A Psychodynamic Guide for Essential Treatment Planning

advertisement

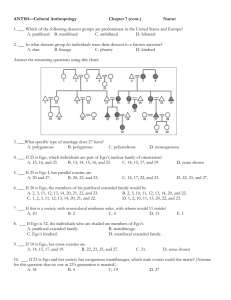

Psychoanalytic Psychology 2000, Vol. 17. No. 2, 336-359 Copyright 2000 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 0736-9 73 5/00/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0736-9735.17.2.336 A Psychodynamic Guide for Essential Treatment Planning Frank Trimboli, PhD University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and Dallas, Texas Kenneth L. Farr, PhD University of Texas at Arlington and Arlington, Texas This article presents a model for conceptualizing psychopathology designed to assist practitioners in evaluating patients and applying effective treatment plans. The model describes psychopathology as a function of (a) level of ego organization and (b) character style. Two adjunctive variables are discussed that augment treatment planning through (a) evaluation of the individual's current level of adaptive functioning and (b) confirmation of the diagnostic conceptualization and treatment approach by evaluation of the primary dynamic or conflict. These 2 major dimensions and 2 adjunctive variables are examined in relation to theoretical description of psychological functioning and procedures for assessment and treatment considerations, respectively. Key guidelines for the treatment of prototypical disorders are presented. In this era of clinical expediency induced by managed care, practitioners are sadly encouraged (or forced) to eliminate procedures thought by Frank Trimboli, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Division of Psychology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, and independent practice, Dallas, Texas; Kenneth L. Farr, PhD, Student Health Services and Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Arlington, and independent practice, Arlington, Texas. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Frank Trimboli, PhD, 4201 Spring Valley Road, Suite 1100, Dallas, Texas 75244. 336 PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 337 business managers to be nonessential. In addition to the decline of psychological testing that has been witnessed in recent years, there often exist strong pressures to eliminate the entire diagnostic process and move immediately to providing interventions, often limited by managed care companies to a handful of psychotherapy sessions. Unfortunately, the pressure to plunge blindly into psychotherapy dramatically undermines therapists' abilities to choose and apply appropriate treatment. We are in agreement with Butcher (1997) who stated, "The primary factor that the therapist can use to prevent.. . [treatment destructive forces] or at least try to counterbalance them is to obtain a clear assessment of the patient's problems," (p. 332) and who has argued for the necessity of personality assessment as a prelude to effective psychological intervention. Despite his well-reasoned arguments, there are many situations in which formal psychological testing is not possible or, increasingly, not permitted. Regardless, therapists need a coherent and comprehensive framework in order to select and apply the best possible treatment and to predict and manage stumbling blocks to achieving positive therapeutic outcomes. Such a framework becomes even more essential when working within constrictions imposed by managed care. We hope that the guide presented herein can complement formal psychological assessment results when they are available and provide an effective framework for treatment planning when they are not, regardless of whether one is working within or outside of a managed care environment. This article presents a treatment planning model based on conceptualization of psychopathology via an integration of two broad streams in psychoanalytic diagnosis. These streams are Id Psychology, as developed by Freud and expounded on by numerous authors, including Abraham (e.g., 1924) and Fenichel (e.g., 1945); and Ego Psychology, which is rooted in Freudian structural theory (1923/1961), is most closely associated with Hartmann (e.g., 1958,1964), and is articulated and explicated by numerous authors, including Blanck and Blanck (e.g., 1974) and Kernberg (e.g., 1975, 1984). In the view of Id Psychology, all human behavior (including thought) is in the service of drive gratification. In this view, human capacities such as thinking and interpersonal relations develop as a compromise forced by the demands of reality that often preclude immediate drive gratification. Although the economic assumptions underlying Id Psychology have been largely repudiated (Ricoeur, 1970; Schaffer, 1976; Tyson & Tyson, 1990, p. 42), the model for the stages of psychosexual development inherent within this formulation remains useful for the conceptualization of particular 338 TRIMBOLI AND FARR types of character styles. The stage model posits a psychosexual developmental process in which the primary source of id gratification centers on various bodily organs and the functions related to those organs in a biologically predetermined sequence. More importantly, developmental disturbances experienced during these periods, including trauma or excessive or inadequate gratification, are thought to result in distinct types of psychopathology (Fenichel, 1945). Although the stage model of psychosexual development based in Id Psychology has been useful for providing descriptive characterological diagnoses, it has proven inadequate for the conceptualization of the broadened array of patients that psychoanalysts and psychotherapists have begun to treat during the last several decades. Despite attempts to extend the psychosexual stage model to describe different levels of pathology (e.g., Zetzel, 1968), these patients present pathologies that do not readily conform to the diagnostic classifications derived from the Id Psychology model (i.e., the classic neuroses). Patients whose problems are rooted in the vicissitudes of structural development in the earliest months and years of life have required an extension of the diagnostic system to take into account problems based on deficiencies in self and object representations and problems in the capacity for functional organization of the psyche in meeting demands of reality. This is where the work of later ego theorists has provided a bridge to extend application of psychoanalytically directed treatment to a wider array of patients. Consistent with prior conceptualizations (Sandier & Rosenblatt, 1962), we use the word ego to refer to the repository of both the adaptive functions of the psyche and internal representations of self and object. Psychopathology characterized by deficiencies and disturbances in the ego or its functions has been most thoroughly explicated by Kernberg (e.g., 1975, 1984), who has addressed the need for conceptualization along a spectrum of ego development, particularly in terms of the effective treatment of patients with borderline conditions (e.g., Kernberg, 1984, p. 3). Kernberg has demonstrated that the borderline conditions can be characterized (and differentiated from neurotic and psychotic conditions) according to several well-accepted characteristic aspects of ego stucturalization discussed below. In this article, we present a framework that integrates Id and Ego Psychology lines of development in the conceptualization of