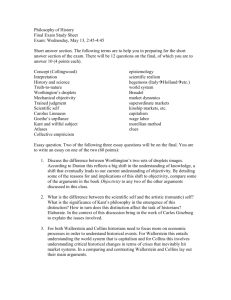

Observation in Teaching: Toward a Practice of Objectivity

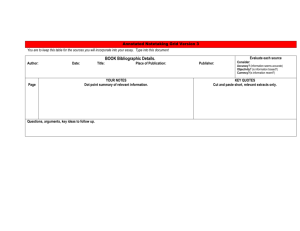

advertisement