Examining well-being, anxiety, and self

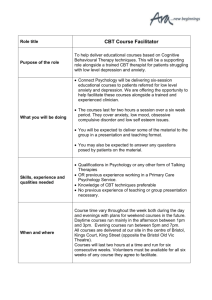

advertisement