psychopathology for the purpose of guiding treatment. The simultaneous incorporation of id and ego lines of development has been addressed previously (e.g., Lerner, 1991; McWilliams, 1994, pp. 29-40; Smith, 1978). We propose PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 339 that diagnostic conceptualization and ultimate treatment goals should be flexibly guided by consideration of two major dimensions: (a) level of ego organization and (b) character style. Furthermore, the patient's current level of adaptive functioning can augment the pursuit of these goals by suggesting specific treatment considerations and approaches that can prove useful in strategic treatment planning, whereas evaluation of the patient's primary dynamic or conflict can help to validate the diagnostic conceptualization and treatment approach. Part I: Diagnostic Considerations Level of Ego Organization We believe the first step in the diagnostic process should be to place an individual along the ego organization line. Although we cannot do justice to the depth and complexity of Kernberg's (e.g., 1975, 1984) formulations in this brief article, we hope that the following will elucidate those elements of his formulation that bear on our discussion of treatment planning below. For ease of presentation, three basic levels of ego organization will be delimited (neurotic, borderline, and psychotic; see Table 1). However, the reader should bear in mind that ego organization is best conceptualized as a continuum with lines of distinction that in reality are less clear than these three headings may suggest. Kemberg (1984) assessed level of ego organization according to three primary structural criteria (level of identity integration, sophistication of defensive operations, and adequacy of reality testing) and other nonspecific manifestations of ego weakness (Kernberg, 1975, 1984; see Table 1). Identity integration refers to the extent to which the individual has integrated positive and negative self introjects and positive and negative object introjects that are maintained in a relatively constant manner within the psyche regardless of temporary alterations in feelings toward these objects. In regard to self introjections, the neurotically organized individual has an ". . . inner experience of continuity of self through time," (MeWilliams, 1994, p. 54) and is able to maintain and acknowledge an understanding of positive qualities even in the face of guilt, failure, or disappointment in oneself. An individual at the borderline or psychotic level of organization is unable to integrate contradictory behavior in an emotionally meaningful way (Kernberg, 1984, p. 12) and is likely to experience pervasive feelings of worthlessness without an ability to maintain a sense of one's positive qualities or an ability to credit accomplishments at the same time. Others are perceived in a shallow, impoverished TRIMBOLI AND FARR 340 3 o o O 00 "5 >-\ (5 "c u "a u ua AH X> _D 0) B 2i 2 "-S -J3 :>v s^ =>^ ^H ^ ^ all z l l Io •C3 OH & un 0. C§ 0) a I 4> 'HO 03 oOQ 1 a it* =fi 3 a -al-a S C S W 'p S ooO-I 5 S^ 4) SB # a, :> | ^3 Sa. 0 1 S 2 f (2 C- S „ cQ 111 111 1 S a O ¥ 1 o 3 O g 13 •g § s •2 •o 2 2 M I« (^ tu ^ '"J o 00 a) o 00 ^J M CO CJ C O U Structural criteria Identity Primary defense Reality testing Nonspecific manifestation Anxiety tolerance Impulse control Sublimatory channels Other Table 1 Criteria Associated Wit •g Primitivf N .£ 3 O u I p. 3 o a o 1 w> S 'I 3 PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 341 manner, which makes it difficult for an interviewer or therapist to develop empathy (Kernberg, 1984,p. 12). An example of identity integration in the realm of object relations is the capacity to remain attached to a spouse even when enraged, representative of the neurotically organized individual. In contrast, an individual at the borderline or psychotic level must rely on the defense mechanism of splitting (see below) to protect the ego from contradictory experiences of self and others. Thus, in the case of disappointment with or rage toward a spouse, the spouse is thoroughly devalued and affectively cathected positive aspects cannot be simultaneously maintained. Though borderline and psychotically organized individuals both may be described as displaying identity diffusion, there are some differences between the two. Whereas borderline individuals' experience of self and others are fluctuating, inconsistent, and one-dimensional, psychotic individuals have even greater identity disturbance. They are likely to experience (or their actions may suggest) an even deeper confusion about themselves and others, and they may manifest an extreme fragility in the underlying sense of self such that the psychotic often feels a breath away from psychological obliteration. McWilliams (1994) pointed out that such individuals may struggle with basic issues of self-definition, wondering who they are or whether they truly exist. Defensive operations consist of two main levels: the more sophisticated version in which the individual is capable of formal repression and the secondary defenses associated with repression, and a less sophisticated version in which the individual's ego resources have not developed sufficiently to permit repression. That is, the defensive operations of the neurotic protect the ego from intrapsychic conflicts by the rejection of a drive derivative or its ideational representation from conscious awareness. In contrast, the mechanisms used by individuals at the borderline level of ego organization protect the ego from conflicts by splitting, a means of actively keeping apart contradictory experiences of the self and significant others (Kernberg, 1984, p. 15). Unfortunately, this latter type of distortion results in a serious weakening of ego functioning and a reduction in adaptation and flexibility. In the psychotic individual, the same defense mechanisms protect the individual from debilitating disintegration of mental boundaries between self and object. As described by McWilliams, splitting is clinically evident when a person "expresses one nonambivalent attitude and regards its opposite (the other side of what most of us would feel as ambivalence) as completely disconnected" (McWilliams, 1994, p. 113). For example, a borderline individual describes a colleague as wonderful, kind, and smart, but 1 week later the same individual is referred 342 TRIMBOLI AND FARR to as abusive and cold, with no acknowledgment of the discrepancy. The defense of splitting may appear in the therapeutic relationship as a patient alternately idealizes, then devalues, his or her therapist, without an experience of concern or curiosity about the dramatic change. The hallmark distinguishing feature of the psychotic individual is impaired reality testing. Questions and confusion about one's basic existence may manifest as a delusion about that existence (e.g., "I am a rat in an experiment," or "I am Jesus Christ."). The disturbances in identity can be so profound that one may be unsure of where their own existence stops and another's begins, leading, for example, to delusions of thought control or insertion. These examples also suggest the presence of primitive defensive operations reflective of psychotic ego development such as denial of reality and withdrawal into fantasy. Note that although impaired reality testing