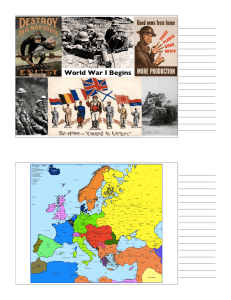

alliances and networks

advertisement