MALE REPRODUCTIVE

SYSTEM

Reproductive System

To Accompany: Anatomy and Physiology Text and

Laboratory Workbook, Stephen G. Davenport, Copyright

2006, All Rights Reserved, no part of this publication can be

used for any commercial purpose. Permission requests

should be addressed to Stephen G. Davenport, Link

Publishing, P.O. Box 15562, San Antonio, TX, 78212

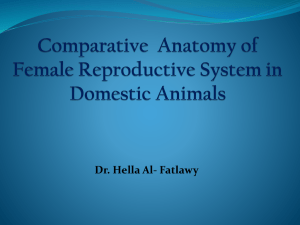

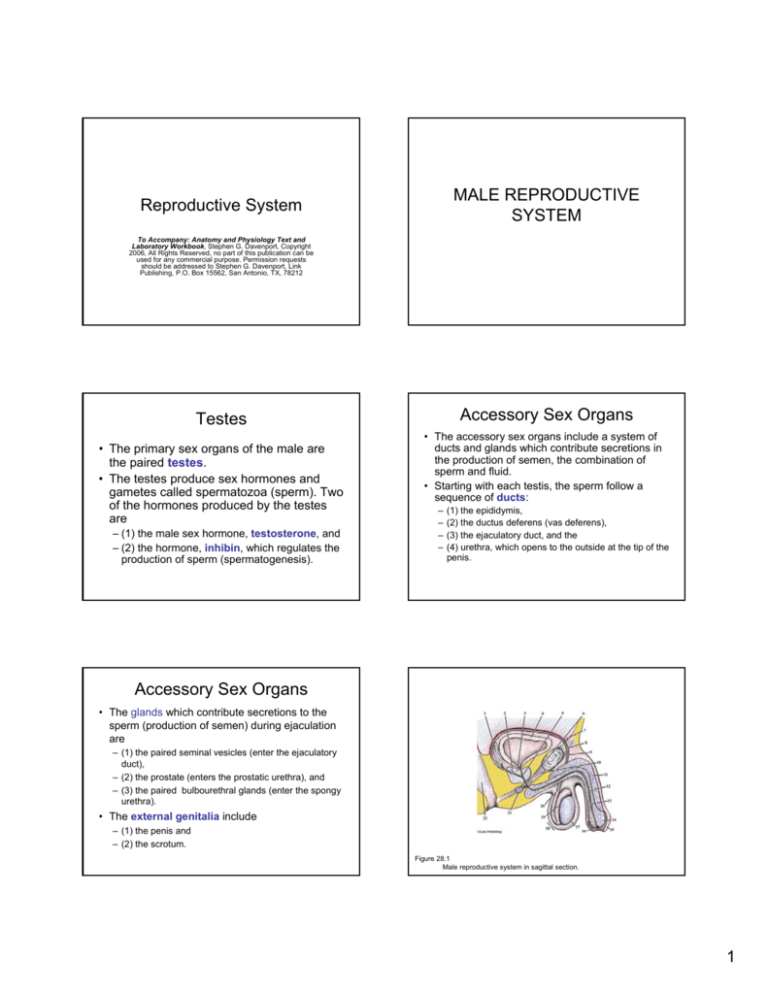

Accessory Sex Organs

Testes

• The primary sex organs of the male are

the paired testes.

• The testes produce sex hormones and

gametes called spermatozoa (sperm). Two

of the hormones produced by the testes

are

– (1) the male sex hormone, testosterone, and

– (2) the hormone, inhibin, which regulates the

production of sperm (spermatogenesis).

• The accessory sex organs include a system of

ducts and glands which contribute secretions in

the production of semen, the combination of

sperm and fluid.

• Starting with each testis, the sperm follow a

sequence of ducts:

–

–

–

–

(1) the epididymis,

(2) the ductus deferens (vas deferens),

(3) the ejaculatory duct, and the

(4) urethra, which opens to the outside at the tip of the

penis.

Accessory Sex Organs

• The glands which contribute secretions to the

sperm (production of semen) during ejaculation

are

– (1) the paired seminal vesicles (enter the ejaculatory

duct),

– (2) the prostate (enters the prostatic urethra), and

– (3) the paired bulbourethral glands (enter the spongy

urethra).

• The external genitalia include

– (1) the penis and

– (2) the scrotum.

Figure 28.1

Male reproductive system in sagittal section.

1

Male Reproductive System

• Scrotum

– The scrotum is the pouch that contains the testes.

The scrotum is divided into halves by a midline

septum for the housing of the right and left testes.

• Testes

– The paired testes produce sperm and hormones.

– Seminiferous tubules are located within the testes

and are the sites of the production of sperm and the

hormone, inhibin, which is involved in the regulation

of sperm production.

– Located in the connective tissue surrounding the

seminiferous tubules are the interstitial (Leydig) cells

which produce the sex hormone, testosterone.

Male Reproductive System

• Seminal vesicles

– The paired seminal vesicles are located posterior to the bladder.

The alkaline fluid produced by each seminal vesicle is

transported to an ejaculatory duct by each seminal vesicle’s

duct. During ejaculation, seminal fluid and sperm mix in the

ejaculatory duct and are propelled into the urethra (prostatic).

• Urethra

– The urethra is the tube that serves both the urinary and

reproductive systems and is divided into three regions,

– (1) the prostatic urethra (passes through the prostate gland)

– (2) the membranous urethra (passes through the urogenital

diaphragm)

– (3) the spongy urethra (passes through the penis and opens to

the exterior)

Male Reproductive System

• Epididymis (pl. epididymides)

– An epididymis is located posterior to each testis. The epididymis

receives sperm from the testis and is the site where the sperm

are stored and develop motility. During ejaculation, smooth

muscle contractions within the walls of its tubules force sperm

into the ductus (vas) deferens.

• Ductus (vas) deferens (pl. vasa deferentia)

– The ductus deferens is the tube that transports sperm from the

epididymis to the ejaculatory duct. The paired ejaculatory ducts,

are located within the prostate. Each is formed by the union of a

ductus deferens and a duct from a seminal vesicle. An

ejaculatory duct propels sperm (from the vas deferens) and the

secretions from a seminal vesicle into the urethra (prostatic).

Male Reproductive System

• Prostate gland

– The prostate gland is located inferior to the bladder

and surrounds the urethra (prostatic).

– It produces an alkaline fluid that during ejaculation

enters the urethra (prostatic) through several small

openings.

• Bulbourethral glands

– The paired bulbourethral glands are located inferior to

the prostate. They secrete an alkaline fluid that

enters the spongy (penile) urethra.