is often blatant, it need not be. In particular, individuals with a degree of paranoia may be quite skilled at hiding signs of impaired reality testing. To the extent that an individual manifests identity integration, defenses organized around repression, and intact reality testing, the individual would be judged to have a neurotic structural organization. To the extent that an individual manifests identity diffusion, has defenses organized around splitting, yet maintains adequate reality testing, the individual would be judged to have a borderline structural organization. Finally, to the extent that an individual manifests identity diffusion, has defenses organized around splitting, and has not maintained adequate reality testing, the individual would be judged to have a psychotic structural organization. In addition to the three primary criteria described above, Kernberg (1984) identified deficits in the following ego functions as indications of borderline and psychotic adaptations (see Table 1): anxiety tolerance, referring to "the degree to which a patient can tolerate a load of tension greater than what he habitually experiences without developing increased symptoms or generally regressive behavior" (Kernberg, 1984, p. 19); impulse control, referring to "the degree to which the patient can experience instinctual urges or strong emotions without having to act on them immediately against his better judgment and interest," (Kernberg, 1984, p. 19); and developed channels of sublimation, referring to "the degree to which the patient can invest himself in values beyond his immediate self-interest or beyond self-preservation," (Kernberg, 1984, p. 19). Kemberg (1984) further indicated that although neurotic types of structural organization manifest a well-integrated (though often severe) superego, the superego integration of borderline and psychotically organized individuals PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 343 is typically impaired and marked by primitive superego precursors, particularly primitive sadistic and idealized object representations. Taken together, neurotically organized individuals are more capable of using signal anxiety, demonstrate greater impulse control, have a greater capacity for sublimation, and have a more benign superego than individuals functioning at borderline and psychotic levels of ego development. Relative to borderline and psychotically organized individuals, neurotics furthermore have a greater capacity to observe their own pathology, tend to develop transferences marked more by ambivalence than the strong yet fluctuating transferences marked by splitting, and spur countertransferences that can be easily tolerated as opposed to countertransferences that are more provocative and intense (McWilliams, 1994, p. 60). Determination of Character Style The consideration of issues related to the genetic and descriptive understanding of character style has been a central focus of psychoanalytic theory development from its inception (e.g., Freud, 1905/1953, 1915/1957; see also Abraham, 1924; Fenichel, 1945; Reich, 1933/1972; Shapiro, 1965). In his classic text, Reich (1933/1972) illustrated the extent to which neurosis can become incorporated into the character style of the individual such that the individual's characteristic manner of behaving and relating to the world reflects the ongoing defenses against underlying neurotic problems and conflicts. He and other theorists have postulated that trauma or irregularities of development in early phases of development lead to particular predictable adaptations in the context of fixation at such early levels of development. Freud's "Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality" (Freud, 1905/1953) identifies the oral, anal, and phallic levels. He, his contemporaries, and later theorists describe characteristics and particular types of psychopathology resulting from difficulties at each of these levels of development (Abraham, 1924; Fenichel, 1945). Although their original assignment of pathology has not always held true, it does appear that there are consistencies that exist within the individuals that are thought to have been fixated or suffered some arrest at a particular level. Reich (1933/1972) and Shapiro (1965) in particular have provided excellent descriptions of several neurotic character styles. Space does not permit us to comprehensively review the issue, yet we shall make some general points about the process of determining character style and about specific characteristics of oral, anal, and phallic character styles, respectively. In thinking about character style, major attributes to which one should be attendant include the nature of drives, urges, and wishes (and defenses thereagainst); styles 344 TRIMBOLI AND FARR of cognition; affective experience; and patterns of interaction. The therapist should attend to the quality of these factors in the patient's reported concerns and history and in the manner of interaction with the therapist. The manner in which the patient approaches the treatment relationship in terms of what is wished for, needed, or feared by the patient is particularly relevant. Orally fixated individuals, represented by trauma or irregularities of gratification approximately from birth through 18 months of age, have concerns that primarily revolve around dependency and soothing and exhibit excessive self-focus. Their struggles to obtain oral gratification manifest in concerns about whether their needs are being met. Anally fixated individuals, represented by trauma or irregularities of gratification approximately between the ages of 18 months to 3 years, show concerns or conflicts primarily revolving around issues of control and manipulation in the context of a dyadic dynamic in which a wish to control, dominate, or defeat others is prominent. Feelings of envy and control or containment of aggression are characteristic problems. Competition, when observed, is in the service of domination (dyadic) as opposed to winning a prize (triadic). Defensive operations involving isolation and undoing are enlisted in attempts to avoid the threat of impulses, wishes, and urges. Shapiro (1965) described individuals with anal character styles (in the neurotically organized ego range) as "automatons" because of their rigidity and loss of autonomy or free will in attempts to eliminate id-driven wishes or impulses that are experienced as threatening. Individuals with anal character styles have often been described in the literature with terms such as compulsive or obsessive-compulsive (e.g., Reich, 1933/1972; Shapiro, 1965). Individuals with phallic character styles, represented by trauma or irregularities of gratification approximately between the ages of 3 to 6 years, struggle with issues of competition, jealousy, guilt, and shame seeded in Oedipal conflict. Of the neurotic conditions, none has more definitively or clearly been associated with specific defensive operations than has hysteria with repression (Shapiro, 1965, p. 108). Individuals with hysterical character styles tend to manifest high affectivity and high interpersonal intensity (McWilliams, 1994, p. 302). The nature of the primary conflicts in these individuals is triadic and marked not only by feelings of jealousy ("I want who [or what] you have") but also by strong superego-based guilt that may