Early Childhood Education and Care in Dubai

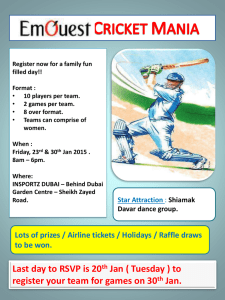

advertisement