Male Reproductive System

• Penis

– The penis is attached by its proximal portion called

the root. The root leads to the body (shaft) that

terminates in the glans penis.

– The glans penis is surrounded by the prepuce

(foreskin) unless the prepuce was removed by a

procedure called circumcision.

– The body of the penis consists of three regions of

erectile tissue, two dorsal corpora cavernosa (only

one corpus cavernosum is seen in a sagittal section)

and a medial corpus spongiosum. The corpus

spongiosum surrounds the spongy (penile) urethra.

– The glans penis surrounds the terminus of the

urethra, the external urethral orifice.

TESTES

The testes are located in the scrotum.

They are slightly oval shaped and

average about two inches in length and

one inch in width.

2

Testes

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

• Each testis is surrounded by two layers of

connective tissues, the

– (1) tunica vaginalis- forms a capsule (lined with

serous membranes) which surrounds the testis

– (2) tunica albuginea- lines the surface of the testis. A

portion of the tunica albuginea folds into the testis and

divides it into many compartments called lobules.

Each lobule consists of one to three coiled

seminiferous tubules, which contain the germinal

(spermatogenic) epithelium.

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

Figure 28.3

Scanning power photograph of a cross section of a testis (rat). The testis

houses numerous highly convoluted seminiferous tubules and interstitial cells.

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

• Tunica albuginea

– The tunica albuginea is the connective tissue

layer covering the surface of the testis.

• Interstitial (Leydig) cells

– The interstitial (Leydig) cells are located in the

connective tissue around the seminiferous

tubules. The interstitial (Leydig) cells are

endocrine in function and produce the

hormone testosterone.

Figure 28.2

Scanning power photograph of a section of a testis and its associated

epididymis. The testis houses numerous highly convoluted seminiferous tubules.

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

Figure 28.4

Scanning power photograph of a portion of a longitudinal section of a

testis (human) showing its organization into lobules. Each lobule contains one to

three highly convoluted seminiferous tubules

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

• Seminiferous tubules

– The seminiferous tubules are the convoluted tubules

within the testis where sperm production occurs by

the process called spermatogenesis.

– Additionally, the seminiferous tubules are the sites of

the production of the regulatory hormone called

inhibin. The tubules are associated with connective

tissues, lymphatic vessels, blood vessels (capillaries

are especially abundant), and interstitial (Leydig)

cells.

3

Lab Activity 1 - Testes

• Spermatogenesis

– Spermatogenesis is the process of the production of

the male gametes, the spermatozoa, or sperm.

– Spermatogenesis involves

• the meiotic division of primary spermatocytes to secondary

spermatocytes (meiosis I),

• the meiotic division of the secondary spermatocytes to

spermatids (meiosis II), and the

• transformation of the spermatids into spermatozoa

(spermiogenesis).

• Spermiogenesis

– Spermiogenesis is the process of transformation of

spermatids into spermatozoa.

MEIOSIS

and Gamete Production

Meiosis is nuclear division in gamete

producing cells that results in a reduction in

the number of chromosomes from diploid (2n)

to haploid (n).

Meiosis

Meiosis

• In meiosis, one of each pair of

homologous chromosomes is distributed

to a daughter cell.

• Haploid daughter cells function as

gametes, sperm and eggs.

• The number of chromosomes that are

found in the somatic (body) cells of the

organism is referred to as the diploid

number (2n). The diploid number of

chromosomes in humans is 46.

• Each chromosome has a homologous

chromosome, a chromosome that carries the

same genes (mostly). Thus, in humans there are

23 pairs of homologous chromosomes.

• The set of one each of the homologous

chromosomes, or the set of different

chromosomes, is described as the haploid (n)

number.

• The haploid chromosome number for the human

is 23 chromosomes, and it is this number found

in the sperm and egg.

• Before meiosis begins, the chromosomes are

replicated

• Meiosis is divided into meiosis I and meiosis II

Meiosis I

Meiosis I

• Meiosis I

– In meiosis I, the replicated homologous chromosomes

are paired, an event called synapsis.

– During synapsis crossing-over of portions of the

chromosomes (chromatids) occurs.

– After crossing-over occurs, the pairs are separated,

and one replicated chromosome (a homologous

chromosome) is distributed to each daughter cell.

• Thus, the daughter cells (n) of Meiosis I have

only one of each type of replicated chromosome.

Figure 28.5

4

Meiosis II

Meiosis II

• Entering into meiosis II are the daughter cells from

meiosis I.

• These cells have one of each type of chromosome (one

homolog) in the replicated form (a replicated

chromosomes consists of two sister chromatids).

• In meiosis II, the sister chromatids are separated and

one of each sister chromosome is distributed to the

daughter cells. Thus, the daughter cells, which function

as gametes, have only one of each homologous

chromosome.

• The gametes are haploid (n). Fusion of the gametes, a

sperm and an egg, during fertilization produces the

diploid (2n) number of chromosomes and produces a

single cell called a zygote.

Figure 28.5

Meiosis - Spermatogenesis

• Spermatogenesis is the process of male gamete

(sperm) production. Spermatogenesis occurs in the

seminiferous tubules of the testis.

• Precursor (stem) cells called spermatogonia, located at

the periphery of the seminiferous tubules, undergo

mitotic divisions. Some of the daughter cells remain at

the periphery of the tubules as precursor cells. Others

differentiate into primary spermatocytes (2n.)

• Primary spermatocytes enter meiosis I and produce two

haploid daughter cells called secondary spermatocytes

(n.)

• The two secondary spermatocytes enter meiosis II and

each produces two haploid spermatids (n.)

• Spermatids undergo a process of transformation called

spermiogenesis and develop into spermatozoa

(sperm.)

Meiosis - Spermatogenesis

Figure 28.6

Spermatogenesis is the process of male gamete production. Meiosis reduces

the diploid human chromosome number of 46 to the haploid number of 23. Meiosis

assures that each of the gametes contains only half of the homologous chromosomes.

Lab Activity 2 – Testis

Lab Activity 2 – Testis

Spermatogenesis - Microscopic Study

Spermatogenesis - Microscopic Study

Figure 28.7

Section of testis showing seminiferous tubules, c.s.

Figure 28.8

High power photograph of a seminiferous tubule (rat) showing cell

division. Dividing cells are not always observed in testis preparations.

5

Lab Activity 2 – Testis

Lab Activity 2 – Testis

Spermatogenesis - Microscopic Study

Spermatogenesis - Microscopic Study

Figure 28.9

Low power photograph of a seminiferous tubule. The specific identification of the

cell types is difficult and is based mostly by their sequence of development.

