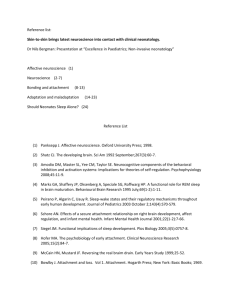

object relations, dependency, and attachment

advertisement