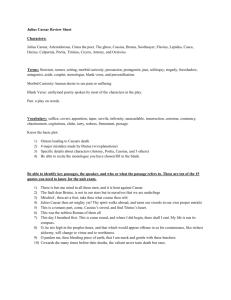

foundations_notes

advertisement