Provision of Public Goods and Violent Conflict: Evidence from

advertisement

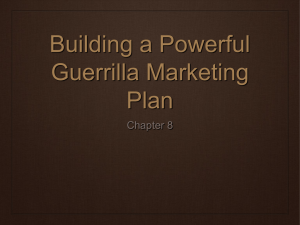

Provision of Public Goods and Violent Conflict: Evidence from Colombia∗ Darwin Cortés† Daniel Montolio ‡ October 20, 2013 Abstract: The Colombian conflict has lasted for around 50 years. It has been fueled by the financial opportunities coming from production and traffic of illegal drugs, and predation of other natural resources. In such a context it is not clear what policies are more effective to reduce conflict. Two public policies that are frequently mentioned as effective to reduce conflict are investments in roads and education. However, a priori, both investments in roads and education may either increase or reduce conflict. After controlling for possible problems of endogeneity, we show that increases in roads provision reduces conflict while education does not. Because this is robust to controlling for measures of state capacity and governance, and the opportunity cost of conflict, our results are likely to be explained by the relative mobility of education and roads. Policies that increase roads provision might help to fight against the intensity of conflict. JEL codes: D74, H41 Keywords: Conflict, Road Density, Education. ∗ We thank two anonymous referees and the editor, Juan Fernando Vargas, for very detailed comments and insights to previous versions of this paper. We are also grateful to Dario Maldonado for his comments. Usual disclaimer applies. We also thank Daniel Martı́nez and Alejandro Montoya for their research assistance. Daniel Montolio acknowledges support from grant 2009SGR102 from the Catalan Autonomous Government. † Corresponding author, Department of Economics and CeiBA-Complejidad, Universidad del Rosario, Colombia, Calle 12C 4-69, Piso 3, 111711, Bogota, Colombia - darwin.cortes[at]urosario.edu.co ‡ IEB, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain. montolio[at]ub.edu 1 1 Introduction The economic causes of conflicts have received considerable attention in the economic literature. Part of the literature is dedicated to the analysis of income shocks (e.g. Miguel et al., 2004; Dube and Vargas, 2013), with special attention to natural resources (Frankel, 2010). In the Colombian case, it is well known that irregular armies (paramilitaries and guerrilla) seek rents by predating on coca production (Angrist and Kugler, 2008), oil revenues (Dube and Vargas, 2013), and other similar resources. Although the role of the provision of public goods in conflicts has been studied both theoretically (Scoones, 2013) and in other contexts (e.g. Berman et al., 2011, 2013), whether public good provision mitigates or exacerbates the Colombian conflict is largely unknown. Among policymakers, investments in roads and education are often claimed to be effective to mitigate conflict. It is argued that building roads reduces transportation cost. This in turn reduces cost of raising legal crops increasing opportunity cost of raising coca crops. It may also facilitate the arrival of other institutions and the construction of other public goods, which might improve state capacity and governance and increase the opportunity cost of making war. However, road construction might increase conflict for at least two reasons. First, irregular armies are likely to attack more intensely those regions in which the state intends to make more presence as a way to have more control on those regions or to fight against the enemy. Second, irregular armies may take advantage of roads to make their activities (controlling areas, transporting coca, weapons, fighters, etc.) more easily. Similarly, and depending on its nature, content and delivery, education can either fuel or deter conflict. On the one hand, as Davies (2004) highlights, conflict can be fueled by education through malicious educational policies that, for instance, exclude or humiliate minorities, perform cultural repression, exacerbate class and gender differences or indoctrinate students into hate and revenge. Uneven educational policies across the country, affecting the educational opportunities, can be also a catalyst of violent conflict (Bush and Saltarelli, 2000). On the other hand, there is also long standing evidence regarding education as a mechanism that promotes peace, human rights and the defence and protection of democracy and, hence, preventing conflict (McGlynn, 2009). Moreover, apart from the social component (or public good component) of education, individuals with better levels of education are likely to have access to jobs that are better paid. This increases the opportunity cost of making war. The aim of this paper is, hence, to study the effect of the provision of roads and education on conflict. The main results suggest that an increase in road density is likely to reduce conflict, while an increase in quality of education is not. The result on education shows that effective policies to prevent conflict might be not effective when the conflict is already in place. The finding is in line with the fact that households, regardless of their human 2 capital accumulation, might move to other municipalities, leaving regions where conflict is more intense. Migration of households might make education policies less effective as a tool to reduce conflict. The main empirical problem in identifying the effect of the provision of roads and education on conflict is endogeneity. Not only may the provision of public goods affect conflict but also conflict may affect the provision of public goods. To tackle this issue we adopt an instrumental variables (IV) approach. We use historical instruments related to the provision of public goods. To instrument road density we use road density in 1949, a measure that is previous to the foundation of the oldest irregular army that is involved in the contemporaneous Colombian conflict. Finally, to instrument current quality of education we use the average educational attainment of household heads in 1993. As is well known in the literature of economics of education, in every society people’s educational achievement is positively correlated with their parents’ education (Björklund and Salvanes, 2011). The idea is to exploit the variation across municipalities of educational attaintment of household heads in 1993 to instrument the average education quality in the period 2000-2005. There are several theories that might be behind our results. Broadly speaking, those theories relate to governance and state capacity, opportunity cost and gratitude (Berman et al. 2012). The provision of roads and education might improve state capacity and governance by facilitating the construction of other public goods or institutions. It might also increase the opportunity cost of making war or make people more thankful to the government. Since our data is a municipality cross-section, some