HSE - Noise Exposure Monitoring in Malaysia The Factories and

advertisement

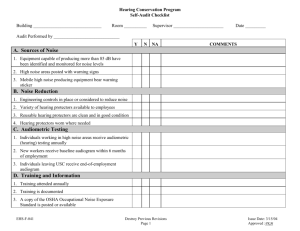

HSE - Noise Exposure Monitoring in Malaysia The Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (Noise Regulations) 1989 in Malaysia requires that noise exposure assessments and monitoring are carried out. This paper discusses the importance of giving due consideration to health and safety earlier in the design chain for noise and the trend in results from installations offshore. Standards for the measurement of noise sources are summarised, as well as the comfort and amenity levels that could be implemented in design stage. A proposal for the role that technology can play in the future of noise exposure monitoring is also discussed. A t e c h n o l o g y RAMS Feature continuous supply of energy, products, consumables and commodities benefits our modern lifestyle: personal transport; industrialisation; heating and cooling. The average power demands in Malaysia from 1990 to 1999 and from 2000 to 2009 increased by a factor of about 2.5. Industrial energy demand increased at a faster rate than the demand by Malaysia as a whole. The increasing number of power station developments by the fastest growing consumer of energy, the industrial sector, is driven by this need for energy and oil and gas. Nearly 40% of Malaysia’s total revenue derived from petroleum resources. All developments pose a similar challenge: to achieve a balance between operational performance and minimizing any adverse impact to the health and safety of employees. One of the many aspects of the occupational health and safety process associated with the energy production and industrial sector is the assessment of noise exposure. Noise exposure is normally taken into account during the Front End Engineering Design (FEED) stages in order to gauge and prevent any potential problems during both construction and operational stages. However, ensuring noise exposure impacts are controlled during the FEED stages is secondary to achieving operational requirements, due to the fast track nature of energy and oil and gas related projects and the correlation between the growth of oil and gas industry and economic performance. Methods to predict the expected noise exposure 70 and evaluate operational noise exposure are listed in a comprehensive set of international standards such as ISO. Usually, a client will explicitly require assessments to be carried out according to those standards. However, alternative criteria have been sought in many countries to step away from conventional international harmonising procedures in order to seek a compliance and assessment tool that reflects the national context due to the political will informed by economic and sociological factors. Malaysia’s Factories and Machinery Act 1967 (Noise Regulations) 1989 The noise regulations are enforced by Malaysia’s Department of Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Human Resources and require that employers carry out noise exposure assessments. The current parameters and criteria for Malaysia are presented in Table 1 along with examples of the legislation in various countries in order to enable a comparison of the approaches. Data for 30 countries was analysed to identify common criteria. The results are presented in Figure 1. Figure 1. A comparison of jurisdictions with harmonised international criteria to those with differing criteria november/december 2013 Visit our website at www.safan.com From Figure 1, it is obvious that the number of jurisdictions that have harmonised their criteria is roughly equal to the number of jurisdictions that have implemented their own criteria. Malaysia is yet to implement the 3 dB exchange rate and 85 dB(A) exposure criteria over 8 hours. The regulations are considered by many to be outdated and not representative of current best practice. Consequently many companies define corporate standards for noise exposure assessments that are harmonised with. An update to Malaysia’s noise exposure regulations is expected in 2014. The update to the occupational health and safety requirements for noise shall comprise changes to the exchange rate and noise exposure criteria. This will bring it generally in accordance with the recommendations made in, which concludes by stating the importance of harmonising noise exposure criteria internationally. As Malaysia progresses towards becoming a developed nation by the year 2020, the economic and sociological factors which formerly acted as a barrier against adopting the criteria recommended by reduce in significance. Also, it is noted in that noise is a demonstrably useful marker of status and class. Overall it is expected that Malaysia’s progress towards a developed nation will be in parallel with a higher awareness on the importance of noise within the workplace, and, the adoption of criteria that are harmonised internationally. There are a number of unresolved ambiguities in the existing noise regulations of Malaysia mainly related to the physical definition of parameters for measurement. For instance, the following are not defined: the weighting network (A, C or Z) to be used for the measurement of the peak noise level; the definition of noise; the technical references and standards to be followed for the measurement of noise exposure and area noise levels; and the scope of industrial application of the noise exposure criteria. These unresolved ambiguities can imply differences of more than 5 dB in measurement of peak noise levels between one of the A-, C- or Z-weighting filters. The definition used in the existing noise regulations is, “Noise level means sound level”. This definition makes no reference to the health and safety aspect of the noise to be considered. Therefore