result in intrapsychic anxiety and behavioral conformity or restraint. Repression of the conflict results in heightened anxiety as the individual struggles to contain competitive impulses, and PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 345 anxiety may be rooted in unconscious fears characteristic of this character style. Selected self-representations in such individuals may be marked by weakness, insignificance, and inadequacy. Defensive operations may lead to outwardly sexual, seductive, or self-aggrandizing presentations as counterreactions to such self-representations. Level of Adaptive Functioning In the process of conceptualization, it is important to consider not only issues of ego organization and character style but, secondarily, the level of adaptive functioning at which a patient presents. In our view, level of adaptive functioning is reflective of the degree to which the individual is able to maintain adaptive functioning or has become debilitated in light of underlying structural deficits, character pathology, or both. Level of adaptive functioning is reflected in the intensification and development of problems representative of the breakdown in the individual's ability to cope internally with intrapsychic conflict, thus resulting in compromises or defensive operations that are associated with maladaptive behaviors, overwhelming affects, symptom formation, or all three. Level of adaptive functioning should be thought of as a continuum from adaptively functioning (characteristically adaptive and relatively symptom-free) to fully impaired (exhibiting maladaptive debilitated functioning and full symptom formation), similar to the manner in which ego organization is represented as a continuum from neurotic to psychotic organization. However, for ease of presentation, three basic levels or degrees are differentiated. These degrees are (a) adaptively functioning, (b) partially impaired, and (c) fully impaired (see Figures 1,2, and 3). Individuals who are functioning adaptively will rarely seek treatment and will be free of disruptive and debilitating symptoms (Figure 1). Adaptively functioning neurotically organized individuals tend to be flexibly assertive and asymptomatic. When unburdened by any conspicuous fixations in character style, they represent the most healthy type of individuals. They display a healthy balance between concerns for self and concerns for others. Adaptively functioning individuals at the borderline level of ego development tend to be self-absorbed and exploitative of others, with these attitudes being completely ego-syntonic. They do not experience clinically significant depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric symptoms. Likewise, the functioning of psychotically organized individuals who are adaptively functioning is ego-syntonic. These individuals tend to be avoidant and guarded. They tend to be isolated individuals who keep 346 TRIMBOLI AND FARR Ego Development Level Neurotic Borderline Psychotic Self-Absorbed Avoidant Flexibly Oral - Assertive - And And Exploitative Guarded Anal And Asymptomatic Figure 1. Characteristics of adoptively functioning individuals. (Note: These individuals rarely seek treatment). interpersonal interactions to a minimum. They give little to others interpersonally, but neither do they make demands. Although adaptively functioning individuals display minimal overt symptom development, those who are partially impaired or fully impaired show symptom development and compromised functioning. Figure 2 Ego Development Level Neurotic Oral Anal U Phallic Intensification of Anxiety/ "Actual Neurosis"/ Depressive Personality Intensification of Anxiety/ "Actual Neurosis"/ Obsessive Personality Intensification of Anxiety/ "Actual Neurosis"/ Hysterical Personality Figure 2. " Borderline Psychotic Intensification of Intensification of Self-Protective Behavior Paranoid Guardedness And And Ruthlessness Suspiciousness Characteristics of partially impaired individuals. 347 PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE Ego Development Level Neurotic Borderline Oral "Neurotic" Depression Borderline Personality Disorder Schizophrenia/ Psychotic Depression Anal Obsessions and Compulsions Sadistic/ Masochistic/ Antisocial Personalities Paranoia (Delusional Disorder) Narcissistic and Histrionic Personality Disorders Manic- Depression/ "Hysterical Psychosis" I u Phallic Figure 3. Hysterical Conversion/ Phobia Psychotic Prototypical disorders characteristic of fully impaired individu- als. We wish to express our gratitude to Rycke L. Marshall for her assistance in delineating the placement of the prototypical disorders. displays characteristics of partially impaired individuals. In neurotically organized individuals, partial impairment is manifested by intensification of general (particularly somaticized) anxiety, feelings of listlessness and fatigue, or both. In the past these two syndromes were grouped under the heading of the actual neuroses and were referred to as anxiety neurosis and neurasthenia, respectively (Freud, 1895/]962a, 1898/1962b). Despite the fact that Freud's ideas about the pathogenesis of these two conditions have been revised (e.g., Giovacchini, 1987, p. 183), they remain descriptively useful. Fenichel (1945, pp. 185-192) also used the phrase "actual neurosis" to describe the beginning stages of a symptom disorder in neurotically organized individuals. With partial impairment, individuals whose functioning is at the neurotic level of ego organization will manifest an intensification of their depressive, obsessive, or hysterical personality traits on the basis of their basic character style (oral, anal, and phallic, respectively). Partial impairment in the face of stress for those individuals at the borderline level of ego development will result in (compared with adaptively functioning borderlines) an intensification of their self-protective behavior and ruthlessness, whereas those at the psychotic level of ego organization will manifest (compared with adaptively functioning psychotics) increased paranoid guardedness and suspiciousness. Figure 3 presents the major diagnostic classifications associated with 348 TRIMBOLI AND FARR full impairments. We believe the disorders listed to be consistent with the bulk of psychopathology literature and only prototypical of the particular categories we have delimited, not exhaustive of all diagnostic classifications. Other disorders (e.g., addictions, eating disorders), may span the boundaries of our categories. That is, in some cases an individual with these other disorders will most accurately be classified in one category, whereas other individuals will fit best into another. Full impairment in neurotically organized individuals is associated with the development of the classic neurotic symptoms. Fully impaired neurotics with oral character styles will present with serious depression, characteristics of extremely dependent personality disorder, or both; fully impaired neurotics with anal character styles will often present with distinct and ego dystonic obsessive symptoms, compulsive symptoms, or both; and fully impaired neurotics with phallic character styles often display hysterical conversion symptoms or phobias (see Figure 3). In individuals organized at the borderline level, full impairment results in the manifestation of the more