TCF Complaints Management Discussion Document

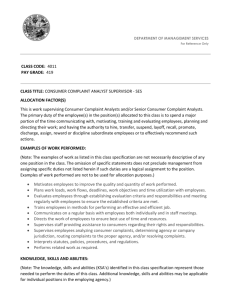

advertisement