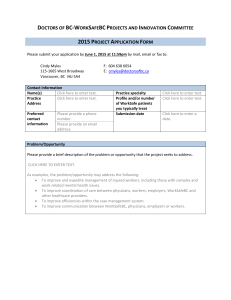

Untitled - Ministry of Labour - Province of British Columbia

advertisement