severe personality disorders. Fully impaired individuals with borderline organization and an oral character style will present with an exaggeration of those symptoms classically associated with borderline personality disorder (i.e., intense, unstable, and reactive affect; intense and unstable interpersonal relationships; intense and unstable self and object representations; impulsivity; rage; and intense abandonment fears); fully impaired individuals with borderline organization and an anal character style will manifest more overt masochistic and sadistic disorders, and when further combined with serious superego deficits, antisocial patterns are exhibited; fully impaired individuals with borderline organization and a phallic character style struggle with the combination of Oedipal conflict associated with phallic character issues and deficiencies in self and object representations resulting from ego development deficits. They may well manifest severe narcissistic personalities (as described by Kernberg, 1975,1984) or the more regressive forms of the hysterical-variety personality disorders referred to in the psychoanalytic literature as hysteroid (Easser & Lesser, 1965), Zetzel type 3 and 4 (Zetzel, 1968), or infantile (Kernberg, 1975) personalities. Psychotically organized individuals, when fully impaired, exhibit overt psychotic symptoms reflected, for example, in the presence of schizophrenia, delusional disorders, and manic-depressive psychosis. Fully impaired psychotics with oral character styles will typically exhibit psychotic depression or schizophrenia; fully impaired psychotics with anal character styles tend to have paranoid or delusional disorders; and fully PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 349 impaired psychotics with phallic character styles we believe present with manic-depressive psychosis or what has been referred to in the literature as hysterical psychosis (Hollender & Hirsch, 1964; see Figure 3). Verification of Conceptualization Through Assessment of Primary Dynamics/Major Conflicts Once one has a reasonably comprehensive conceptual understanding of the pathology of the patient, it is wise to seek verification of one's diagnostic hypotheses by attending to primary dynamics reflected in the therapeutic relationship and in the content of the patient's descriptions of self, relationships, and problems. Table 2 summarizes the major points. Lest the reader be confused, we want to clarify that in our presentation of Table 2 and elsewhere (e.g., Figure 3), we discuss dynamics, conflicts, and defenses that we consider prototypical of one form of psychopathology or another, such as a particular level of ego development or a particular character style. We contend that these dynamics, conflicts, and defenses are primary to these forms of psychopathology because of their prevalence, not their exclusivity. It is common, in fact, to observe a variety of conflicts and concerns in any individual. Our formulations reflect our view that particular conflicts or concerns are more frequently associated (not exclusively associated) with particular forms of psychopathology. With regard to issues of level of ego organization, one should find in neurotically organized individuals feelings of guilt or shame as the primary dynamic; in borderline organized individuals themes of separation, abandonment, and betrayal should appear; and in psychotically organized individuals fears of annihilation and loss of self should be evident. With regard to character style, in orally fixated individuals, one should find themes of self-focus and wishes to be gratified, soothed, or taken care of. In anally fixated individuals, one should find dyadic conflicts marked by Table 2 Prototypical Primary Dynamics and Major Conflicts Dimension Ego development level Neurotic Borderline Psychotic Character style Oral Anal Phallic Dynamic/conflict Guilt or shame Separation, abandonment, betrayal Annihilation, engulfment, loss of self Self-focus: "What about my needs?" Dyadic: "I want to control/dominate you" Triadic: "T want what/who you have" 350 TRIMBOLI AND FARR wishes to control or dominate others and defenses against aggressive wishes. Lastly, in phallically fixated individuals, one should find triangular conflicts marked by wishes for and defenses against competitive strivings. Part II: Treatment Considerations When approximations of the primary dimensions and augmentative variables discussed above have been established, the following guidelines regarding treatment planning should be observed: (a) issues of ego organization and character style take precedence in treatment planning in that these issues dictate basic goals and approaches to treatment; (b) in most individuals, symptoms of full impairment must be addressed in the early treatment phases in order to involve them in the treatment process; and (c) character style considerations are most salient in dictating treatment approaches when an individual has been assessed to be functioning at the neurotic level of ego development. It should be noted that individuals with disorders thought to have a significant biological component (e.g., schizophrenia, and some forms of depression and manic-depression) will rarely seek or require treatment when symptom-free or in medication remission. Tables 3, 4, and 5 summarize the focal treatment issues. Note that this section on treatment is not intended to be a comprehensive treatise on psychoanalytically oriented therapeutic techniques but rather is intended to supplement and complement such writings by emphasizing fundamental ideas about the treatment of various forms of psy chopathology. There are a Table 3 Treatment Planning for Individuals at the Neurotic Level of Ego Development Character style Treatment considerations All styles Resolution of neurotic conflict (primary goal) Neutralization of neurotic defenses Easing of prohibitive superego Development of understanding into how symptoms are maintained Development of understanding into how symptoms create interpersonal distance Oral Treatment goals listed for all styles Encourage empathy Anal Treatment goals listed for all styles Confront content Explore affect Phallic Treatment goals listed for all styles Confront affect Explore content Note. These individuals rarely seek treatment when functioning adaptively; may need to assist in stabilization if severely fully impaired. PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 351 "a? | •2 3 j< 1 1 >. I f object consi .es :nt considerat I 1 "S C .2 bfl .a 'S .£ 'cS 6. 1 j>> 4J 3 -1 > e II ^'^ 1u f •°1 "3 S 's ° J= 1 o,-^ &| manifestation 1° is 1 6W BH C3 u 8 I | | 1 ^ « S2 e 1s «[§ -si i| 1 8 |g>| 11 •c a SS __ 3 I > *1 «|s gll - S s g 1 I f f HI HI rp u 'i « -£S 1e S «, § K o :| 'g „ >,f K ^1 | | ||1 l|| | | | ^| O-^ O~t> OB.. Oci, ^S §S 12 ^ S^l i §3 I-& (3*jS '3c^ w'Su 13 -d S "3 S c3 13 <u Js'cS iS s 6z.S P S ^ E^^S £3 ^51 sSaS sSds ^| •5 .