Figure 28.10

High power photograph of a seminiferous tubule (rat) showing sustentacular cells

and spermatogenic cells. The cells are mostly identified by the location and shape

of their nuclei. Interstitial cells are located around the seminiferous tubule.

Sustentacular cells

Sustentacular cells

• The sustentacular cells are permanent residents

of the germinal epithelium and undergo very little

if any cell division.

• The sustentacular cells occupy the space

between the outer margin of the seminiferous

tubule and its lumen. The sustentacular cells

partially invest the spermatogenic cells, which

causes the spermatogenic cells to be located

between the plasma membranes of adjacent

sustentacular cells.

• Sustentacular cells function to support the

cells of spermatogenesis, and thus, are often

called “nurse” cells.

• In addition to metabolically supporting the

spermatogenic cells, sustentacular cells function

to support spermatogenesis by the production of

the blood-testis barrier.

• The blood-testis barrier is necessary to prevent

an auto-immune response toward the haploid

spermatogenic cells located toward the lumen of

the seminiferous tubule.

• The fusion of the membranes of the adjacent

sustentacular cells divides the seminiferous

tubes into an outer basal compartment and an

inner luminal compartment.

Sustentacular cells

Sustentacular cells

Figure 28.11

Sustentacular cells fuse by tight junctions to form a blood-testis barrier.

The sustentacular cells fuse to divide the seminiferous tubule into a basal

compartment and a luminal compartment. The inner luminal compartment, which

contains haploid cells, has no direct blood exchange.

Figure 28.11

Sustentacular cells fuse by tight junctions to form a blood-testis barrier.

The sustentacular cells fuse to divide the seminiferous tubule into a basal

compartment and a luminal compartment. The inner luminal compartment, which

contains haploid cells, has no direct blood exchange.

6

Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

MALE HORMONAL

REGULATION

Follicle-stimulating hormone

(FSH)

Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

• Sustentacular Cells

• The sustentacular cells also function in the

regulation of spermatogenesis by responding to

blood levels of follicle stimulating hormone

(FSH).

• FSH promotes the release of androgen binding

protein (ABP) from the sustentacular cells.

– Androgen binding protein targets the spermatogenic

cells and results in their increased uptake of

testosterone. Increased stimulation of the

spermatogenic cells by testosterone results in an

increased rate of spermatogenesis

Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

• Sustentacular Cells

• Sustentacular cells also release the hormone

inhibin, which functions in the regulation of the

release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)

from the anterior pituitary gland.

– Increased stimulation of the sustentacular cells by

FSH, increases inhibin release, which by negative

feedback targets the hypothalamus, reduces the

release of GnRH, which reduces the release of FSH.

– Decreased levels of inhibin result in hypothalamic

increase of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH),

which results in an increase of follicle-stimulating

hormone (FSH).

Luteinizing hormone (LH)

• Luteinizing hormone (LH) is produced and

released from the anterior pituitary gland (pars

distalis).

• Luteinizing hormone (LH) targets the interstitial

cells of the testes and increases the release of

testosterone.

• Negative feedback controls the secretion of

luteinizing hormone (LH). Increased levels of

testosterone result in hypothalamic reduction of

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH).

Figure 28.12

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is

produced and released from the

anterior pituitary (pars distalis).

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

targets the sustentacular cells.

Sustentacular cells release androgen

binding protein (ABP) and inhibin.

Androgen binding protein targets the

spermatogenic cells and inhibin

targets the hypothalamus.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

Figure 28.13

The release of luteinizing hormone

from the anterior pituitary is regulated

by gonadotropin-releasing hormone

(GnRH). Luteinizing hormone (LH) is

produced and released from the

anterior pituitary (pars distalis).

Luteinizing hormone (LH) targets the

interstitial cells to increase

testosterone production.

7

Spermatozoa (Sperm)

SPERMATOZOA (SPERM)

Spermatozoa are the gametes of

the male.

Spermatozoa (Sperm)

• Head of Sperm

– The head of the spermatozoon contains the

nucleus of the cell.

– A structure called the acrosomal cap (or

acrosome) is located at the tip of the head.

The acrosomal cap releases enzymes which

function in the penetration of the egg.

• The nucleus of each sperm contains one

of each homologous chromosome for a

total of 23 chromosomes.

• A spermatozoon is divided into three

regions, a

– head,

– midpiece, and the

– tail.

Spermatozoa (Sperm)

• Midpiece of Sperm

– The midpiece of the spermatozoon is connected to the head by a

short neck.

– The neck is the origin of the microtubules which pass through

the center of the midpiece into the tail, or flagellum. Numerous

mitochondria are located at the periphery of the microtubules

and provide the energy (ATP) to drive the movement the

microtubules.

– The movement of the microtubules results in the movement of

the tail (flagellum). Simple sugars such as fructose are absorbed

from the fluid surrounding the spermatozoa and serve as the

primary fuel molecule in the production of ATP.

• Tail of Sperm

– The tail, or flagellum, contains microtubules and functions to

move the spermatozoon.

Lab Activity 3 - Sperm

EPIDIDYMIS

The ductus epididymis functions

as the site where sperm are

stored and mature.

Figure 28.14

Oil immersion photograph of human spermatozoa. A spermatozoon is

divided into a head, midpiece, and a tail (flagellum).

8

Epididymis

Epididymis

• \The seminiferous tubules of the testis merge into a

region of the testis called the rete testis. The rete testis

consists of a group of small ducts lined with simple

cuboidal epithelium that deliver spermatozoa into the

efferent ducts located in the head of the epididymis. The

efferent ducts (ductuli efferentes) are lined with ciliated

columnar epithelium and merge to form the highly coiled

long duct of the body and tail of the epididymis, the

ductus epididymis.

• The ductus epididymis functions as the site where

sperm are stored and mature. The ductus epididymis

forms the ductus deferens, which connects the

epididymis to the ejaculatory duct.

• The short ejaculatory duct passes through the prostate

gland and enters the urethra.

• The ductus epididymis consists of

pseudostratified columnar epithelium with long

stereocilia (microvilli).

• The stereocilia do not function in movement, but

function to increase surface area for the

secretion of glycoproteins and the absorption of

fluid released by the testis.

• The glycoproteins function in the process of

spermatozoa maturation; the spermatozoa

become physiologically capable of fertilization of

the egg.

Lab Activity 4 - Epididymis

Lab Activity 4 - Epididymis

Figure 28.15

Scanning power photograph of a section of the epididymis and its

associated testis. The body and tail of the epididymis contains the ductus

epididymis, a long highly convoluted tube.

Figure 28.16

Low power photograph of a section of the epididymis. The body and tail of

the epididymis consists of a long highly coiled tube, the ductus epididymis.