of these explanations are likely to raise concerns on the credibility of our empirical strategy. For this reason, we introduce as controls three (exogenous) variables that are related to these explanations. We control for presence of institutions and political elections, which are measures of governance and state capacity. We also control for poverty, which can be interpreted as a measure of opportunity cost of conflict (and to some extent of gratitude).1 Our results are robust to these controls. In the Colombian case, the bulk of the studies on the relationship between public goods and conflict concentrate on the consequences of conflict for the provision of public goods. The literature has studied the effect of conflict on social development (Sánchez and Diaz, 2005), education (Barrera and Ibáñez, 2004; Dueñas and Sánchez, 2007; Rodrı́guez and Sánchez, 2009, 2010) and infrastructure (Villegas and Duque, 2009). To the best of our knowledge no study tackles the causal effect of the provision of public goods on conflict in the Colombian case. 1. These variables are not affected by the 2000-2005 conflict since they are measured in 1993 (poverty), 1995 (institutions) and 1997 (election results). In this sense these controls are exogenous to the contemporary conflict. 3 In other contexts, the relationship between public goods and conflict has been studied more extensively. The literature shows that this relationship is complex and evidence is mixed. Some studies show that increases in certain kind of government services reduce violence (Berman et al. 2011). Moreover, reductions of conflict might be associated to improvements in state capacity and governance (Besley and Persson, 2009, 2011). Other papers show that increased economic activity in areas with low presence of the government might increase rent-seeking and predatory behavior (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004 and Berman et al. 2013). The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a brief overview of the Colombian conflict. Section 3 specifies the empirical strategy, paying special attention to the identification of causal relations between the variables of interest. Section 4 describes the data. Section 5 presents the main empirical results. Finally, section 6 concludes and offers some policy implications of the main results. 2 Background on the Colombian Conflict The Colombian conflict has lasted for over fifty years. One of the fighting groups is the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the oldest active guerrilla in the world, founded in 1964. This guerrilla has political roots that can be at least traced back to the period known as La Violencia, which was triggered by the 1948 assassination of populist political leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. La Violencia is a period of civil conflict in the whole country between supporters of the Liberal and Conservative parties. It covers the period 1948-1958. During La Violencia, several members of the Liberal Party organized self-defence groups and guerrilla units in the countryside, which fought against the police and other groups under the control of the Conservative Party. In 1957 both parties signed the pact of Sitges, an agreement between the two parties to alternate the presidential power for 16 years, the so-called Frente Nacional (National Front). In the meantime, during the 50s, there were several attempts to sign peace agreements with the liberal guerrillas. Some of them signed these agreements, other did not. The remaining militants of liberal guerrillas together with some communist militants reorganized themselves into the FARC. This guerrilla movement claims to be fighting for the rights of the poor in Colombia, to protect them from government violence and to redistribute land to the poor. Colombia is a country very rich in oil, gold and coal. The presence of these resources has fueled the conflict for decades.2 In the 1960s Colombia became a producer and exporter of marihuana. Its production and exports rapidly fell down, mainly because of the increased 2. See Dube and Vargas (2013) for empirical evidence on oil and conflict. 4 supply of Californian marihuana. By the end of the 1970s the traffickers began to import coca leaf from Bolivia and Peru. This coca leaf was processed in Colombia into cocaine, that was re-exported to the USA (Diaz ad Sanchez, 2004). The first paramilitary groups were organized in the 1970s, but it was during the 1980s that they scaled-up and became better organized, mainly because large rural landowners and drug traffickers used paramilitaries to defend themselves from guerrilla extortions. However it is only in the 1990s that both phenomena, paramilitaries and illegal crops production, acquired national importance. The paramilitaries scaled up during the 1980s but only developed a national organization in the second part of the 1990s. Coca crops harvested in Colombia experienced a huge increase after the US government eliminated the Amazon air bridge in 1993. Indeed, according to Colombian and international authorities, during the nineties both the guerrilla and the paramilitaries increased their involvement in the drug industry (protection of crop fields and clandestine labs) as reported, for instance, by the Ministry of National Defence of Colombia (2000) and the United States General Accounting Office (1994). For these reasons the Colombian conflict became more complex during the nineties. It has three conflicting groups: the guerrilla trying to overthrow the government and control the state, the government struggling to retain power, and the paramilitary groups fighting against guerrillas, trying to seize the territory under the guerrilla control. Moreover, even if formally the Colombian conflict has three actors, there is evidence showing that the paramilitaries have acted in coordination with the regular army to protect the interests of powerful elites, including multinational companies, large landowners and drug traffickers. Acemoglu et al. (2009) present evidence supporting the fact that paramilitary groups have significant effects on elections. The authors claim that this supports the idea that paramilitaries have a symbiotic relationship with politicians: the irregular army provides votes to politicians with similar preferences concerning the provision of public goods, and politicians implement policies that are close to those preferred by the paramilitaries. 