File - Mrs. Hoyt's Classes

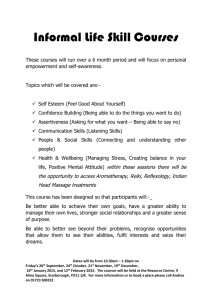

advertisement