Transporting Goods into Canada by Road

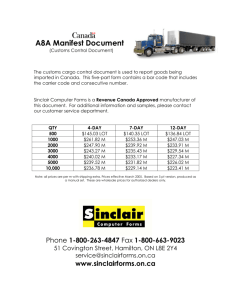

advertisement

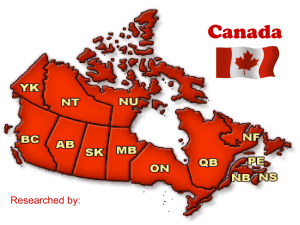

Transporting Goods into Canada by Road By Will Westeringh, Managing Partner, Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP Vancouver Introduction With the United States (“USA”) and Canada being each other’s largest trading partners, a significant volume of goods cross the USA/Canada border every day. Given the length of the border between the two countries, it is not surprising that most of these traded goods are transported by truck. Due to the economic importance of this bilateral trade to Canada, authorities tasked with regulating trucking, both at the Federal and Provincial level, have in many cases adopted uniform, or alternatively similar, regulatory regimes making it easier for trucking companies to transport goods from USA to Canada, and within Canada. However, despite efforts to harmonize rules and regulations, the fact that an international border is involved, and that each Canadian province has jurisdiction to regulate motor vehicle transportation within its own borders, means transporting goods by road between the USA and points within Canada, is affected by a variety of rules, regulations and policies. Being aware of some of the issues involved, should be of some assistance to a USA based carrier intending to transport goods into Canada. This paper is intended to touch on some of the most important issues, although it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a comprehensive overview. Canada – some quick facts • • • Population 30 Million Geographic size – 9,976,140 sq km (3,851,809 sq miles) Length of common border with USA is 6416 km (2878 km land) or 3,987 miles (1788 miles land) DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 1 • • 75% of Canada’s population lives within 150 km (90 miles) of the USA border. • • Official languages – English and French Internal structure – 10 provinces and 3 territories Legal system • • • • • • Federal – Common Law Provincial • 9 provinces Common Law • Quebec Civil Law Standards of measurement – metric Largest provinces – Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta Total USA/Canada Trade, 2005 US $400 Billion Total Trade value transported by Truck, 2005, 62% Legislation relevant to carriers transporting goods from the USA into Canada General: 1. For Border crossing: − − 2. 3. Customs Act (Federal) Canada Border Service Agency Act (Federal) For Dangerous Goods: Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act (Federal). All provinces and territories have adopted these regulations. For Taxation and other Duties: − − − − 4. Customs Tariff, Excise Act Excise Tax Act Special Import Measures Act North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”) For Vehicle Standards: − − 5. 6. Motor Vehicle Safety Act (Federal) Motor Carrier/Transport Acts (Provincial) For Criminal Violators – Canada Criminal Code (Federal) For Traffic Violations and Accidents – Provincial Statues DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 2 Issues relevant to the Importation of Goods into Canada Reporting requirements: With minor exception, all commercial goods that are imported into, exported from, or moving in transit through Canada must be reported to Canada Customs. The requirement to report goods to Customs is generally effected through the presentation of a Customs approved cargo control document. The use of custom brokers to facilitate the transportation of goods across is common. All commercial goods transported into Canada are subject to customs duty and the goods and services tax (GST), unless they are exempt or free of duties. The value of the goods must be converted into Canadian funds to determine the duties payable. Depending on the nature of the goods or their value, special levies or taxes may apply, including excise duty and excise tax on luxury items like jewellery or alcohol. There are 22 customs offices that offer commercial service 24 hours a day. Others provide commercial service from 8:00 a.m. to midnight, and others are only open to release commercial shipments during regular office hours (e.g., 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.). The vendor or exporter should give the carrier a sales receipt or invoice that describes the goods in detail and shows the purchase price. The vendor or exporter should also provide the carrier with a certificate of origin as some goods may qualify for lower duty rates, such as those outlined in the NAFTA. Bills of Lading are discussed below. FAST: The Free and Secure Trade (FAST) program is a joint Canada-USA initiative involving the Canada Border Services Agency, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, and the United States Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP). FAST supports moving pre-approved eligible goods across the border quickly and verifying trade compliance away from the border. It is a harmonized commercial process offered to pre-approved importers, carriers, and registered drivers. Shipments for approved companies, transported by approved carriers using registered DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 3 drivers, will be cleared into either country with greater speed and certainty, and at a reduced cost because of shorter border delays. Bond Requirement: Only carriers or freight forwarders that have filed security with Customs are permitted to transport in bond goods between points in Canada. Security can be