3 Empirical Strategy In order to assess the impact of the provision of roads and education on the Colombian conflict we model both the probability for an irregular army to commit an attack (onset of conflict) and the average number of attacks (intensity of conflict) in the Colombian municipalities. The naive specification for the onset of conflict is: 1l [Ai > 0] = α + θ1 Ri + θ2 Ei + Xi0 δ + ui , 5 (1) . Similarly, for the intensity of conflict we have: Ai = β + θ3 Ri + θ4 Ei + Xi0 γ + νi , (2) In equation (1) the dependent variable, 1l [Ai > 0], is a dummy variable taking value one if municipality i has experienced at least one attack by an irregular army in the period 20002005; and zero otherwise. We use two outcome dummies, one for guerrilla attacks and the other for paramilitary attacks. In Equation (2) the dependent variable, Ai is a continuous (latent) variable with a lower limit.3 We use two outcome variables, yearly average of guerrilla attacks and paramilitary attacks in the period 2000-2005. We use OLS in order to estimate the best linear approximation to the conditional expectation function. Given the nature of our dependent variables, Equation (1) is also estimated using a probit model and Equation (2) is also estimated using a tobit model.4 The results using the probit and tobit models are reported in Appendix A. For both equations variable Ri measures the density of primary and secondary roads (Km of roads/Area) in municipality i, Ei is the average quality of education in municipality i measured by a standardized national test. Vector Xi is a vector of control variables of municipality i, including department fixed effects, size of municipality (average population), geographical controls (longitude, latitude, temperature and rainfall), and welfare and institutional controls (institutions, political elections and poverty). Variables ui and νi are the error terms. The coefficients θj , j = 1, ..., 4, are the coefficients of interest. They capture correlations between our variables of interest and conflict. Estimates of Equations (1) and (2) are very likely to be biased due to endogeneity issues. There might be a reverse causality between the provision of public goods and conflict. Not only may the provision of public goods affect conflict, but conflict may also affect the provision of public goods. For instance, Villegas and Duque (2009) report that part of the violent activity of irregular armies in Colombia is against public infrastructures. Barrera and Ibáñez (2004) provide evidence to show that conflict lowers education enrolment rates for all age groups. The effect is greater for more vulnerable groups like women and youngsters, especially among indigenous people. In addition, there exist various ways, as presented in Novelli (2010) that education (opportunities, actors and institutions) can be negatively affected by violent 3. Since all continuous variables are standardized, the lower limit is not zero anymore. For the outcome A, it is equal to 0−E[A] , where E[·] denotes the mean and V [·] denotes the variance. V [A] 4. The tobit model allows us to estimate the effect for municipalities that already suffer conflict. We do not use a poisson or negative binomial functions which are indicated for count data, because our outcome is the standardized (mean equals to zero and variance equals to one) yearly average of a count variable (attacks of irregular armies), which is a continuous variable. 6 conflict. Aspects such as direct attacks to schools, students or teachers; sexual violence; forced recruitment or occupation of school buildings and the psychological damage of exposure to conflict of the main actors of the educational process. To deal with the endogeneity issues we use an IV approach. We instrument the provision of each of the two public goods mentioned above. To estimate the model we use Two-Stage Least Squares. Formally, Ri = λ + ηIViR + ζIViE + Xi0 ϑ + i Ei = κ + ιIViR + ξIViE + Xi0 ρ + µi (3) b i + θ6 E bi + Outcomei = ϕ + θ5 R Xi0 ϕ + εi , where Outcomei is either 1l [Ai > 0] for the onset of conflict or Ai for the intensity of conflict. Ri is the road density in municipality i, Ei is the quality of education in municipality i, IViR is the instrument for the road density in municipality i and IViE is the instrument for the quality of education in municipality i. The other variables are the same as described previously. Our coefficients of interest are θ5 and θ6 . This captures the causal effect of quality of education and road density on conflict. The first two equations in Equation (3) are bi and E bi , that come from estimated in the first stage. The estimated values of R and E, R the first stage are used in the second stage as regressors. The instrument for road density is the road density in 1949 by municipality. This instrument is a proxy for the historical level of public good provision in each municipality. The provision of public goods is more likely to be improved in those municipalities that have already invested on them. One key advantage of our instrument is that it is previous to the year in which the oldest Colombian guerrilla, the FARC, was founded (1964). The instrument for quality of education is the average years of education of household heads in 1993 by municipality. This instrument is a proxy for the average educational level of the previous generation in each municipality. The literature on economics of education has shown that there exists a positive correlation between the level of parents education and the educational achievement of their children. Since both instruments are historical they are likely to not fulfill the exclusion restriction. Not only might road density in 1949 affect conflict through contemporary road density but also through other variables. For instance, enjoying more road density in 1949 makes more likely for a municipality to have better institutions or less poverty. Similarly, a municipality whose households heads are more (less) educated is more likely to be relatively richer (poorer) 7 than the others. This in turn affects where the irregular armies attack. In order to tackle this issue we directly include a set of variables that might be related to both the provision of public goods and conflict, including some of institutions and poverty. These controls are explained in the next section. Some other caveats to our approach are in order. First, there might be problems of omitted variables. This might occur if, for instance, roads were build in municipalities with a specific (low or high) level of poverty. In this case, the instrument would be related to the outcome through an omitted variable (poverty). To control for this, and the other main explanations provided by the literature, namely, state capacity and governance of conflict, we include controls of political elections, presence of institutions and poverty. A caveat is important in this point. Governance is a concept that is not easy to measure. It has to do with the political process and how politicians are accountable to citizens. However the relationship between governance and elections is complex. On the one hand, the literature on public economics has stressed the relationship between elections and politician performance. Particularly