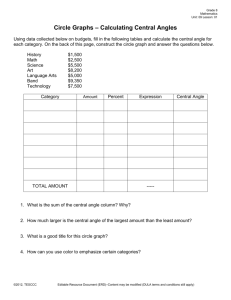

Informational Writing: Feature Article

advertisement