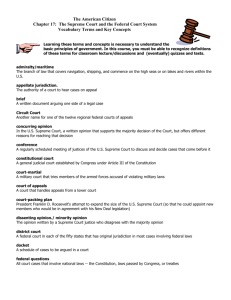

the supreme court, habeas corpus, and the war on terror

advertisement