Lab Activity 4 - Epididymis

DUCTUS DEFERENS

The ductus deferens, or vas deferens,

originates from the ductus epididymis

at the tail of the epididymis.

Figure 28.17

High power photograph of a section of the ductus epididymis. Stereocilia

(microvilli) extend from the columnar epithelial cells and function to increase the

surface area for secretion of glycoproteins and absorption of fluid.

9

Ductus (vas) Deferens

• The ductus deferens, or vas deferens, originates from

the ductus epididymis at the tail of the epididymis. It

turns upward to leave the scrotum as a component of the

spermatic cord and enters the abdominal cavity at the

opening of the inguinal canal (ring).

• From here the ductus deferens enters the pelvic cavity

ultimately to pass medially to the seminal vesicle and

downward to the base of the prostate gland.

• At the base of the prostate gland the ductus deferens

merges with the duct from the seminal vesicle to form

the ejaculatory duct, which passes through the prostate

gland and enters the prostatic urethra.

• The ductus deferens functions to transport sperm

from the epididymis to the ejaculatory duct.

Movement of sperm during ejaculation is by

peristaltic waves of the muscularis.

Lab Activity 5 – Ductus (vas)

Deferens

Figure 28.18

Low power photograph of a section of the ductus deferens. The ductus

deferens is a muscular tube with a small lumen. Its muscular layer consists of

smooth muscle which functions in the movement of sperm by peristalsis.

Seminal Vesicles

SEMINAL VESICLES

The two seminal vesicles are

located posterior to the urinary

bladder and anterior to the rectum

Lab Activity 6 – Seminal Vesicles

Figure 28.19

Low power photograph of a section of the seminal vesicle (primate). The

seminal vesicle consists of a highly coiled duct.

• The two seminal vesicles are located posterior to the

urinary bladder and anterior to the rectum. Each is

associated with its respective ductus deferens by way of

an ejaculatory duct formed from the union of the ductus

deferens and the duct from its associated seminal

vesicle.

• A seminal vesicle is formed from a long coiled and highly

branched tube. The posterior end of the tube is a blindend, and anteriorly the tube forms a narrow straight

vesicular duct that joins with its associated ductus

deferens.

• The seminal vesicles function to secrete vesicular

fluid, the major component (about 60%) of semen.

Vesicular fluid is a fructose rich slightly alkaline

fluid.

Lab Activity 6 – Seminal Vesicles

Figure 28.20

Low power photograph of a section of the seminal vesicle (human). This

photograph shows a section of the highly coiled duct. The duct has a secretory

mucosa that is highly branched (diverticula).

10

Lab Activity 6 – Seminal Vesicles

Prostate Gland

Figure 28.21

High power photograph of a section of the seminal vesicle (human). This

photograph shows a section of the mucosa of the highly coiled duct. The secretory

mucosa is highly branched (forms diverticula), which functions to increase its

secretory surface area.

Prostate Gland

• The prostate gland is located inferior to the urinary

bladder at the origin of the urethra (prostatic urethra),

which it completely surrounds.

• Transversing the prostate is the ejaculatory duct, formed

from the union of the ductus deferens and the duct from

its respective seminal vesicle. The prostate is formed

from highly branched glands (tubuloalveolar units), which

merge into ducts that enter the prostatic urethra.

• The highly branched prostatic glands are lined with

columnar epithelium which functions in the secretion of

prostatic fluid. Prostatic fluid comprises about 30% of

semen and is a slightly acid fluid that mostly functions in

the activation of sperm.

• The interstitial tissue (tissue between the glands), or

stroma, consists mostly of smooth muscle and

connective tissue. Contraction of the smooth muscle

during ejaculation moves prostatic fluid into the prostatic

urethra.

Lab Activity 7 – Prostate Gland

Figure 28.23

Low power photograph of a section of the prostate (primate). The glands

(tubuloalveolar units) are lined with columnar epithelium which functions in the

secretion of prostatic fluid.

Lab Activity 7 – Prostate Gland

Figure 28.22

Scanning power photograph of a section of the prostate (primate). The prostate is

composed of glands (tubuloalveolar units) with function in the secretion of prostatic

fluid.

Lab Activity 7 – Prostate Gland

Figure 28.24

High power photograph of a section of the prostate (primate). The glands

(tubuloalveolar units) are lined with columnar epithelium which functions in the

secretion of prostatic fluid. The glands empty into the prostatic urethra.

11

Penis

PENIS

The penis is the copulatory organ of the male

and is formed from three bodies of erectile, or

cavernous, tissue, which are supported by

connective tissue and covered with skin.

Penis

• The three bodies of erectile tissue are the two dorsal

corpora cavernosa and the corpus spongiosum.

• A portion of the penis is internal and forms the root of

the penis. The external portion of the penis is called the

shaft. The single ventral corpus spongiosum houses the

spongy, or penile, urethra. The corpus spongiosum

expands at the tip of the penis to form the glans penis,

the head of the penis.

• The penis is covered with skin, which folds over the

glans penis as the prepuce, or foreskin. The procedure

called circumcision removes the prepuce. The three

bodies of cavernous tissue are each surrounded by

connective tissue called the tunica albuginea.

Penis

• The tunica albuginea surrounding the two dorsal

corpora cavernosa meets in the midline to form

the median septum. The tunica albuginea that

surrounds the corpus spongiosum is thinner

than that surrounding the corpora cavernosa.

• The cavernous tissue is formed from large

vascular areas (sinuses), or cavernous spaces.

Partitions called trabeculae divide the

cavernous spaces which fill with blood

during erection of the penis.

Figure 28.27

The penis is formed from three bodies of erectile, or cavernous tissue that

are supported by connective tissue and covered with skin.

Lab Activity 8 - Penis

Figure 28.28

Scanning power photograph of a section of the human penis. The preparation

shows a portion of the corpus cavernosum, corpus spongiosum, and the urethra.

Lab Activity 8 - Penis

Figure 28.29

Low power photograph of a section of the human penis. The preparation

shows a portion of the corpus spongiosum and the urethra.

12

Lab Activity 8 - Penis

Lab Activity 8 - Penis

Figure 28.30

Low power photograph of a section of the human penis. The preparation

shows a portion of the corpus cavernosum. Increase blood flow into the cavernous

spaces during sexual arousal increases blood pressure within the spaces resulting

in erection. Decreased blood flow allows the elastic and smooth muscle fibers of

the trabeculae to recoil, allowing the penis to become flaccid.

Figure 28.31

Low power photograph of a section of the human penis. The preparation

shows a portion of the corpus cavernosum which has been cleared of blood

during processing of the tissue.

