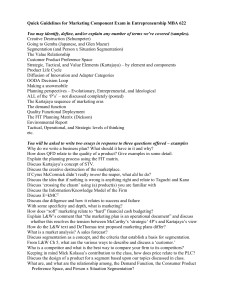

file

advertisement