§ *y 3 S 1 i ft 1 g| ire presenting Level ofEgc> Developme, c* §1 11 nt goals for al![ styles to aggression as primary tra iary, protect sc>ciety 1 :go developmisnt through pr i consistency «wid therapeutic o c a 1 s 1 1 fr f Q 1 •^ 1 •g 1 | | 1 OJ) -S Ofi "^ ^ 00 "5 5; •»s •*jj | l 1.1 c 1 -id o jj •B s '& 'I "«If *> 'i % It 1 s I ^ 0 'u a 5 1 1 .E '>, a _ a P 1 f •^ 1* „ „ I |3 1 | a •^ 3 •o '> 0- I 352 TRIMBOLI AND FARR Table 5 Treatment Planning for Individuals at the Psychotic Level of Ego Development Level of adaptive functioning Treatment considerations All styles Pacify Stabilize Support Functioning adaptively Treatment goals for all styles Remain at supportive level Guard against tendency to uncover and explore Partially impaired Treatment goals for all styles Reinstate and reinforce defensive functioning Consider environmental manipulation Consider medication to promote stabilization Fully impaired Treatment goals for all styles Medication and hospitalization frequently required to achieve superordinate treatment goals Once stabilized, follow prescription for partially impaired psychotically organized individual Note. These individuals rarely seek treatment when functioning adaptively. Character style issues are minimally important at the psychotic level of ego organization; ego development concerns take precedence. number of guides to the practice of psychoanalytically based psychotherapy one may wish to consult. These include the works of Friedman (1988), Greenson (1967), Kernberg (1975, 1976, 1980, 1984), Langs (1978, 1979, 1980, 1981a, 1981b), and Paul (1973, 1997), as well as numerous others. We also hasten to mention that our treatment guidelines cannot and must not be applied mechanically. Instead, they must be implemented within the context of a relationship between patient and therapist characterized by features such as empathy, respect, and collaboration. A sound therapeutic alliance/relationship is considered the essential prerequisite to treatment. If an individual is thought to be neurotically organized, the superordinate treatment goal is the resolution of the neurotic conflict. At times, however, severe impairments in adaptive functioning in neurotics must first be addressed in order to ensure an opportunity to conduct treatment. For example, life-threatening suicidal ideation may need to be dealt with directly, or serious symptoms (e.g., lethargy, compulsive rituals, agoraphobia) that interfere with the individual's attendance in therapy must be addressed. A variety of techniques may be used in helping the fully impaired neurotically organized individual reestablish a higher degree of functionality. These techniques include providing opportunities for catharsis, supportive interventions, drawing family members into treatment, PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 353 providing behavioral recommendations, prescription of medication, and hospitalization. Space does not permit a complete coverage of techniques available to address these treatment limiting factors, but the reader is encouraged to consult other sources (e.g., Bellak, 1992; Puryear, 1979). Most neurotically organized individuals have the capacity and stability to tolerate intensive exploratory treatment without inducing further functional impairment. Thus, to the extent that the patient's symptomatology is not so severe as to put life in danger or disturb functioning to the point of interfering with the patient's ability to attend therapy, it becomes necessary to focus on the accomplishment of the superordinate goal (i.e., resolution of the neurotic conflict). To achieve the superordinate goal, one must help the individual to neutralize neurotic defenses, address superego prohibitions, assist in the development of understanding into how the expression of symptoms is maintained, and promote understanding into how symptoms create or maintain interpersonal distance. Each character style is associated with particular types of defenses, styles of superego functioning, symptoms, and self-defeating patterns by which these symptoms maintain interpersonal distance. Table 3 summarizes the major points. Neurotically organized individuals with an oral character style can benefit most from a treatment approach that encourages the development of empathy because these individuals are excessively self-focused. Their neediness and dependency interferes with their ability to form mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships. In other words, individuals with this character style have an insatiable hunger that leads to an excessive focus on one's own needs and excludes a reasonable consideration of others' needs. Passivity may need to be addressed in the oral neurotic, who may become passive secondary to a fear that expression of aggression will result in the loss of a needed source of gratification. Treatment of neurotically organized individuals with an anal character style must take an approach that confronts the defensive use of cognition (the more common defense mechanisms being intellectualization, obsessive doubting, compulsivity, etc.) and encourages the exploration of emotion. Intellectualization must be curtailed, and doubting and procrastination must be addressed. This sometimes begins with a basic labeling process whereby bodily sensations experienced by the individual are labeled by the therapist with affectively descriptive terms. Superego prohibitions of aggression are common and defended against through the mobilization of attempts to isolate id urges and channel them into rigidly controlled intellectualized pursuits. Passivity may also be a problem; the individual unconsciously experiences danger in the destructive force of his 354 TRMBOLI AND FARR or her own aggression and overcompensates for or suppresses it. Thus, as in the treatment of an oral neurotic, passivity may need to be addressed, though the underlying dynamics differ: Passivity in the anal character style occurs out of fear of the sheer destructive force of one's aggression, whereas passivity in the oral character style is more need-driven in that the experienced threat is related to the fear that expression of aggression will result in the loss of a needed source of gratification. Treatment of the anal neurotic must involve the gradual development of insight into underlying threatening emotions. Neutralization of cognitive defenses helps this to take place. Successful treatment will also address the interpersonal distance (rigidity and lack of emotional involvement) that results from the anal dynamism. In contrast to the treatment approach discussed immediately above, treatment of neurotically organized individuals with a phallic character style must involve confrontation of the defensive use of affect in order to neutralize the defenses, thereby allowing for an exploration of the content of one's wishes and thoughts, which will encourage the development of logical thought and causal thinking. In these individuals, superego prohibitions of sexualized and competitive wishes often lead to the repression of such wishes, which are often masked with excessive emotionality, confrontation of which will help neutralize such defenses, providing an opportunity for increased self-understanding. Table 4 displays the focal issues in the treatment of individuals functioning at the borderline level of ego development. In the treatment of such individuals, promotion of object constancy always should be the overriding goal. To achieve this, the maintenance of consistent and clear therapeutic boundaries is essential when performing psychotherapy. Unfortunately, borderline organized individuals suffer from significant functional impairments more frequently than those with neurotic ego organizations, and the impairments are often associated with