Female Reproductive System

FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE

SYSTEM

The primary sex organs of the

female are the paired ovaries.

Female Reproductive System

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• The ovaries produce hormones and

gametes called eggs (ova).

• Sex hormones produced by the ovaries

include (1) estrogen and (2) progesterone.

• The accessory sex organs, starting with the

ovaries, are the

– (1) uterine tubes (Fallopian tubes, or oviducts),

– (2) uterus, and

– (3) vagina.

Female Reproductive System

The external genitalia (vulva) include the

(1) mons pubis,

(2) labia majora,

(3) labia minora,

(4) vestibule,

(5) clitoris

(6) vestibular glands, and the

(7) paraurethral glands.

Figure 28.32

Illustration of a midsagittal section of the female pelvis.

13

External Genitalia

• Labia majora

– The labia majora are two skin-covered folds of mostly

adipose tissue located inferior to the mons pubis and

form the lateral boundary of the vulva.

EXTERNAL GENITALIA

The external genitalia (or vulva)

are the external genital organs of

the female reproductive system.

• Labia minora

– The labia minora are two skin-covered folds, each

located medially to its respective labium majus. The

labia minora form the lateral boundary of the vestibule

(opening) of the vagina.

• Vestibule

– The vestibule is the chamber, or space, that is formed

within the boundary of the labia minora. Both the

urethra and the vagina open into the vestibule.

External Genitalia

• Clitoris

– The clitoris is a small rounded erectile organ

located at the anterior of the vulva at the

junction of the labia minora. The prepuce of

the clitoris is formed from an extension of the

labia minora.

• Mons pubis

– The mons pubis is an elevated area that

covers the pubic bones. After puberty it is

covered with hair and is usually soft due to

the presence of fat.

External Genitalia

• Greater vestibular glands (Bartholin’s

glands)

– There are two greater vestibular glands. One of each

vestibular gland is located lateral to the vagina and

opens into the vagina’s vestibule.

– The glands produce a mucus lubricating fluid during

intercourse. The greater vestibular glands are

homologous (similar in structure) to the male’s

bulbourethral glands. Several smaller glands called

lesser vestibular glands also open into the vestibule.

• Paraurethral glands

– The paraurethral glands open into the external

orifice (opening) of the urethra and are homologous to

the male’s prostate gland.

Internal Organs

• Broad ligament

INTERNAL ORGANS

– The broad ligament is a double fold of the peritoneum that folds

over and anchors the ovaries, uterine tubes, and uterus. The

broad ligament anchors the uterus to the lateral walls of the

pelvis, and between its two layers of peritoneum the broad

ligament provides a route for the passage of the uterine tubes.

The ovary is attached to the dorsal surface of the broad ligament

near the broad ligament’s lateral merging with the peritoneum of

the pelvis.

• Rectouterine pouch

–

The rectouterine pouch is the area formed between the uterus

and the rectum by the broad ligament.

• Vesicouterine pouch

– The vesicouterine pouch is the area formed between the uterus

and the posterior wall of the bladder by the broad ligament.

14

Internal Organs

• Ovary

Internal Organs

• Ovary

– The paired ovaries are located laterally to the uterus

and are attached to the dorsal surface of the broad

ligament.

– Each ovary is supported and anchored by the

mesovarium, the ovarian ligament, and the

suspensory ligament.

– The ovary is lined with modified visceral peritoneum.

At the margin of the ovary, the visceral peritoneum

changes from simple squamous to simple columnar

epithelium, which covers the ovary as the layer of the

ovary called the germinal epithelium. The germinal

epithelium only functions to structurally line the ovary.

– Internally, the ovary is divided into an outer region

called the cortex and a deep central region called the

medulla.

– Cortex

The cortex of the ovary is the outer region of the

ovary and contains numerous follicles embedded in

a surrounding tissue called the stroma. The follicles

are the sites of oocyte production and maintenance,

and along with the corpus luteum, produce the

primary sex hormones of the female, estrogen and

progesterone. The follicles also release the regulatory

hormone called inhibin.

– Medulla

The medulla of the ovary is the inner central region of

the ovary. The tissue of the medulla, the stroma,

provides a pathway for blood vessels, nerves, etc.

Internal Organs

• Mesovarium

– The mesovarium is a sheet of peritoneum that

attaches the ovary to the lateral wall of the pelvis.

• Ovarian ligament

– The ovarian ligament attaches the medial surface of

the ovary to the lateral wall of the uterus, at a point

just inferior to the entrance of the uterine tube.

• Suspensory ligament

– The suspensory ligament is a fold of peritoneum that

attaches the lateral wall of the ovary to the wall of the

pelvis, and serves as a site for the passage of the

ovarian blood vessels.

Internal Organs

• Uterine tubes (Fallopian tubes or Oviducts)

– Each of the uterine tubes extends from an ovary to the

superior, lateral region of the uterus.

– Extending from the uterus toward the ovary is the

region called the isthmus.

– Near the ovary, they have an expanded region called

the ampulla. The open end of the ampulla is called the

infundibulum.

– Small projections called fimbriae extend from the

infundibulum and drape over the ovary.

Internal Organs

• Uterus

– The uterus is located posterior and superior to the

bladder. It receives the two uterine tubes and serves

as the site for the implantation and development

of the fertilized egg.

• Three major regions are the

– (1) fundus, the rounded portion superior to the

entrances of the uterine tubes.

– (2) body, the central portion of the uterus

– (3) cervix, the narrow portion that projects outward

into the vagina. The cervical canal provides a

pathway from the vagina to the interior cavity of the

uterus.

Internal Organs

Uterine wall

• The three layers of the wall of the uterus are,

from the outside inward, the

– (1) perimetrium, the serous membrane that covers the

outside of the uterus

– (2) myometrium, the thick middle smooth muscle

layer

– (3) endometrium, the inner layer that undergoes cyclic

changes in response to ovarian hormones. The

endometrium is divided into the stratum functionalis

and the stratum basalis.

Vagina

– The vagina is the tubular organ that extends from the

cervix to the exterior region called the vestibule. It

serves as a passageway for the delivery of a baby

and receives the penis during sexual intercourse.

15

Internal Organs

OVARY

The paired ovaries are located laterally

to the uterus and are attached to the

dorsal surface of the broad ligament.

Figure 28.33

Anterior view of the uterus and associated organs.

Ovary

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

• The paired ovaries are located laterally to the

uterus and are attached to the dorsal surface of

the broad ligament. The ovary is lined with

modified visceral peritoneum called the germinal

epithelium.