the proposed definition is, “Noise is a sound pressure level that has the potential to cause damage to hearing”. The regulations require that the technician carrying out the noise exposure assessment apply a measurement methodology provided by NIOSH Malaysia. However the methodology does not guide the technician to a set of detailed technical references or standards to be followed in all scenarios likely to be encountered on a range of sites. The scope of application of the noise exposure regulations are expected to include workers at entertainment venues, where, for example, reproduced sound levels can exceed 100 dB(A) by design intent. The Importance of Giving Due Consideration to Noise Earlier In the Design Front-End Engineering Design (FEED) is the process of conceptual development of offshore projects november/december 2013 71 and involves developing sufficient strategic information with which owners can address risk and make decisions. In it is asserted that, “owners with high Front End Planning usage on average spend 8% less than those with low usage”. This cost saving is significant when considered over the lifetime of an installation. The importance of controlling an adverse noise impact at source is recognised as the best approach from a geometrical and temporal perspective and requires the consideration of noise emissions and noise exposure impacts as early in the design chain as possible. From an engineering perspective, there is more flexibility in the implementation of noise control measures during the design phase compared to the ‘as built’ scenario. During FEED options can be assessed without the restraints of a physical built environment on any noise control options. Even a combination of noise control measures may not be enough to attenuate noise emissions and noise exposure levels to comply with criteria. An example combination to attenuate noise would be by implementing measures to the propagation path and to complement that with personal hearing protection. The combination could be assessed at design stage to allow informed decisions to be made on the feasibility of implementing further measures to reduce the noise level. Whereas in the as built and operational scenario it is often not the case that true control of noise at source can be implemented. In specific recommendations related to design were made and summarised as follows: 1. At the design stage of any new installation, consideration should be given to sound and vibration isolation between noisier and quieter areas of activity. 2. The purchase specifications for all new and replacement machinery should contain clauses specifying the maximum emission sound power level and emission sound pressure level at the operator’s position when the machinery is operating. The first point has been discussed. Point 2 relies upon the implementation of machinery purchase specifications that would have been formed from the results of a design assessment for noise. RAMS Feature 72 november/december 2013 Table 2 Notes: a Walkways. In-module walkways/access ways (e.g. between skids): a limit equivalent to the adjacent area applies, provided acceptable PA system audibility is maintained. b Laydown area. In-module laydown area: allow noise limit maximum 80 dB(A) provided that in-module laydown area is not the main laydown area. c The highest permissible noise limit, 110 dB(A), should only be allowed in connection with brief inspections or work tasks that are to be carried out in an area where there is no passage through to other areas. Provisions should be made for noise deflection of noisy equipment when maintenance or other work is carried out in the area. d 85 dB(A) is preferred in order to ensure that the individual employee’s maximum exposure to noise during a 12 hour working day is 83 dB(A). Where the lower limit is not feasible, a maximum area noise level limit of 90 dB(A) shall apply. e For mobile offshore installations, the noise requirement during operations is 5 dB(A) higher than the one given in the table. f For crane cabins, the requirement refers to the equivalent sound level to which the crane driver is exposed during a time period defined by a typical crane cyclus. g For rooms dedicated to coarse pot and pan washers that are unattended when operating, a limit of 84 dB(A) can be applied. h Intermittently manned and normally unmanned offices in work areas can allow 55 dB(A). Visit our website at www.safan.com Comfort and Amenity Criteria for Installations Malaysia Offshore There are no Malaysian regulations that provide acceptable noise levels within offshore accommodation areas. Comfort and amenity criteria take into account various international standards and are deemed to preserve their general principles. The criteria presented below are from and are considered to be suitable for offshore Malaysia. International Standards for the Measurement of Noise In noise exposure assessments, the data acquisition tools, methodology and recordkeeping can vary with the context of the noise level measurement in terms of its location. For example, whether a noise level measurement is to be performed at a location offshore, on board a ship, at an industrial plant or along a factory production line can involve different approaches, which are usefully provided for in international standards and guidelines. International standards for noise measurement instrumentation that should be complied with are in the references. The standards should be listed as the required technical reference by noise exposure monitoring regulations for both manufacturers of the noise measurement equipment and for practitioners of the regulations. Standards to measure noise emitted by equipment and machinery at workplaces as well as for the measurement and