important for us, it has shown that a larger margin of victory in elections might be related to larger taxes because of the large citizens approval of politicians performance (Solé-Ollé, 2003). On the other hand, it might reflect that citizens have been forced to vote for some candidates (Acemoglu, et. al. 2013). Even if it is hard to interpret this relationship it seems that governance is related to election results. We use the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections as a measure of election results.5 Second, we might have problems of weak instruments. To check this we look at the t-statistic of the coefficients of the instruments included in the two first-stage equations in Equation (3). We also look at the F-statistic of the first stage. These regressions are estimated using 2SLS.6 Since our instruments are cross-section data, we collapse the other variables into averages using annual data for the period 2000 - 2005. Using panel data together with cross-section IV could artificially reduce the standard errors of the estimates. The price of using cross-section data is that we cannot introduce municipality fixed effects to sweep out the effect of unobservables at the municipality level. Instead we introduce a complete battery of controls. As mentioned above we include department fixed effects, size controls (population), geographical and climate controls (longitude, latitude, temperature and rainfall), welfare and institutional 5. One of the most common measures of market concentration in the literature of industrial organization is P the concentration ratio. This is the sum of the m-largest firms’ shares in the market, CRm = m s . The i i=1 proportion of votes obtained by the winner can be interpreted as the one-candidate concentration ratio, CR1 . 6. In the Appendix we report results for the probit and tobit models. We use the ML estimator. Since this estimator is very likely not to converge when there are more than one endogenous variable, we only report the results introducing each endogenous variable one by one. Instead we control for the instrument of the endogenous variable that we are not instrumenting. 8 controls (institutions, political elections and poverty) and the level of coca production in 1994. Population size helps to control for the scale of conflict. Geographical controls are fully exogenous and may help to explain some likelihood of conflict, related to strategic zones or strategic corridors for irregular armies. Finally, we standardize7 all the continuous (explained and explanatory) variables to facilitate comparison between the coefficients of interest. 4 Data and Descriptive Statistics As mentioned in the previous section, we build up a unique cross-section database that comes from collapsed panel data for the period 2000-2005, gathered from different sources. Data on the Colombian conflict comes from CERAC, an event-based database at municipality level (1,002 Colombian municipalities). Data on roads and geographic coordinates come from the National Geography Office (IGAC). The measure of the quality of education is a language test score in a national standardized test administrated by the National Office for Education Quality (ICFES). Population size, educational attainment and poverty data (proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs) are from the National Statistics Office (DANE). Population sizes are annual estimations based on population censuses. Educational attainment and poverty variables come from the 1993 population census. Data on temperature and rainfall are from the National Weather Office (IDEAM). Data on the number of institutions per 1,000 inhabitants in 1995 (including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions) come from Fundacion Social, a Jesuit NGO in Colombia. Data on the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997 come from the National Election Office (Registradurı́a Nacional). The variable that measures the level of coca production in 1994 is taken from Diaz and Sanchez (2004). The variable is a categorical variable that takes the following values: 0 (no hectares of coca harvested); 1 (1-100 hectares of coca harvested); 2 (101-1,000 hectares of coca harvested) and 3 (more than 1,000 hectares of coca harvested). In Table 1 we report the main descriptive statistics of the variables used in the empirical estimation. Regarding conflict, a given municipality has a 36% probability of being attacked by the paramilitary and 59% of being attacked by the guerrilla, on average; while the average intensity of conflict, measured by the number of attacks, is higher for the guerrilla (0.63) than for the paramilitary (0.17). In Figure 1 we report the spatial distribution of the onset and intensity of the Colombian conflict for both paramilitaries and the guerrilla. Both groups carry out attacks in practically all of Colombia except for the south, which is covered by the northern part of the Amazon jungle. 7. Mean equals to zero and variance equals to one. 9 Table 1: Descriptive statistics Variable Obs Mean Std. Dev. Min Max Onset of conflict (guerrilla) Onset of conflict (paramilitary) Intensity of conflict (guerrilla attacks) Intensity of conflict (paramilitary attacks) 1,002 1,002 1,002 1,002 0.59 0.36 0.63 0.17 0.49 0.48 1.30 0.41 0 0 0 0 1 1 14.71 4.71 Road density (kms/km2) Education (test score) 1,002 1,002 0.27 46.17 0.54 2.02 0 38.23 8.74 53.76 Population (thousand inhabitants) Temperature Rainfall Area (km2) Longitude Latitude Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 Winner voting in 1997 (%) Coca crops in 1994 1,002 1,002 1,002 1,002 1,002 1,002 948 1,002 934 1,002 41.02 21.35 1,879.01 756.66 -74.71 5.59 1.19 52.04 51.37 0.09 240.23 4.97 1,030.98 1,821.72 1.53 2.46 0.85 18.82 12.69 0.45 1.09 3.90 160.00 17.53 -78.83 -4.19 0 9 12 0 6,725.95 28.90 7,750.00 18,381.05 -67.54 11.74 12.49 100.00 94.17 3 1,002 1,002 0.08 4.67 0.13 1.15 0 0 1.28 8.50 Outcomes Endogenous regressors Controls Instruments Road density in 1949 (kms/km2) Education Attainment in 1993 (years) Regarding road density, Colombian municipalities had an average of 0.27 kilometres of roads per square kilometre in 2001. Again, road density varies widely across municipalities, from zero to 8.74 kilometres of roads per square kilometre. The quality of education (language score) is measured on a scale from 0 to 100. Language score averages 46.17 points across Colombian municipalities. In Figure 2 we depict the distribution of these variables on the map of Colombia. Both road density and the quality of education are worse on the periphery of the country. Road density is also bad in Magdalena Medio, and the poorest quality of education is concentrated on both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. Regarding controls, the population size of Colombian municipalities ranges from one thousand to almost seven million, with an average of 41 thousand inhabitants. The average temperature is 21 Celsius degrees and average rainfall is 1,879 millimeters per year. There was an average of one institution per 1,000 inhabitants in 1995, with a maximum of 12 institutions. Around 52.04% of the population was poor in 1993. The average winner voting proportion in mayoral elections in 1997 was of 51.37% with a range that include mayors elected with only 12.0% of the votes up to 94.17% of the votes. 