• The germinal epithelium functions as a lining of

the ovary. Internally, the ovary is divided into an

outer region called the cortex and a deep

central region called the medulla.

– The cortex of the ovary is the outer region of the

ovary and contains numerous follicles embedded in a

surrounding tissue called the stroma.

– The medulla of the ovary is the inner central region of

the ovary. The tissue of the medulla, the stroma,

provides a pathway for blood vessels, nerves, etc.

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

Figure 28.34

Scanning power photograph of an ovary (monkey). Numerous follicles are

observed in the cortex.

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

Primordial follicles

Primordial follicles are

located toward the

periphery of the cortex.

Each primordial follicle

consists of a primary

oocyte that is surrounded

by a single layer of

squamous cells called

follicular cells.

Figure 28.35

Low power photograph of the cortex of an ovary (monkey). Three types of

follicles can be observed, primordial, primary, and secondary follicles.

Figure 28.36

High power photograph of primordial follicles (monkey ovary).

16

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

Primary follicles

Primary follicles

develop from

primordial follicles.

Each primary follicle

consists of a primary

oocyte that is

surrounded by several

layers of cuboidal cells

called granulosa cells.

Figure 28.37

High power photograph of primary follicles (monkey ovary).

Secondary follicles (tertiary,

vesicular, or Graafian)

Secondary follicles (tertiary,

vesicular, or Graafian)

• Secondary follicles develop from primary

follicles.

• The secondary follicle consists of an oocyte

surrounded by several layers of granulosa cells

that produce a fluid-filled central cavity called the

antrum.

• A layer of granulosa cells, the corona radiata,

surrounds the oocyte and the region of

glycoproteins, the zona pellucida. The zona

pellucida is a glycoprotein matrix with microvilli,

microvilli of the granulosa cells and microvilli of

the oocyte. The microvilli allow for the exchange

of materials between the primary oocyte and the

granulosa cells.

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

• Upon ovulation, the secondary oocyte and its

associated zona pellucida and corona radiata

are discharged from the mature secondary

follicle.

• A mature secondary follicle that is ready to

rupture in ovulation is referred to as a vesicular

(Graafian) follicle. After ovulation, the vesicular

follicle is transformed into an endocrine organ,

the corpus luteum.

Figure 28.38

High power photograph of an early secondary follicle (monkey ovary).

Lab Activity 9 - Ovary

CORPUS LUTEUM

The corpus luteum develops from

the ruptured vesicular (or

Graafian) follicle after ovulation

Figure 28.39

High power photograph of a late secondary follicle (monkey ovary). Secondary

follicles are also called vesicular, tertiary, or Graafian follicles.

17

Corpus Luteum

• The corpus luteum develops from the ruptured vesicular

(or Graafian) follicle after ovulation.

• The corpus luteum functions as an endocrine gland and

produces progesterone (mostly) and estrogen.

• Hormone producing cells are the theca and granulosa

lutein cells. The theca is the outer covering of the

Graafian follicle. Some of its cell, the theca lutein cells

produce estrogen. The granulosa cells develop into

granulosa lutein cells and produce progesterone.

• If an embryo implants, a hormone is produced by the

developing placenta that maintains the corpus luteum. If

an embryo does not develop, the corpus luteum begins

to degenerate, and its hormonal functions are terminated

by the time of menstruation. The corpus luteum

degenerates into the corpus albicans.

Lab Activity 10 – Corpus Luteum

Figure 28.41

Scanning power photograph of the corpus luteum (monkey ovary). This

corpus luteum is relatively late in development as the lutein cells, which develop

from the granulosa cells, have completely filled the prior location of the antrum.

Lab Activity 10 – Corpus Luteum

Figure 28.40

Scanning power photograph of the corpus luteum. This corpus luteum is relatively

early in development as the lutein cells, which develop from the granulosa cells,

have not completely filled the prior location of the antrum.

Lab Activity 10 – Corpus Luteum

Figure 28.42

High power photograph of the corpus luteum (monkey ovary). The

progesterone-secreting cells of the corpus luteum are the lutein cells which

develop from the granulosa cells of the follicles.

Lab Activity 11 – Corpus Albicans

CORPUS ALBICANS

The corpus albicans is the fibrous

connective tissue that develops as a

result of the degeneration and

reabsorption of the corpus luteum.

Figure 28.43

Scanning power photograph of the corpus albicans (monkey ovary). The corpus

albicans is usually pale-stained as it consists mostly of fibrous connective tissue.

18

Lab Activity 11 – Corpus Albicans

MEIOSIS - OOGENESIS

Oogenesis is the process of

production and maturation of the

egg (ovum).

Figure 28.44

High power photograph of the corpus albicans (monkey ovary). The

pale-stained corpus albicans consists mostly of fibrous connective tissue.

Meiosis and Oogenesis

• Oogenesis is the process of production and

maturation of the egg (ovum).

• Oogenesis begins in early fetal development

with the mitotic production of oogonia (2n), the

precursor (stem) cells to the ova.

• The oogonia develop into primary oocytes as

they become surrounded by a single layer of

follicular cells, forming a primordial follicle.

Meiosis and Oogenesis

• A primary oocyte (2n) completes meiosis I to produce

two cells of very unequal size. The smaller of the two

cells is called the first polar body. The larger secondary

oocyte (n), which received most of the cytoplasm,

continues with meiosis II until metaphase II and then

stops.

• The secondary oocyte in metaphase II is ovulated. If

fertilization occurs, the secondary oocyte finishes

meiosis II. It produces a second polar body and an ovum

(n), or mature egg.

• Nuclear union between the ovum and sperm

produces a diploid (2n) zygote. The second polar

body, as with the other two second polar bodies

produced by meiosis II of the first polar body,

degenerates.

Meiosis and Oogenesis

• The primary oocytes enter meiosis I, which quickly

stops in prophase I. At birth and until puberty, the ovary

contains several million primary oocytes, each in a

primordial follicle.

• At puberty and mostly under the influence of

gonadotropic hormones (mostly follicle stimulating

hormone, FSH) cyclically released from the anterior

pituitary, some hormone sensitive primordial follicles

begin to develop. The primary oocyte continues with

meiosis I, and the single layer of follicular cells develops

into layers of cells, the granulosa cells, forming a

primary follicle.

Meiosis and Oogenesis

Figure 28.45

Oogenesis is the process of female gamete production. Meiosis reduces

the diploid human chromosome number of 46 to the haploid number of 23. Meiosis

assures that the ovum contains only half of the homologous chromosomes.