posted on a single trip or general authorization basis. Carriers transporting more than five shipments into Canada annually are encouraged to apply for a general authorization in order to expedite Customs processing formalities Carrier Identification: For the purpose of identifying bonded carriers and freight forwarders, a carrier code is assigned to a company upon authorization of bonded status. This carrier code number must be shown on all cargo control documents presented to Customs. Cargo reporting: Unless exempted under the regulations, commercial goods being imported into Canada must be reported by the carrier to Customs on an approved cargo control document or via electronic data interchange (“EDI”). Identifying Cargo: The actual number of packages, parcels, drums, etc., being imported, must be shown on the cargo control document. The cargo control document may be completed to show the number of pieces in the quantity section of the document with the number of transportation units (i.e., skids, pallets, containers) shown in the description of goods section. Alternatively, the number of transportation units may be shown in the quantity section with the number of pieces shown in the description of goods section. In both cases, where more than one commodity is reported on a cargo control document, the total pieces must be indicated. Shortages in Cargo: Acceptable evidence of a shortage can consist of written evidence of payment of a claim by a foreign carrier, a statement by a Customs or peace officer that the goods were lost or destroyed through an accident, fire, or documentation from the vendor, exporter, shipper or warehouse operator at the point of departure attesting that a true shortage did exist and DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 4 was not the result of theft, loss, etc. Documentation originating from the carrier is not considered acceptable evidence of a shortage. A third party must substantiate shortages. Where evidence of a shortage cannot be provided, duties and taxes owing for the short goods must be paid. Overages (Excess) in Cargo: Overages found by Customs or the carrier must be documented immediately by the carrier on a cargo control document, and all copies must be presented to Customs for validation and processing. Penalties: As overages represent cargo that has not been reported to Customs as required under the Customs Act, when a Customs inspector discovers an overage during a Customs check or examination, the carrier may be assessed a penalty. Seizure: In the case of goods owned by the carrier, or where goods are being transported by a truck owned or controlled by the importer or shipper, Customs may seize both the unreported goods and the tractor-trailer unit. Obviously all cargo can be searched for illegal or banned substances, and if found, criminal charges can be laid, in addition to the imposition of penalties and fines. Records relating to goods transported into Canada should be maintained for a minimum of three years. These records can include charts of accounts, trip logs, movement history reports, and bills of lading. They may include paper documents or those stored electronically. Interpretation of the Contract: Any contract involving international transportation raises the question of what law applies to govern the interpretation of the contract and the relationship between the parties. If foreign law is applicable, it is pleaded as a fact and is ultimately proven as such.1 Modern jurisprudence indicates that the applicable law is that which has the closest and most real connection with the transaction2. In determining presumed intention, the court will be 1 2 Key v. Key (1930), 65 O.L.R. 232 (Ont. C.A.); Bausch and Lomb Optical Co. v. Maislin Tpd. Ltd. (1975). Ontario Bus Industries Inc. v. The Federal Calumet [1992] 1 F.C. 245. DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 5 examining the same factors that would require consideration under the “close connection” approach. Bill of Lading: The applicable Canadian law regarding the interpretation of the bill of lading is that of the jurisdiction where the bill of lading was issued, that being, in most cases, the point of original of the shipment.3 This factor was so influencing in ABB Power Generation Inc. V. CSX Transportation,4 where a shipment consigned to Ontario originated in the USA and American law was going to regulate the interpretation of the contract, that the court went as far as declining jurisdiction simpliciter altogether. Accidents: In Jensen v. Tolofson5 the court opined that the applicable law with respect to wrongs committed in Canada was the law of the province where the wrong was committed. By the same rule, USA carriers will be liable for tort under the province where the wrong was committed. Contracts performed by modern means: Where a contract is concluded by telephone it the law of the jurisdiction in which the offeror is located when his acceptance of the contract is communicated.6 This rule also applies to contract concluded by means of electronic transmissions.7The quote is the offer, and the location of the carrier when it receives acceptance of the quote is the jurisdiction whose laws regulate the interpretation of the contract. Where, however, the bill of lading stipulates a different result, the contract rules. In E. Fisher Equipment Ltd. v. Equipment Express Ltd.,8 when the shipment was moving from Ontario to Kentucky, the court applied United States law because the bill stated in the event of international shipments being covered by it, the provisions of the Federal Motor Carrier Act 1935 USA would apply. 