10 Figure 1: Onset and Intensity of conflict The instruments used to tackle the endogeneity problem are depicted in Figure 2. First, in 1949, the municipalities with the smallest quantity of primary and secondary roads were evenly distributed across Colombian Departments. Municipalities with no roads are very often far from their respective department capitals. Second, the educational attainment of heads of households in 1993 was 4.67 years, on average. 5 Main Results In this section we focus on the results obtained for the determinants of both the average number of attacks (intensity of conflict) and the probability of suffering an attack (onset of conflict).8 Recall that all continuous variables have been standardized for the regression analysis in order to facilitate comparison of coefficients. As a baseline set of results in Table 2 we report the estimations of the naive specifications presented in Equation (1) and Equation 8. The tables for both intensity and onset report the results for paramilitaries an guerrilla. We have done all the estimations for the total number of attacks and the total onset of conflict (sum of paramilitaries an guerrilla) obtaining consistent estimates with those reported. These results are available upon request. 11 Figure 2: Main explanatory variables and historical instruments (2). For each measure of conflict (onset and intensity) we report coefficients with the full set of controls and Department fixed effects. The correlation between road density and conflict seems to be negative. It is significant for all measures of conflict except for the onset of paramilitary attacks. Finally, the naive estimations for education show that the correlation between the quality of education and conflict is less robust. In this case the estimated coefficients are more erratic both in magnitude and significance. Estimates of Equation (3) for road density and education quality are reported in Table 3 (intensity of conflict) and Table 4 (onset of conflict). Each of these tables has three panels and six columns. In panel A we report the results for paramilitary attacks. In panel B we report the results for guerrilla attacks. In panel C we report the first stage results. In column (1) we report results with no controls. We progressively add controls in the subsequent columns. In column (2) we report results controlling for the instruments of the other endogenous variable, size and geographical controls (average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature and rainfall), coca crops in 1994, and department fixed effects. In column (3)-(5) we separately control for presence of institutions, poverty incidence and vote proportion of winner in mayoral elections, respectively. In 12 Table 2: Naive estimations VARIABLES Paramilitaries Onset Intensity Guerrilla Onset Intensity Road Density -0.0188 (0.0234) -0.189*** (0.0600) -0.124*** (0.0286) -0.142*** (0.0530) Education Quality 0.0269 (0.0220) 0.0351 (0.0322) 0.00557 (0.0235) 0.0801* (0.0360) X X 885 X X 885 X X 885 X X 885 Other Controls Department FE Observations Note: OLS results for both onset and intensity of conflict. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Included controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall, number of institutions per 1,000 inhabitants in 1995, average education attainment of household heads in 1993, poverty in 1993, winner voting proportion in mayoral elections in 1997 and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. column (6) we report results with all controls.The estimates of θ5 and θ6 are reported in the first two rows of panels A and B. The estimates of η and ξ are reported in the first row and fifth row of panel C, respectively. In the estimations with the full set of control variables (column 6 in Table 3) the results for road density show that a one standard deviation increase (departing from its mean value) of road density causes a 0.56 standard deviation decrease in the number of paramilitary attacks and a 0.22 standard deviation decrease in the number of guerrilla attacks. The effect on paramilitaries attacks is statistically significant. The effect on guerrilla attacks is not. The presence of institutions seems to reduce the number of paramilitary and guerrilla attacks, which support the state capacity story. Other explanations seem to play no role. The results are far less conclusive for quality of education. The estimates of the coefficient of interest for paramilitary attacks are stable in magnitude and sign but are not significant (Panel A, Table 3). The estimates of the effect on guerrilla attacks are not stable in magnitude, sign nor significance (Panel B, same table). Panel C of Table 3 shows that the instrument for roads (road density in 1949) and education quality (education attaintment in 1993) are very significant to explain the endogenous variables. An increase of one standard deviation of road density in 1949 causes an increase of 0.08 standard deviations of road density in the 2000s. An increase of one standard deviation of education attaintment in 1993 causes an increase of 0.17 standard deviations of education quality in the 2000s. All F-stats except one are larger than 10. The results for the onset of conflict are more robust (see Table 4). The results for road 13 Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table 3: Intensity of Conflict - Road Density - Education Quality Road Density Education Quality (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.881*** (0.179) 0.481*** (0.121) -0.481** (0.211) 0.151 (0.153) -0.390* (0.206) 0.210 (0.159) -0.0690*** (0.0243) -0.633** (0.271) 0.254 (0.313) -0.593** (0.237) 0.167 (0.165) -0.0455 (0.0303) -0.564** (0.283) 0.439 (0.340) -0.0619** (0.0300) 0.0210 (0.117) -0.0538* (0.0304) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 -0.0867 (0.107) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density Education Quality (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.808*** (0.178) 0.198** (0.0945) -0.298* (0.179) -0.0582 (0.0887) -0.239 (0.190) -0.00852 (0.0978) -0.0883** (0.0385) -0.378 (0.241) 0.0941 (0.212) -0.329 (0.200) -0.0272 (0.0941) 0.0174 (0.0477) -0.224 (0.267) 0.255 (0.245) -0.109*** (0.0330) 0.0948 (0.115) 0.0160 (0.0497) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.00367 (0.108) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density in 