19

Lab Activity 12 – Oogenesis

Figure 28.46

Ovary (human) of a infant. Primary oocytes are produced early in fetal

development and their meiotic activity stops in prophase I. The primary oocytes are

surrounded by a single layer of follicular cells. A primary oocyte and its follicular

cells are called a primordial follicle. Primordial follicles remain inactive until the

onset of puberty.

Lab Activity 12 – Oogenesis

Figure 28.47

Ovary (monkey) showing various stages of oocyte and follicular development.

Lab Activity 12 – Oogenesis

OVARIAN CYCLE

Figure 28.48

Primordial follicles. Each primordial follicle consists of a single layer of follicular cells

and a primary oocyte. It is estimated that at birth each ovary contains up to

2,000,000 primordial follicles.

The ovarian cycle is the approximate 28 days

(monthly) sequence of changes that occur in

the ovary in relation to its follicular

development, ovulation, and development of

the corpus luteum

Ovarian Cycle

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

The ovarian cycle is the approximate 28

days (monthly) sequence of changes that occur

in the ovary in relation to its follicular

development, ovulation, and development of the

corpus luteum.

• The cycle of the ovary is regulated by the two

gonadotropic hormones (released from the

anterior pituitary (pars distalis) called follicle

stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing

hormone (LH), and by negative feedback from

three hormones, estrogen, progesterone, and

inhibin.

• Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is

produced and released from the anterior

pituitary gland (pars distalis).

• Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) targets

the follicles of the ovaries to stimulate

follicular development. Developing

follicles under the influence of FSH

release the regulatory hormone inhibin

and mostly the sex hormone estrogen.

•

20

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

• A negative feedback mechanism controls the

secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

– Increased levels of inhibin result in hypothalamic

reduction of gonadotropin-releasing hormone

(GnRH), which results in a reduction of folliclestimulating hormone (FSH);

– decreased levels of inhibin result in hypothalamic

increase of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH),

which results in an increase of follicle-stimulating

hormone (FSH).

Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

• Luteinizing hormone (LH) is produced and

released from the anterior pituitary (pars

distalis).

• Luteinizing hormone (LH) targets

– (1) the mature follicle of the ovary to trigger

ovulation,

– (2) and promotes the development of the

corpus luteum, which secretes estrogen and

progesterone.

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH)

Figure 28.49

Follicle-stimulating hormone

(FSH) is produced and

released from the anterior

pituitary gland (pars distalis).

Follicle-stimulating hormone

(FSH) targets the follicles and

promotes their development.

Developing follicles release

inhibin which results in the

reduction of GnRH, thus

reducing FSH.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

• A negative feedback mechanism controls the

secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH).

• Increased levels of estrogen and progesterone

result in hypothalamic reduction of

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which

result in a decrease of luteinizing hormone (LH);

• Decreased levels of estrogen and progesterone

result in hypothalamic increase of gonadotropinreleasing hormone (GnRH), which results in an

increase of luteinizing hormone (LH).

Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

Figure 28.50

Luteinizing hormone (LH) is produced

and released from the pars distalis.

For females, luteinizing hormone (LH)

targets the mature follicle, and

supports corpus luteum and

secretion of estrogen and

progesterone.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

The ovarian cycle is divided

into the follicular phase and the

luteal phase.

21

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Phases of Uterine Cycle

• Follicular phase

– The follicular phase of the ovarian cycle is the

time of follicular development,

approximately days 1 - 14, with day 14 as the

day of ovulation.

• Luteal phase

– The luteal phase of the ovarian cycle is the

time following ovulation, approximately days

14 - 28, when the corpus luteum develops

and is maintained.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.52

Photographs of the structures of an ovarian cycle. During the ovarian cycle

follicles develop (follicular phase), ovulation occurs, and the corpus luteum

develops (luteal phase). A corpus albicans, a body of fibrous tissue forms from

the degeneration of the corpus luteum.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.54

Photographs of primary and secondary follicles of the ovary (monkey). Primary

follicles are developing follicles. Their granulosa and theca cells secrete

estrogen. As the number and size of the granulosa and theca cells increases so

does the level of estrogen. Primary follicles develop into secondary follicles.

Figure 28.51

Illustration showing the sequences of changes in the 28 day ovarian

cycle. The follicular phase (days 1 - 14) is the preovulatory phase and is the time

of follicular development. The luteal phase (days 14 - 28) is the postovulatory

phase and is the time of the development of the corpus luteum.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.53

Photographs of primordial and primary follicles of the ovary (monkey). Primordial

follicles receptive to follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) released by the

anterior pituitary gland develop into primary follicles.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.55

Photographs of an early secondary and a late secondary follicle of the ovary

(monkey). Secondary follicles secrete increasing amounts of estrogen as their

granulosa and theca cells increase in size and number. A late secondary

follicle develops into a vesicular (Graafian) follicle.

22

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.56

Photograph of an early secondary follicle (monkey ovary) and an illustration of

ovulation. At ovulation the follicular phase ends, and the luteal phase begins

with the conversion of the vesicular follicle of ovulation into an endocrine

gland called the corpus luteum.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.57

Illustration of a vesicular follicle of ovulation and a photograph of the corpus luteum

(monkey ovary). The corpus luteum functions as an endocrine gland and

secretes progesterone and estrogen.

Phases of Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.58

Photographs of the corpus luteum and the corpus albicans (monkey ovary). The

corpus albicans consists of fibrous connective tissue that develops from the

degeneration of the corpus luteum.

Figure 28.59

Illustration of the ovarian cycle. The cycle of the ovary is regulated by the two

gonadotropic hormones released from the anterior pituitary (pars distalis), follicle

stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), and by negative

feedback from three hormones, estrogen, progesterone, and inhibin.

Uterine Tube

UTERINE TUBE

The uterine tube (also called oviduct,

or Fallopian tube) is the tube that

extends between the ovary and the

uterus

• The uterine tube (also called oviduct, or

Fallopian tube) is the tube that extends

between the ovary and the uterus.

• Each of the two uterine tubes is divided

into three regions,

– (1) isthmus,

– (2) ampulla, and

– (3) infundibulum.

23

Lab Activity 13 – Uterine Tube

Lab Activity 13 – Uterine Tube

Figure 28.62

Low power photograph of the ampulla’s wall. The highly folded mucosa extends

into the lumen of the uterine tube.

Figure 28.61

Scanning power photograph of the isthmus of the uterine tube.

Lab Activity 13 – Uterine Tube

UTERUS

Figure 28.63

High power photograph of the mucosa of the ampulla of the uterine tube. The

highly folded mucosa is lined with ciliated columnar cells. Numerous secretory

cells are found among the ciliated cells.

Uterus

The uterus is the organ that functions

as the site for the development of the

embryo and fetus prior to birth.