assessment of noise exposure are in references16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21. Strategies and case studies for the monitoring of noise exposure are available in [6] and good practices presented in [22]. Additional standards exist for specific machinery. Technology and the Future of Noise Exposure Monitoring In Malaysia Employers are required to control the noise exposure impact by engineering methods if above the action level and it is feasible to do so. However, observations show that compliance with these regulations varies between oil and gas operators and individual assets. We believe it is possible to realise the development of an inspection tool to be used as a benchmark for occupational health and safety and in- RAMS Feature 74 november/december 2013 dustrial hygiene inspectors, Malaysia’s DOSH registered noise competent technicians, and those with responsibilities for dealing with offshore noise compliance issues. Currently, the control of noise is primarily through the means of personal hearing protection. With the inspection tool, connected to a centralised database, it would be possible to determine whether the employee noise exposure level or the absolute area noise level on an offshore installation are high in comparison with the industry benchmark. Stakeholders, owners and operators may also find the technology useful as part of their review of noise exposure monitoring assessments, and, the decision making process for the control of noise risks as well as the veracity of reported measured data. To develop the technology it would be necessary to establish the industry norm for Malaysia offshore. This could be carried out by a review of the available literature and reports, supplemented by site visits to a sample of installations. The data required would be split into the following main categories: • Area noise levels. • This data would detail the noise level of the functional modules on board offshore installations. • Personal noise exposure levels. • This data would detail the noise level of the various trades on board offshore installations. • Average offshore installation noise exposure level. This data would present the results of the data analysed by installation type. The data, once collated for the above categories, may then be processed into a suitable manner of presentation in order to assist the end user. A box and whisker plot would be most suitable to assist in the presentation to Client and stakeholders of the decision making process. The second and third quartiles together with the outliers would be calculated based on the data for the main categories. Software would then compare the level of the measured noise level and propose a decision based on its position in the data range. An example is presented in Figure 2 for illustration purposes only. The red line indicates the Visit our website at www.safan.com measured noise level at pipedeck for an installation offshore Malaysia. The box and whisker plots indicate the data range and decision making outlined in Table 3. From Figure 2 the measured level falls in the third quartile, therefore the recommendation is to consider reducing the noise exposure levels. Similarly, the same analysis process and decision making could be carried out for personnel by job title. In the example, should the recommendations have been made in line with the current noise regulations of Malaysia, it would have been stated, among other recommendations, that: engineering control measures would need to be considered; hearing protection device assessment would have to be carried out; and audiometric testing annually for those employees with pipedeck noise exposure the dominant contribution to their personal noise exposure level. This decision making tool is that it enables insight into the measured noise levels of all noise exposure assessments: The recommendation would acknowledge that for the offshore industry of Malaysia as a whole, the measured area noise level would not be cause for immediate concern and reducing the noise level should be a consideration only. Noise Results From Installations Malaysia Offshore A total of five offshore installations were used to compile the results presented here. The installations are categorised as the following: • One (1) Drilling rig • Two (2) Central processing platforms • One (1) Well head platform A list of noise concerns has been compiled and is presented below: • High pressure gas flow – HP Flare Drum • Fire water pumps, crude oil transfer pumps • HVAC equipment generated noise • Helideck during activities • Crane cabin • Compressors • Significant production capacity increase • Exposure experienced by Operations / Production / Maintenance technicians • Exposure experienced by Crane operators • Exposure experienced by Compressor technician • Exposure experienced by E&I personnel • Exposure experienced by Central Control Room personnel. november/december 2013 75 Noise data has been grouped into a limited number of categories and some of the categories may not exhibit complete homogeneity. From the above plot, the average exposures on a drilling rig are similar to those on a production platform. Also, the average exposure on a well head platform is expected to be approximately half that likely to be experienced on a drilling rig or production platform. From the above plot, production personnel have a slightly lower risk than operations and maintenance. Also, the upper quartile of operations personnel is higher than that for maintenance. This suggests that some operations personnel actually experience higher noise levels than maintenance technicians. This approach allows for the risk of noise exposure to be determined. It acts as a useful decision making tool for the purposes of