- Design Studio

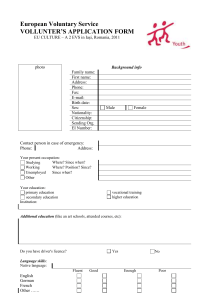

advertisement