Anticipated acquisition by Reckitt Benckiser of the K-Y

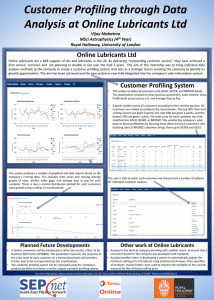

advertisement