compliance assessments, additional noise exposure monitoring work and for the proposal of noise attenuation measures. Further work We believe that the technological tool for noise exposure assessments has great potential in solving many of the problems related to the outcomes of noise exposure measurement results. At the same time, we are aware that there are several issues to be improved such as: • The relatively small data sample available for this paper. Collaboration with stakeholders would ensure more and better data sets. • Automation of the technological tool with a graphic user interface to enable a seamless experience for users. • Removing the manual data entry method. The use of intrinsically safe touch screen devices would be a time saving procedure for analysis of personal noise exposure and area measurements. Conclusions Acknowledgements A review of Malaysia’s noise regulations has been carried out with Malaysia’s approach compared to international norms, and, ambiguities have been identified with alternatives suggested to resolve those points. It is expected that Malaysia will move towards greater harmony with international standards. A review of material on the importance of placing emphasis on the design stage has identified that an 8% reduction in spending is likely over the lifespan of an installation. Criteria to pre- RAMS Feature serve the comfort and amenity of installations offshore have been identified and presented. Internationally accepted standards for the measurement of noise have been put forward. A proposal for the role of technology and the future of noise exposure monitoring in Malaysia has been made in the form of a decision making tool that would assist owners in finding the balance between operational requirements and health and safety concerns. Finally, the main drawback of using the technological tool proposed is that it requires collaboration with a number of stakeholders responsible for enforcement of health and safety and regulation of the oil and gas industry in Malaysia. Therefore its potential will only be realised by close collaboration and engagement with stakeholders. 76 november/december 2013 The author would like to extend his gratitude to Gary Strong and their peers and colleagues at the Malaysian Industrial Hygiene Association and Bureau Veritas Malaysia Sdn Bhd for their support and introduction to the world of occupational health and safety. References 1. Factories and Machinery Act 1967 [Act 139] P.U.(A) 1/89 Factories and Machinery (Noise Exposure) Regulations 1989 InVisit our website at www.safan.com corporating latest amendments – P.U.(A) 106/89, 1989. 2. Abd Rahim N., Md. Hasanuzzaman, “Energy Situation in Malaysia: Present and Its Future”, Country Report, Sustainable Future Energy 2012 and 10th Sustainable Energy and Environment Forum, Brunei Darussalam (November 2012). 3. Take 5 Oil and gas, Volume 1 – Issue 2 – 5 June 2013, Ernst & Young. 4. Publication 97-1, “Technical Assessment of Upper Limits on Noise in the Workplace,” International Institute of Noise Control Engineering (December 1997). 5. w w w . d o s h . g o v . m y _ i n d e x . p h p _ option=com_content&view=articl.pdf accessed 12:10 hours, 22nd October 2013. 6. Hansen C. H., Goelzer B., Schmidt G. A., “Occupational Exposure to Noise: Evaluation, Prevention and Control”. Special Report – S 64, World Health Organisation. 7. The Unwanted Sound of Everything We Want: A Book About Noise, Public Affairs (March 2012). 8. CII Best Practices Guide, “Improving Project Performance”, Ver. 4, page 17, Construction Industry Institute (2012). 9. NORSOK Standard S-002 Rev.4 Working Environment (2004). 10.IEC 61672-1 Electroacoustics – Sound level meters – Part 1: Specifications. 11.IEC 61672-2 Electroacoustics – Sound level meters – Part 2: Pattern evaluation tests. 12.IEC 61672-3 Electroacoustics – Sound level meters – Part 3: Periodic tests. 13.IEC 61260 Electroacoustics – Octave-band and fractional-octave-band filters. 14.IEC 61252 Electroacoustics – Specifications for personal sound exposure meters. 15.IEC 60942 Electroacoustics – Sound calibrators. 16.I SO 11201 Acoustics – Noise emitted by machinery and equipment – Determination of emission sound pressure levels at a work station and at other specified positions in an essentially free field over a reflecting plant with negligible environmental corrections. 17.ISO 11202 Acoustics – Noise emitted by machinery and equipment – Determination of emission sound pressure levels at a work station and at other specified positions applying approximate environmental corrections. 18.ISO 11202 Acoustics – Noise emitted by machinery and equipment – Determination of emission sound pressure levels at a work station and at other specified positions applying accurate environmental corrections. 19.ISO 9612 Acoustics – Determination of occupational noise exposure – Engineering method. 20.ISO 1999 Acoustics – Estimation of noiseinduced hearing loss. 21.ISO 2923 Acoustics – Measurement of noise on board vessels. 22.G ood Practice Guide for Strategic Noise Mapping and the Production of Associated Data on Noise Exposure, European Commission Working Group Assessment of Exposure to Noise (WG-AEN) (January 2006). 23.Noise Exposure and Control in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry, Health & Safety ExPET ecutive, UK. This publication thanks Eyad Hasbullah, Senior Acoustics & Vibration Consultant, Bureau Veritas (M) Sdn Bhd, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for providing this paper which was presented at the 7th RAMS Asia Conference and Exhibition held in Kuala Lumpur on the 23rd – 24th September 2013. 11/12-03 ENQUIRY NUMBER: Have you read our other magazine? see us on the web at http://www.safan.com november/december 2013 77