types of books are located. The Stafford library, in common with most school and public libraries, is organized based on the Dewey Decimal System. That sounds scientific and complicated, but it isn’t. What it means is that books are separated into five large groups: easy (picture books), fiction (longer stories with chapters and more text than pictures), nonfiction or factual books, biography, and reference. The sections the students use most of the time are the easy, fiction, nonfiction, and biography sections; and I want them to know where these sections are and how they are organized, so that when they look up a book in the online catalog, they know where on the shelf to find it. I tell the kids that the call number is like a code. Crack the code and you can find the books. Fortunately, the “code’ is pretty straightforward. A call number consists of two parts. The first part tells you the section of the library—E for easy, F for fiction, a number for nonfiction, and B for biography. Both the easy and fiction sections are organized alphabetically by the author’s last name, and our shelves are labelled so that the beginning letters of those last names are easy to find. So, in the case of an easy or fiction book, the “call number’ is actually a series of letters: E SHA or F LIT. The first one says that the book is in the easy section, on the shelves labelled “S.” On those shelves, the books are in strict alphabetical order, so the “SHA” group would be between SEI and SHE. The fiction call is similar. Biography is alphabetical by the last name of the person the book is about—the subject, in library speak. Thus, a biography on Franklin Delano Roosevelt would have a call number of B ROOS and be located in the biography section on the shelf between books on Eleanor Roosevelt and Teddy Roosevelt. Nonfiction is a different ball of wax. The factual books are arranged by subject into ten categories numbered from 001 to 999. A book with a call number of 001.4 BAS would be in the section of shelves labelled 001-199, and would be before a book with a call of 001.4 COH—so the alphabet comes into play here, too. As you can tell, this is a lot to take in and navigate, and we will be working on it all year. It may not seem to make a lot of sense when most research is done on the internet, but print sources won’t be disappearing any time soon. Later in the year, we will be working on locating online sources, and while physical location is not as much of an issue, deciding if the sources we find are worth using is a similarly complex process. We want our kids to be able to find good resources that give them the information they need reliably. As you go about your business this month, notice when you need information and how you find it, then point that out to your children. It’s always helpful to see how processes learned at school work in the world. Happy searching! Ann Welton, Librarian