life threatening symptoms that demand urgent attention. One may find oneself forced into a crisis intervention mode of treatment as opposed to psychotherapy. Medication may provide a modicum of stability through which treatment can be enhanced. Adaptively functioning individuals organized at the borderline level rarely present for treatment because their problems tend to be ego syntonic. When they are distressed, they typically see their upset as a legitimate reaction to their circumstances, or they perceive they have been provoked by others. Therefore, when they do present for treatment, it is often a mandated participation, perhaps ordered by a court of law, or occasionally PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 355 at the urging of a spouse or family member. It is typically very difficult to engage such individuals in the treatment process (i.e., they are not open to the formation of a working alliance). The general guidelines provided below for the treatment of partially impaired borderline individuals should be borne in mind, though in cases of highly resistant individuals the heavy use of didactic approaches may be of benefit; at least the individual may learn something that they may make use of at a later time when they are more open to alternative modes of thinking or behavior. Partially impaired and fully impaired borderline organized individuals present some of the greatest challenges to psychotherapists and are often considered to be "difficult" patients. They may be experienced as demanding, unstable, ruthless, manipulative, exploitative, seductive, dangerous, etc. Treatment of borderline organized individuals when they are partially impaired must address and confront the use of splitting (a direct consequence of the lack of object constancy) as the primary defense mechanism along with nurturing and supporting higher level defensive operations when any evidence of them is observed. Moreover, an examination of acting out behavior will often help the individual to understand triggers and self-defeating consequences to these behaviors. Lacking in skills, these individuals may need to be taught alternatives to acting out. When fully impaired, ego functioning in borderline individuals may be so seriously impaired that the individual is functioning much as a psychotic individual might. In these cases, it becomes necessary to treat the individual as if he or she were indeed psychotic (see below). When the individual regains a modicum of stability, one can transition to treating the individual according to the guidelines for partially impaired individuals at the borderline level of ego organization. Character style influences can often be observed in partially impaired and fully impaired borderline organized individuals, and although issues related to character style are secondary in importance to those related to ego deficits in the conceptualization and treatment of these individuals, they are nonetheless important. In an orally fixated, partially impaired borderline organized individual, for instance, one must be alert to intense engulfing transferences and to the possibility that such individuals may engage in self-destructive (e.g., self-mutilating) acts. The danger of selfdestructiveness becomes particularly acute when the individual is judged to be fully impaired, at which point it is highly likely that steps may need to be taken to ensure the safety of the individual (e.g., hospitalization). Individuals in this category at times may also pose a threat to the physical safety of others, against whom unmodulated rage may be directed. (Note 356 TRIMBOLI AND PARR that risk of self-destructiveness in these individuals is greater than risk to others, though the reverse is true for fully impaired anally fixated borderline individuals; see below). In tandem with addressing risk of harm to the patient and others, one should look for opportunities to confront appetitive instability in order to help the individual develop some degree of ego awareness and, thus, hopefully, affective modulation. In partially impaired and fully impaired borderline-organized individuals who are anally fixated, one must be alert to aggression in the transference, which can threaten the treatment. And in some cases of partially impaired and many cases of fully impaired borderline individuals with an anal character style there may be a danger that serious and/or poorly modulated aggression may present a danger to others, and the therapist will need to consider the appropriateness of taking steps to protect potential victims. One should look for opportunities to confront and neutralize aggression in these individuals. A primary concern in the treatment of partially impaired and fully impaired borderline individuals with a phallic character style is likely to be the management of idealization in the transference. Recall that these individuals typically present with narcissistic disorders. Though there is some debate in the literature (with Kernbergians on the one side [e.g., Kernberg, 1975, 1976, 1984] and Kohutians on the other [e.g., Kohut, 1971, 1977; Kohut & Wolf, 1978]) about the most effective treatment techniques for dealing with the idealizing transferences of narcissistic individuals, there is little argument that it must be addressed. Table 5 indicates that character style issues are of only minor importance in the treatment approach of individuals assessed to be functioning at a psychotic level of ego development. Because of the severity of ego deficits in these individuals, which leaves them susceptible to disorganized and fully impaired functioning, treatment considerations must focus foremost on dealing with the weak ego, along with a consideration of the level of adaptive functioning. The superordinate treatment goals for individuals who are psychotically organized should emphasize pacification, stabilization, and support because of the fragility in the ego and the tendency for these individuals to decompensatc along the ego line of development. Medication is commonly necessary. Psychotically organized individuals who are adaptively functioning rarely seek treatment. When they do, it is important to remain at the supportive level therapeutically. There may be a temptation to explore and uncover and to establish a treatment environment (e.g., including neutrality and transference interpretation) more appropriately suited for neurotically PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 357 organized individuals because the individual may outwardly seem stable and may exhibit only very subtle signs of reality impairment that can be easily overlooked. Perhaps the individual appears slightly odd or eccentric but seems otherwise lucid and organized. Nevertheless, one must resist the temptation to treat the individual as one would someone functioning at a higher level of ego development or run the risk of precipitating a decompensation in the individual's level of adaptive functioning.' In psychotically organized individuals who are more obviously fully impaired, treatment often requires more active and invasive procedures, along with a level of case management. Those who are partially impaired require a focus on reinstating and reinforcing defensive functioning, lest they become overwhelmed by primary process material and further disorganized. It may be necessary