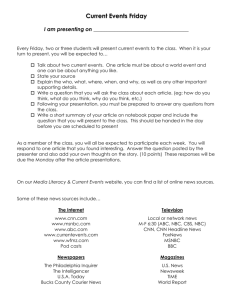

full text

advertisement