This article in PDF-format

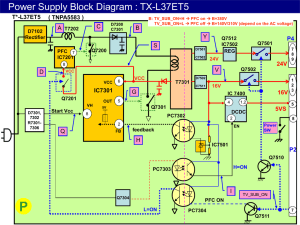

advertisement