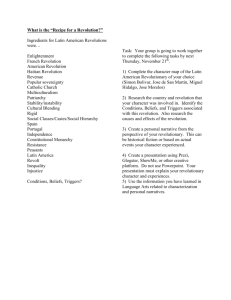

A People's History of the American Revolution:

advertisement