1949 Panel C: First Stages (1) F-test R2 1st stage Education Attainment in 1993 F-test R2 1st stage Observations Other Controls Department FE 0.089*** (0.0288) 41.493*** 0.2246 0.3875*** (0.0309) 82.447*** 0.1678 0.084*** (0.0242) 26.427*** 0.4719 0.3701*** (0.0295) 81.799*** 0.5632 0.091*** (0.0240) 21.953*** 0.5368 0.3586*** (0.0301) 74.468*** 0.5733 0.082*** (0.0275) 17.036*** 0.472 0.179*** (0.0395) 10.365*** 0.5877 0.077*** (0.0273) 25.284*** 0.4773 0.3622*** (0.0307) 72.723*** 0.5596 0.0844*** (0.0243) 13.428*** 0.5506 0.172*** (0.0427) 8.207*** 0.5905 1,002 1002 X X 948 X X 1,002 X X 934 X X 885 X X Note: OLS regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. density show that a one standard deviation increase of road density causes a reduction of 0.28 in the probability of being attacked by paramilitaries and a reduction of 0.41 in the probability of being attacked by the guerrilla. Both effects are significant and robust to different specifications. The presence of institutions seems to reduce the onset of both paramilitary and guerrilla attacks, which support the state capacity story. Notice as well that poverty 14 seems to increase the onset of guerrilla attacks. This is compatible with the opportunitycost-of-conflict explanation. Other explanations seem to play no role. The results are a bit less conclusive for quality of education. The estimates of the coefficient of interest for the onset of both paramilitary and guerrilla attacks are stable in magnitude and (positive) sign but are not always significant (Panels A and B, Table 4). Panel C of Table 4 replicates Panel C of Table 3.9 Furthermore we look at whether the usual explanations in the conflict literature might be behind these results. This has two purposes. On the one hand, to check whether some omitted variables might be behind our results. This also serves to check whether the exclusion restriction holds. On the other hand, to provide some evidence that supports these explanations. We look at state capacity and governance, and opportunity cost of conflict explanations. As variables of state capacity and governance we use the number of institutions per one thousand inhabitants in 1995 and the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. The first variable measures institutional presence in different dimensions like security, law enforcement, financial sector, social sector and bureaucracy. The intuition is that the larger the institutional presence in a given municipality, the larger the state capacity and governance there. Interestingly, both paramilitary and guerrilla attacks decrease with the presence of institutions (see column (3) of Tables 3 and 4). The result on paramilitaries is in line with findings of Acemoglu et al. (2013) who show that paramilitaries somewhat replace the state in those municipalities where the presence of state is scarce. The results for the proportion of votes are reported in column (5) of Panels A and B in Tables 3 and 4. They show that election results has no significant effect on both paramilitary and guerrilla attacks. In column (6) we report the results including all controls. Significance and signs of the previous coefficients are preserved. As a variable of opportunity cost of conflict we use the proportion of households with unmet basic needs in 1993. The idea is that the opportunity cost of making war is smaller for poor households. Of course, the variable is also related to opportunities to predate. Irregular armies might attack richer municipalities to seek rents. Results show that poverty has no effect on the intensity of conflict (see column (4)of Panels A and B in Table 3). Poverty has a positive effect on the onset of guerrilla attacks and no effect on the onset of paramilitary attacks (see column (4) of Panel B in Table 4). Findings for the onset of guerrilla attacks are compatible with the opportunity cost story. Our results are robust to controlling for measures of opportunity cost of conflict and state capacity and governance. They suggest that public policies that are useful to prevent conflict are not necessarily the same as those that are useful to mitigate conflict. Mobility 9. The tobit results in the Appendix show that the negative effect of road density on conflict is larger for those municipalities that are already suffering paramilitary and guerrilla attacks. 15 Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table 4: Onset of Conflict - Road Density - Education Quality Road Density Education Quality (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.564*** (0.0935) 0.212*** (0.0381) -0.364*** (0.0899) 0.129*** (0.0451) -0.282*** (0.0918) 0.111** (0.0452) -0.0462*** (0.0144) -0.362*** (0.0900) 0.0779 (0.0585) -0.375*** (0.0936) 0.145*** (0.0464) -0.0156 (0.0143) -0.285*** (0.0953) 0.0704 (0.0598) -0.0507*** (0.0141) -0.0384 (0.0281) -0.00954 (0.0145) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 -0.0324 (0.0261) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density Education Quality (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.706*** (0.134) 0.0657* (0.0390) -0.455*** (0.132) 0.0527 (0.0449) -0.433*** (0.138) 0.0525 (0.0487) -0.0266 (0.0213) -0.460*** (0.134) 0.180*** (0.0610) -0.455*** (0.135) 0.0942** (0.0464) 0.00989 (0.0141) -0.410*** (0.143) 0.242*** (0.0681) -0.0444** (0.0183) 0.0943*** (0.0293) 0.00667 (0.0141) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.0814*** (0.0259) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density in 1949 Panel C: First Stages (1) F-test R2 1st stage Education Attainment in 1993 F-test R2 1st stage Observations Other Controls Department FE 0.089*** (0.0288) 41.493*** 0.2246 0.3875*** (0.0309) 82.447*** 0.1678 0.084*** (0.0242) 26.427*** 0.4719 0.3701*** (0.0295) 81.799*** 0.5632 0.091*** (0.0240) 21.953*** 0.5368 0.3586*** (0.0301) 74.468*** 0.5733 0.082*** (0.0275) 17.036*** 0.472 0.179*** (0.0395) 10.365*** 0.5877 0.077*** (0.0273) 25.284*** 0.4773 0.3622*** (0.0307) 72.723*** 0.5596 0.0844*** (0.0243) 13.428*** 0.5506 0.172*** (0.0427) 8.207*** 0.5905 1,002 1,002 X X 948 X X 1,002 X X 934 X X 885 X X Note: OLS regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. of public investments might pay a role. Investments in roads are not movable and might generate new economic opportunities by reducing cost of transportation or making possible other investments. In contrast, investments in education are not. They help to accumulate human capital of people that might migrate. The relationship between migration and conflict is complex. There is evidence showing that violence has a non-linear effect on migration 16 (Bohra-Mishra et al., 2011). The impact of education policies will depend on who migrates, particularly important if migrants are relatively poor or relatively rich. If investments in education increases migration of more educated people to, say, the big cities, we may end up in a situation with more inequality across municipalities, which can in turn exacerbate conflict. This analysis requires data at the household level and goes beyond the scope of this paper . 