Summary of an Analysis of Gender Pay Equity of Full

advertisement

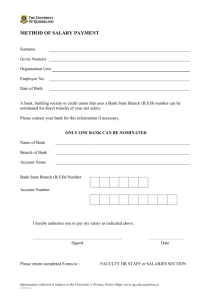

Summary of an Analysis of Gender Pay Equity of Full-Time Faculty Members The Office of Institutional Research and Analysis (IRA) at the request of David Wilkinson, Provost and Vice-President (Academic), has conducted a study to investigate whether there is a gender equity difference in salaries of full-time faculty members at McMaster University. Faculty salary differences may be a result of differences in pay-determining characteristics of male and female faculty. Pay-determining characteristics may be related to occupational characteristics, such as, professorial rank and type of appointment; and individual characteristics, such as years of experience, quality of work and recognition, and subject area knowledge and expertise. This study is conducted for administrative purposes using readily available, existing university data to determine whether pay differences, if any, arise because of gender, after compensating for pay-determining characteristics, at McMaster University. Methodology Over the last decade, numerous analyses concerning gender pay equity have been conducted including studies at the University of Western Ontario in 2005 and more recently in 2010 at the University of British Columbia. Given that these studies relate to Canadian universities, they heavily inform our study in terms of methodology and the selection of independent variables for regression modeling. Table 1 indicates the variables included in the dataset used in this study. Table 1: Dataset Variables Variable Description Primary Dependent variable (response): Annual salary. Not reduced by sabbatical or other leaves. Excludes Annual Salary stipends. Primary Independent variable (predictor): Gender Male=0, Female=1 Secondary Independent variable (predictor): Rank Full, Associate, Assistant, Lecturer Appointment Stream Faculty Age Years in Rank Years at McMaster Years since first degree Years since highest degree Highest degree Prior university experience Canada Research Chair Office of Institutional Research and Analysis Tenure, Special, Teaching, CLA Faculty individual staff member belongs to Age as of Oct 1st 2012 Years since staff member attained their current rank Years of experience at University in a full-time continuing position Years since completing first degree Years since completing highest degree Highest degree earned No=0, Yes=1 No=0, Yes=1 Page 1 This study is based on data extracted primarily from the McMaster University’s Human Resources data system, MacVIP, and supplemented with data from ATP. The sample is limited to full-time faculty as of October 1, 2012 and does not include clinicians because their total earnings are not available from the data sources. At McMaster University, as of October 1, 2012, there were 939 full-time faculty members (excluding clinicians): 354 full professors, 318 associate professors, 248 assistant professors and 19 lecturers. Female faculty members account for almost 36 percent of the total faculty population. The majority of the male faculty are full professors (45%) and associate professors (32%), while female faculty members are mainly associate (38%) and assistant professors (36%). On average, male faculty members are paid higher than female faculty members. The overall average female to male salary difference is $14,503. By rank, on average, male faculty members are paid higher than female faculty in the full ($5,772), associate professorial ($5,792) ranks, and in the lecturer rank ($11,985). On the other hand, on average, female faculty members are paid higher than male in the assistant professorial rank. The average salary of female assistant professors is $2,664 higher than the average salary of male assistant professors. The tenure appointments comprise about 75 percent of the full-time faculty population. Within this group, 493 or 70 percent of the 705 tenure full-time faculty are male, and of these, 264 or 54 percent are full professors. Among the female tenure appointments, the largest group is in the associate professor rank (94 of 212 or 44%). Male faculty members are in general older compared to female faculty and have a higher number of years in rank, years since highest degree and years since first degree. In contrast, the reverse is true for faculty members in the assistant professor rank, and female assistant professors also have a higher average salary compared to their male peers. Two analytical approaches are used in this study: multiple linear regression and the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition methodology. Multiple Linear Regression A simple t-test indicates that there is a difference in the mean salary of male and female faculty members at McMaster University. However, the question in this study is whether the differential salary is related to gender. This difference may be explained by different levels of pay-determining characteristics of male and female faculty members. By modelling the relationship between salary (the dependent variable) and other independent variables, using regression analysis, one can estimate how the mean salary changes with the independent variables such as Gender, Years in Rank, Highest Degree, etc. A multiple regression model is built to determine whether gender played a significant role in determining salary level. The Null hypothesis is that there is no statistically significant relationship between full-time faculty annual salary and gender. If the Null hypothesis is rejected, one could conclude that faculty annual salary is dependent on gender. The conventional criterion used for statistical testing is α equal to 0.01, 0.05, and 0.10 (or 1%, 5%, and 10% significance level respectively). In order to avoid multicollinearity, the variables Age, Years since First Degree, Years since Highest Degree, and Years at McMaster were removed from the model and only Years in Rank is kept as the primary measure for academic experience. To reduce the number of insignificant variables, the Forward, Backward, and Stepwise Selection methods are employed. All four models explained over 74 percent of the variance and the difference