Orders page 1

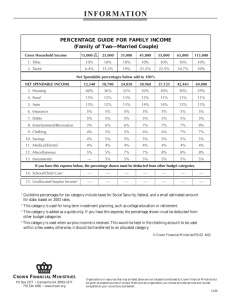

advertisement