6 Final Remarks Is there any empirical evidence regarding the impact of the provision of public goods on the onset and intensity of conflict? Which are the most effective public policies to reduce conflict? To answer these questions, this paper has addressed an important and yet to be unveiled issue regarding the determinants of the violent conflict in Colombia. We analyse whether two public policies that are frequently mentioned as effective to reduce conflict are effective, that is, whether public investments in roads and education reduce conflict. Our main findings show that conflict goes down with the provision of public road infrastructures; however, results for investments in education seems not to have a clear cut impact on conflict. These findings are robust to controlling for measures of state capacity, governance, opportunity cost of conflict, population size, coca crops, geographical and welfare controls. This opens the possibility for alternative explanations: it might have to do with the immobility/mobility of roads and education. There is already some literature that points out to the role of public goods in conflict and rent-seeking behavior (see Esteban and Ray, 2001 and Katz et al. 1990). Our results, framed in the existent literature on the relationship between public goods and conflict, seem to point out that the finding on roads is compatible with the idea that having more access to roads might reduce opportunity cost of conflict and increase state capacity and governance. Any land reform intended to improve living conditions of the rural population should consider policies that increase access to roads as a key complementary policy. The finding on education is in line with the fact that more educated people might emigrate to big cities going away from regions in conflict. Policy recommendations are straightforward. Most policy efforts in Colombia have been put into the war against drugs, including coca eradication. Those efforts must be complemented with investments in public infrastructures. References [1] Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J.A., Santos, R.J., 2013. The Monopoly of Violence: Evidence from Colombia. Journal of the European Economic Association, European Economic 17 Association, 11 (s1), pages 5-44. [2] Angrist, J., Kugler, A., 2008. Rural windfall or a new resource curse? coca, income and civil conflict in Colombia. The Review of Economics and Statistics 90(2): 191-215. [3] Barrera, F., Ibáñez A., 2004. Does Violence Reduce Investment In Education? A Theoretical And Empirical Approach. Documentos CEDE No. 2004-27. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [4] Berman, E., Shapiro, J.N., Felter, J.H., 2011. Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq, Journal of Political Economy, 119(4): 766 819. [5] Berman, E., Felter, J.H., Kapstein E., Troland E., 2012. Predation, Economic Activity and Violence: Evidence from Philippines, NBER working paper 18375 [6] Berman, E., Shapiro, J.N., Felter, J.H., 2013. Modest, Secure, and Informed: Successful Development in Conflict Zones, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 103(3): 512-517. [7] Besley, T., Persson, T., 2009. The Origins of State Capacity: Property Rights, Taxation, and Politics. American Economic Review, 99(4): 1218-44. [8] Besley, T., Persson, T., 2011. Pilars of Prosperity: The Political Economics of Development Clusters, Princeton University Press [9] Björklund, A., Salvanes, K. G., 2011. Education and Family Background: Mechanisms and Policies, Handbook of the Economics of Education, Elsevier. Edited by Erik Hanushek, Stephen Machin and Ludger Woessmann. Volume 3, Chapter 3, Pages 201–247. [10] Bohra-Mishra, P., Massey, D., 2011. Individual Decisions to Migrate During Civil Conflict, Demography 48 (2): 401-424. [11] Bush, K., Saltarelli, D., 2000. The two faces of education in ethnic conflict. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. [12] Collier, P., Hoeffler, A., 2004. Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxford Economic Papers, Oxford University Press, vol. 56(4), pages 563-595, October. [13] Davies, L., 2004. Education and conflict: complexity and chaos. London: Routledge. [14] Dı́az, A.M., Sánchez, F., 2004. Geography of Illicit Crops (Coca Leaf) and Armed Conflict in Colombia. The Development Research Centre, Development Studies Institute, London School of Economics (February 2004). 18 [15] Dube, O., Vargas, J.F., 2013. Commodity Price Shocks and Civil Conflict: Evidence from Colombia. Review of Economic Studies. F orthcoming. [16] Dueñas, L., Sanchéz, F., 2007. Does Armed Conflict Affect the Poorest? The Case of School Dropout in Eastern Colombia. Working Paper. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [17] Esteban, J., Ray, D., 2001. Collective action and the group size paradox. American Political Science Review, 95 (3): 663-672. [18] Frankel, J., 2010. The Natural Resource Curse: a Survey, NBER Working Paper No. 15836 [19] Katz, E., Nitzan, S., Rosenberg, J., 1990. Rent-seeking for pure public goods. Public Choice 65: 49-60. [20] McGlynn, C., 2009. Peace education in conflict and post-conflict societies: Comparative perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [21] Miguel, E., Satyanath, S., Sergenti, E., 2004. Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Journal of Political Economy 112(4): 725-753. [22] Ministry of National Defense of Colombia, 2000. El narcotráfico: una amenaza para la seguridad nacional. October, 2000. [23] Novelli, M., 2010. Education, conflict and social (in)justice: insights from Colombia. Educational Review 62(3): 271-285. [24] Rodrı́guez, C., Sánchez, F., 2009. Armed Conflict Exposure, Human Capital Investments and Child Labor: Evidence from Colombia. Documentos CEDE No. 2009-05. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [25] Rodrı́guez, C., Sánchez, F., 2010. Books and Guns. The Quality of Schools in Conflict Zones. Documentos CEDE No. 2010-38. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [26] Sánchez, F., Dı́az. A., 2005. Los efectos del conflicto armado en el desarrollo social colombiano, 1990-2002. Documentos CEDE No. 2005-58. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [27] Scoones, D., 2013. Winning Hearts and Minds: Public Good Provision in the Shadow of Insurgency, Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy, 19 (1): 17-31. [28] Solé-Ollé, A., 2003. Electoral accountability and tax mimicking: the effects of electoral margins, coalition government, and ideology. European Journal of Political Economy, 19 (4): 685-713. 