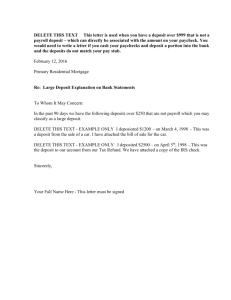

PDF format

advertisement