3 See for example George C. Anspach Co. v. C.N.R.[1950]; Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., note 1. (1996), 47 C.P.C. (3d) 381 (Ont. Gen. Div.) 5 (1995) , 120 D.L.R. (3d) 289 (S.C.C.). 6 Viscount Supply Co., Re, [1963] 1 O.R. 640 (Ont. S.C.) 7 Eastern Power Ltd. v. Azienda Communicale Energia & Ambiente (1999), [1999] O.J. No. 3275, leave to appeal refused (2000), 2000 Carswell Ont. 2212 (S.C.C.) 4 DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 6 Transporting goods in Canada International Registration Plan (“IRP”): All 10 Canadian provinces are members of the IRP allowing commercial motor vehicles registered in their home jurisdictions, including in the USA, to operate between two or more jurisdictions, while registration fees and taxes are apportioned. Traffic regulations: Trucks are subject to a large number of traffic regulations, some federal, but most based upon the province in which they are hauling at any given time. Typically Canadian traffic regulations are similar to those found in most states, although speed limits and weights are typically posted in metric. Truck weights and dimensions: How heavy or long a truck can be encompasses literally hundreds of pages of provincial and territorial regulatory text, a special inter-jurisdictional task force and several inter-jurisdictional agreements, a raft of “special permits” (for trucks that exceed the normal weight and dimension limits), and a large infrastructure for enforcement (highway weigh scales and mobile inspectors). These regulations control how much weight a truck can have on a tire, an axle, and the vehicle or vehicle combination. They also control many of the dimensional aspects of a truck. The three NAFTA countries have established a special body to consider the integration of North American rules. Contacting brokers, accessing government websites or contacting government offices in the province of intended travel is often necessary if hauling unusual loads. Regulations are frequently similar, if not identical, to those in the USA. Vehicle Standards: New vehicles are manufactured in accordance with standards set in the federal Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Many of these standards, which are specifically set for trucks, are in accordance with USA standards. 8 (1992), 33 A.C.W.S. (3d) 345 (Ont. Gen. Div.) DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 7 Insurance Standards: All provinces have mandatory minimum third party insurance limits, often higher than in at least some states. Carriers entering Canada, and any particular province must comply with the provincial minimum limit. USA insurer must have filed a Power of Attorney and Undertaking (PAU), certifying it will honour provincial minimum limits, or carrier will need to purchase coverage equal to provincial minimum limit. Emissions: The control of truck emissions used to be handled by Transport Canada under the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, but since 2000 responsibility has been transferred to Environment Canada on the basis that one agency should set standards for both vehicle emissions and fuel. Emission standards are similar to those in the USA. Taxation: Trucks are subject to special regulations-regulations on how fuel tax is prorated among jurisdictions in which a truck operates, similar regulations for vehicle registration taxes, taxes (particularly in the USA) that have particular application to trucking companies, special treatment of some taxes (for example, the provincial sales tax) in the case of a purchase of a truck that is to be used extra-provincially, etc. Drug & Alcohol Testing: Canadian law does not require trucking companies to test employees for drug and alcohol use but since many large Canadian trucking companies operate into the USA, they must comply with United States drug and alcohol testing regulations. Seatbelts: Unless there is a medical reason rendering a person unable to wear one, seatbelts are mandatory in all provinces, when operating a motor vehicle. Safety: A federal program created national standards for hours of service, maintenance of log books, trip inspections, record retention, and other safety related requirements, which standards have been adopted in provincial regulations. Standards are similar to those in USA. DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 8 Vehicle Inspections: Provinces have adopted inspection and repair standards developed nationally by the Canadian Council of Motor Transporters Association. Provinces will typically accept proof that shows a vehicle has passed appropriate inspections in another jurisdiction. Trucks can be inspected at a border crossing, at weigh stations, or during random roadside locations selected by provincial authorities. Traffic offences: Traffic regulations are provincial and accordingly minor offences attract provincial fines. Serious offences such as criminal negligence causing death, impaired driving and possession of drugs are covered by the Federal Criminal Code of Canada. A USA driver with a criminal records may not be permitted entry to Canada. A driver charged with a serious criminal offence in Canada may be denied bail in some instances. As access to guns is much more restricted in Canada than in the USA, drivers should typically refrain from carrying guns in their trucks when crossing the border into Canada. DM_VAN/253729-13990/6713504.1 9