19 [29] United States General Accounting Office, National Security and International Affairs Division, 1994. Drug Control: US Drug Interdiction Issues in Latin America, October 1994. [30] Villegas, L.C., Duque, J.C., 2009. Diez años de atentados a la infraestructura del paı́s. In Echavarria, S. H., editor, Seguridad pública: Tres aproximaciones. Centro de Análisis Polı́tico, ISBN: 958-44-5928-2. 20 A Probit (onset) and Tobit (intensity) results Table A.1: Naive estimations VARIABLES Paramilitaries Onset Intensity Guerrilla Onset Intensity Road Density -0.0241 (0.0453) -0.319*** (0.119) -0.253*** (0.0436) -0.376*** (0.0858) Education Quality 0.0441 (0.0285) 0.231** (0.107) 0.00205 (0.0277) 0.125* (0.0702) X X 873 X X 885 X X 859 X X 885 Other Controls Department FE Observations Note: Marginal effects of Probit regressions for onset and of Tobit regressions for intensity. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Included controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall, coca crops in 1994, number of institutions per 1,000 inhabitants in 1995, average education attainment of household heads in 1993, poverty in 1993 and winner voting proportion in mayoral elections in 1997. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. 21 Panel C: First Stage Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table A.2: Intensity of Conflict - Road Density Road Density (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -2.771*** (1.056) -3.492** (1.543) -2.252** (1.053) -0.530*** (0.133) -3.677** (1.660) -4.118** (1.932) -0.0615 (0.115) -2.811** (1.309) -0.531*** (0.158) -0.236 (0.175) -0.115 (0.0990) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 -0.202 (0.191) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -1.963*** (0.571) -1.540*** (0.572) -1.335** (0.534) -0.156 (0.0969) -1.456** (0.589) -1.700** (0.689) 0.0501 (0.0706) -1.001* (0.592) -0.275*** (0.0729) 0.152* (0.0831) 0.0237 (0.0675) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.127 (0.0800) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density in 1949 0.128*** (0.0320) 0.084*** (0.0260) 0.0920*** (0.0236) 0.0829*** (0.0270) 0.0772*** (0.0267) 0.0844*** (0.0237) F-test R2 1st stage 16.04*** 0.022 14.37*** 0.4214 14.60*** 0.5368 9.05*** 0.472 7.99*** 0.4773 12.04*** 0.5506 1,002 1002 X X 948 X X 1,002 X X 934 X X 885 X X Observations Other Controls Department FE Note: Coefficients are marginal effects of Tobit regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. 22 Panel C: First Stage Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table A.3: Onset of Conflict - Road Density Road Density (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.802*** (0.117) -1.176*** (0.175) -1.162*** (0.322) -0.188** (0.0791) -1.202*** (0.170) -1.206*** (0.171) -1.294*** (0.299) -0.151* (0.0852) -0.126 (0.0896) -0.0469 (0.0446) 873 Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 -0.0977 (0.0641) Winner voting in 1997 Observations Road Density 1,002 990 935 990 -0.0279 (0.0390) 922 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -0.923*** (0.101) -1.365*** (0.179) -1.435*** (0.302) -0.0181 (0.0561) -1.304*** (0.227) -1.400*** (0.176) 0.0199 (0.0423) -1.301*** (0.448) -0.0463 (0.0695) 0.299** (0.119) -0.00511 (0.0509) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.197* (0.108) Winner voting in 1997 Road Density in 1949 0.128*** (0.0320) 0.084*** (0.0260) 0.0917*** (0.0236) 0.0826*** (0.0270) 0.0772*** (0.0267) 0.0844*** (0.0238) F-test R2 1st stage 16.04*** 0.022 14.37*** 0.4214 14.60*** 0.5368 9.05*** 0.472 7.99*** 0.4773 12.04*** 0.5506 1,002 974 X X 919 X X 974 X X 908 X X 859 X X Observations Other Controls Department FE Note: Coefficients are marginal effects of Probit regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. 23 Panel C: First Stage Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table A.4: Intensity of Conflict - Education Education Quality (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 1.281*** (0.298) 0.788*** (0.296) 0.859*** (0.307) -0.464*** (0.119) 1.191 (0.740) 0.906*** (0.328) -0.0692 (0.0783) 1.223 (0.813) -0.437*** (0.140) 0.161 (0.343) -0.0771 (0.0793) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.250 (0.319) Winner voting in 1997 Education Quality (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 0.322** (0.140) 0.0504 (0.129) 0.115 (0.145) -0.137 (0.0896) 0.665* (0.361) 0.148 (0.140) 0.0456 (0.0632) 1.077** (0.481) -0.191** (0.0781) 0.499** (0.212) 0.0331 (0.0671) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.374** (0.164) Winner voting in 1997 Education attainment in 1993 0.388*** (0.0309) 0.370*** (0.0290) 0.359*** (0.0295) 0.180*** (0.0388) 0.362*** (0.0301) 0.172*** (0.0417) F-test R2 1st stage 156,67*** 0,1678 157.05*** 0,5632 141.57*** 0,5735 20.66*** 0,5877 138.67*** 0,5596 16.28*** 0,5905 1,002 1,002 X X 948 X X 1,002 X X 934 X X 885 X X Observations Other Controls Department FE Note: Coefficients are marginal effects of Tobit regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature, rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. 24 Panel C: First Stage Panel B: Guerrilla Attacks Panel A: Paramilitary Attacks Table A.5: Onset of Conflict - Education Education Quality (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 0.486*** (0.0780) 0.103 (0.179) 0.212 (0.197) -0.232*** (0.0822) -0.274 (0.448) 0.193 (0.193) -0.0191 (0.544) -0.227** (0.0925) -0.181 (0.239) -0.0361 (0.0534) 873 Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 -0.222 (0.201) Winner voting in 1997 Observations Education Quality 1,002 990 935 990 -0.0586 (0.0522) 922 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 0.177* (0.100) -0.102 (0.179) -0.220 (0.195) -0.0219 (0.0553) 0.678* (0.378) 0.0611 (0.188) 0.0363 (0.0473) 0.861** (0.355) 0.0165 (0.0668) 0.536*** (0.138) 0.0300 (0.0435) Institutions in 1995 Poverty in 1993 0.468*** (0.156) Winner voting in 1997 Educational attainment in 1993 0.388*** (0.0309) 0.371*** (0.0291) 0.359*** (0.0297) 0.182*** (0.0390) 0.362*** (0.0303) 0.174*** (0.0420) F-test R2 1st stage 156,67*** 0,1678 157.05*** 0,5632 141.57*** 0,5735 20.66*** 0,5877 138.67*** 0,5596 16.28*** 0,5905 1,002 1,002 X X 948 X X 1,002 X X 934 X X 885 X X Observations Other Controls Department FE Note: Coefficients are marginal effects of Probit regressions. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Institutions in 1995 are the number of institution per 1000 inhabitants including security, law enforcement, financial, social and bureaucratic institutions. Poverty in 1993 is the proportion of households in the municipality with unmet basic needs. Winner voting in 1997 is the proportion of votes obtained by the winner in mayoral elections in 1997. Other controls are: average municipality population, longitude, latitude, temperature rainfall and coca crops in 1994. *** is significant at the 1% level. ** is significant at the 5% level. * is significant at the 10% level. 25