between their adjusted R-square is very small. In all four models, the independent variable, Gender, was found to be statistically insignificant at the 5% significance level. However, Gender remains in the model because it is the primary independent variable and it is statistically significant at the 10% significance level. Office of Institutional Research and Analysis Page 2 The final model is the Backward/Stepwise selection model. Its adjusted R-square of 0.7408 indicates that the model can explain 74 percent of the variation. All the variables have a VIF of less than 5 therefore indicating limited multicollinearity. The analysis shows that the average salary of female faculty members is about $2,350 lower than male faculty members at McMaster University after controlling for all other statistically significant predictors of annual salary that were available for analysis. An independent variable is deemed statistically significant if it has a p-value less than the conventional significance levels of 0.01, 0.05, or 0.1. Technically speaking, the p-value of the gender variable at 0.07, is not statistically significant at the 5% level (see Table 7). In other words, there is insufficient evidence to reject the Null hypothesis and conclude that there is a relationship between gender and annual salary of full-time faculty members. However, at the 10% significance level, there is sufficient evidence to reject the Null hypothesis. The results indicate that the average annual salary of full-time faculty members at McMaster is influenced by a number of statistically significant factors, namely: the Canada Research Chair status 1, Years in Rank, Highest Degree Earned, Faculty, Appointment Stream, and Rank. The average annual salary of a faculty member who is a Canada Research Chair is estimated to be about $17,300 higher than one who is not. With respect to Years in Rank, for every year increase, the average annual salary is estimated to increase by about $1,150. The Blinder-Oaxaca Decomposition This study also employs another popular methodology proposed by Blinder (1973) and Oaxaca (1973) that is often used to analyse salary gaps by gender or race. The decomposition technique studies the mean differences between two groups in a counterfactual manner. When used to study salary differences, it divides the salary differential between two groups into a part that is “explained” by group differences in pay determining characteristics, such as education level or years of highest degree, and a residual part that cannot be accounted for by such differences in salary determinants. The “unexplained” part is often used as a measure for discrimination, but it also subsumes the effects of group differences in unobserved independent variables (see Jann, 2008). The result of the pooled two-fold decomposition shows that there is an average difference of about $14,500 in favour of male faculty. Over 84% ($12,200) of the difference can be explained by the pay-determining characteristics identified through the regression methodology, namely Canada Research Chair, Highest Degree, Years in Rank, Department average, Faculty, Appointment Stream, and Rank. The remaining 16% ($2,350) of the difference is said to be the gender pay gap. As its associated p-value (0.06) is higher than 0.05, this unexplained difference is deemed to be statistically insignificant at the 5% significant level. This finding is consistent with the regression analysis finding. Conclusion The analyses suggest that there is a salary differential of about $2,350 in favour of male faculty. At the 5 percent significance level, the margin of error is ±$2,524 (-179 ≤ x ≤ 4,869). If gender is found to be statistically significant as a predictor of annual salary, then the observed pay difference between male and female full-time faculty could be due to gender. The results from the regression and decomposition analyses both suggest that at the 5 percent significance level, there is insufficient evidence to reject the Null hypothesis. Accordingly, there is not enough evidence to support a conclusion that the observed pay difference between male and female full-time faculty is due to gender. However, given that the conventional significance level range is between 0.01 and 0.1, our p-value of 0.07 1 Further analysis w as conducted using the sample but w ithout CRC faculty. The results show strong evidence that there is no relationship betw een gender and the annual salary of non-CRC full-time faculty. Office of Institutional Research and Analysis Page 3 indicates evidence of significance, although that evidence is not strong. Note that our models account for about 74 percent of the variation in salaries. Twenty-six percent of the salary variation between male and female faculty members remains unaccounted for implying that there are further dimensions to salary determination that could be investigated. Further Analysis Gender equity is a high social interest area with complexities that require deep research and analysis. One limitation of this analysis is that it is limited to readily available existing data. It is noted that it may be possible that a couple of the dependent variables (e.g. CRC status and rank) in the model, assumed to be gender neutral, could have gender dependencies and hence could have an effect on the resulting value of the annual salary differential between male and female full-time faculty members. It is suggested that future analysis might specifically determine whether these variables have gender dependencies. Depending on the availability of data, further analysis might take into account personal characteristics such as marital status, number of children, and leave status (e.g. parental). This study is also based on a one-year snapshot dataset and focuses on gender pay equity at the institutional level. Further studies could include longitudinal analysis focused on merit pay increment or tenure progression processes, quality of workrelated-variables, and gender pay equity among faculty members within each Faculty or by professorial rank. Other studies might include analysis of pay differences by wage distribution. Office of Institutional Research and Analysis Page 4