to instigate environmental manipulation, such as encouraging changes in work or home environment. The therapist must take an active role in decision making and problem solving and must be willing to be disclosing of one's own thoughts or feelings so as to preclude the development of a transference heavily based in the patient's fantasy life. Medication is often indicated to promote stabilization. Finally, for individuals who are psychotically organized and fully impaired, the initial treatment approach will require a high degree of pacification in regards to primary process material and assistance in stabilization. This approach frequently requires the use of medication and hospitalization, with pacification and support being provided through the hospital milieu, which in addition provides a measure of safety. Once the individual has stabilized, treatment should follow the approach used for treating partially impaired psychotically organized individuals. The above has been an endeavor to articulate a strategy for conceptualizing psychopathology to ensure appropriate treatment interventions. We attempted to describe psychopathology as a function of two primary dimensions and two augmentative variables designed to assist the practitioner in using the appropriate treatment for various individual psychopathologies. This is not intended to provide an exhaustive method for use with all patients. We acknowledge that this is but an example of how psychopathology may be conceptualized from within one particular paradigm, and comparable models can be used by individuals practicing from other comprehensive frameworks of psychopathology. Particularly in this 1 In years past, when clinical decisions were not dictated by business practices, one would likely have sought psychological testing to help in the differential diagnosis of individuals who were suspected of having severely compromised ego development despite showing no obvious signs of psychotic symptomatology. 358 TRIMBOLI AND FARR era when clinicians are faced with encumbrances of arbitrary limitations imposed by cost containment plans and thus are not free to practice in such a way that allows for a thorough evaluation of their patients, conceptualizations such as these will hopefully ensure more efficient treatment practices by guiding appropriate clinical interventions. References Abraham, K. (1924). A short study of the development of the libido, viewed in light of mental disorders. In D. Bryan & A. Strachey (Trans.), Selected papers on psychoanalysis (pp. 418-501). London: Hogarth Press. Bellak, L. (1992). Handbook of intensive brief and emergency psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Larchmont, NY: C.P.S., Inc. Blanck, G., & Blanck, R. (1974). Ego psychology: Theory and practice. New York: Columbia University Press. Butcher, J. M. (1997). Introduction to the special section on assessment in psychological treatment: A necessary step for effective intervention. Psychological Assessment, 9,331-333. Easser, B. R., & Lesser, S. R. (1965). Hysterical personality: A re-evaluation. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 34, 390-415. Fenichel, O. (1945). The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis. New York: Norton. Freud, S. (1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works ofSigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 124-245). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1905) Freud, S. (1957). Instincts and their vicissitudes. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 109-140). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1915). Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, pp. 1-66). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923). Freud, S. (1962a). On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description "anxiety neurosis." In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 3, pp. 85-115). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1895). Freud, S. (1962b). Sexuality in the aetiology of the neuroses. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works ofSigmund Freud (Vol. 3, pp. 259-285). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1898). Friedman, L. (1988). The anatomy of psychotherapy. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. Giovacchini, P. L. (1987). A narrative textbook of psychoanalysis. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson. Greenson, R. R. (1967). The technique and practice of psychoanalysis. New York: International Universities Press. Hartmann, H. (1958). Ego psychology & the problem of adaptation. New York: International Universities Press. Hartmann, H. (1964). Essays on ego psychology: Selected problems in psychoanalytic theory. New York: International Universities Press. PSYCHODYNAMIC GUIDE 359 Hollender, M., & Hirsch, S. (1964). Hysterical psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 120, 1066-1074. Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson. Kernberg, O. F. (1976). Object relations theory and clinical psychoanalysis. New York: JasonAronson. Kernberg, O. F. (1980). Internal world and external reality. New York: Jason Aronson. Kernberg, O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self: As systematic approach to the psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders. New York: International Universities Press. Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press. Kohut, H., & Wolf, E. S. (1978). The disorders of the self and their treatment: An outline. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 59, 413^24. Langs, R. (1978). The listening process. New York: Jason Aronson. Langs, R. (1979). The therapeutic environment. New York: Jason Aronson. Langs, R. (1980). Interactions. New York: Jason Aronson. Langs, R. (Ed.). (1981a). Classics in psychoanalytic technique. New York: Jason Aronson. Langs, R. (1981b). Resistances and interventions. New York: Jason Aronson. Lerner, P. (1991). Psychoanalytic theory and the Rorschach. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. Me Williams, N. (1994). Psychoanalytic diagnosis. New York: The Guilford Press. Paul, I. H. (1973). Letters to Simon. Madison, CT: International Universities Press. Paul, I. H. (1997). Letters from Simon. Madison, CT: International Universities Press. Puryear, D. A. (1979). Helping people in crisis: A practical, family-oriented approach to effective crisis intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Reich, W. (1972). Character analysis. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. (Original work published 1933). Ricoeur.P. (1970). Freud and philosophy: An essay on interpretation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Sandier, J., & Rosenblatt, B. (1962). The concept of the representational world. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 17, 128-145. Schaffer, R. (1976). A new language for psychoanalysis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Shapiro, D. (1965). Neurotic styles. New York: Basic Books. Smith, E. K. (1978). Reassessing a model of assessment. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 42, 423-432. Tyson, P., & Tyson, R. L. (1990). Psychoanalytic theories of development. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Zetzel, E. R. (1968). The so-called good hysteric. International Journal of Psycho Analysis, 49, 256-260.