Uterus

• The uterus is located in the pelvic cavity

between the urinary bladder and the rectum.

• The uterine tubes open into its superior-lateral

body.

• The cervix of the uterus opens into the inferior

vagina.

• The uterus is the organ that functions as the

site for the development of the embryo and

fetus prior to birth.

Figure 28.64

The uterus is the organ that functions as the site for the development

of the embryo and fetus prior to birth.

24

Uterus

Uterus

• Isthmus

• Fundus

– The fundus of the uterus is the superior

portion of the uterus, the region above the

points of attachment of the uterine tubes.

• Body

– The body of the uterus is the region between

the superior fundus and the inferior isthmus

– The isthmus of the uterus is a narrow constricted

region inferior to and continuous with the body. The

uterine cavity of the uterus narrows to form the

internal orifice at the superior internal boundary of

the isthmus.

• Cervix

– The cervix of the uterus is the most inferior

portion of the uterus.

– The cervix is continuous with the isthmus and its

inferior surface curves outward into the vagina.

– The opening into the cervix is called the external

orifice (or cervical os). The external orifice opens into

the cervical canal, which leads to the internal orifice.

The internal orifice is continuous with the uterine

cavity.

Uterine Wall

• Perimetrium

– The perimetrium is the serous membrane, the peritoneum, which

covers the fundus and the anterior-posterior surfaces of the

uterus.

UTERINE WALL

• Myometrium

– The myometrium is the thick middle muscularis of the uterus.

• Endometrium

The wall of the uterus consists of three

layers, from the outside inward, the

layers are the (1) perimetrium, (2)

myometrium, and (3) endometrium.

Uterine Wall

– The endometrium is the inner mucosa of the uterus and consists

of two layers the (1) stratum functionalis and the (2) stratum

basalis. The endometrium undergoes cyclic changes, the

uterine cycle, in response to ovarian hormones.

– The endometrium consists of numerous uterine (endometrial)

glands and blood vessels located within a layer of connective

tissue, the stroma.

Uterine Wall

• Uterine glands

– Uterine glands are the tubular glands of the mucosa

(endometrium) of the uterus. Early in the uterine cycle the uterine

glands are small and relative straight. Under the influence of

increased estrogen and progesterone, the uterine glands but

become enlarged, contorted, and sacculated (having small

lateral branches). Uterine glands function in the secretion of

nutrient rich mucus fluid.

• Blood vessels - spiral arteries

– The blood vessels that deliver blood to the endometrium are the

spiral arteries. The development of the spiral arteries is

under hormonal control. Their growth is promoted by

increased estrogen and progesterone levels. Atrophy of the

spiral arteries occurs when levels of estrogen and progesterone

become low.

• Stroma

– The stroma is the connective tissue that forms the framework

of the endometrium, it contains the spiral arteries and the uterine

glands.

Figure 28.65

The endometrium is the inner mucosa of the uterus. It contains numerous uterine

(endometrial) glands and blood vessels located within connective tissue called the

stroma. The mucosa is located interior to the muscularis, the myometrium.

25

Endometrium

• Stratum basalis

– The stratum basalis is the layer of the

endometrium close to the muscularis. The

stratum basalis is the permanent layer of the

endometrium. Uterine glands and blood

vessels are maintained in the stratum basalis.

• Stratum functionalis

– The stratum functionalis is the layer of the

endometrium closest to the uterine cavity and

undergoes modifications in preparation of

implantation of the fertilized egg.

Uterine Cycle

• The uterine (menstrual) cycle is divided

into three phases, the (1) menstrual

phase, (2) proliferative phase, and (3)

secretory phase.

• During the cycle the stratum functionalis,

in response to changing levels of estrogen

and progesterone, undergoes

considerable structural changes.

Uterine Cycle

• Proliferative phase

– The proliferative phase begins the rebuilding

of the stratum functionalis. The proliferative

phase begins in response to increasing

levels of estrogen from the developing

follicles (granulosa cells) of the ovary.

Uterine Cycle

The uterine (menstrual) cycle is divided into three

phases, the

(1) menstrual phase,

(2) proliferative phase, and

(3) secretory phase.

Uterine Cycle

• Menstrual Cycle

– The menstrual cycle is the complete cycle of the

uterus (of approximately 28 days) from one menstrual

period to the next.

• Menstrual phase (period)

– The menstrual period is the time in the menstrual

cycle in which menses, the flow of menstrual fluid,

occurs.

– The menstrual period occurs when levels of estrogen

and progesterone are at their lowest, and is

characterized by the shedding of the existing

developed stratum functionalis.

– This phase corresponds to the ending of the luteal

phase of the ovarian cycle characterized by the

degeneration of the corpus luteum with the reduction

of progesterone (and estrogen) levels.

Uterine Cycle

• Secretory phase

– The secretory phase continues the rebuilding with

additional preparations such as the secretion of

glycoproteins for receiving the fertilized egg.

– The secretory phase is enhanced by increased

levels of progesterone and estrogen. Progesterone

and estrogen levels increase from the development of

the corpus luteum following ovulation.

– If implantation does not occur, the corpus luteum

degenerates resulting in reduced levels of

progesterone and estrogen. With reduced levels of

hormones, the next uterine cycle begins with the

menstrual phase. The menstrual phase results in the

removal of the developed stratum functionalis.

– If implantation occurs, the corpus luteum is

maintained for a short time and the uterus continues

to develop as the uterus of pregnancy and supports

the developing embryo and fetus.

26

Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.66

The uterine (menstrual) cycle is divided into three phases, the (1) menstrual phase,

(2) proliferative phase, and (3) secretory phase. During the cycle the stratum

functionalis, in response to changing levels of estrogen and progesterone, undergoes

considerable structural changes.

Lab Activity 14 –

Menstrual Phase

Figure 28.68

Scanning power photograph of the menstrual phase of the uterus. The

endometrium is thin, and the stroma and uterine glands are filled with blood from

ruptured blood vessels.

Uterine Cycle

Figure 28.67

Photographs of the phases of the uterus

(human). The uterine cycle is divided into

three phases, the (1) menstrual phase

(menses), (2) proliferative phase, and (3)

secretory phase. The phases may be

further divided into early and late.

A Menstrual Phase, Days 1 - 4

B Proliferative Phase, Days 4 - 14

C Early Secretory Phase, Days 14 - 18

D Secretory Phase, Days 18 - 23

E Secretory Phase, Days 23 - 25

F Late Secretory Phase, Days 25 - 28

G Pregnant uterus

Lab Activity 15 –

Proliferative Phase

Figure 28.70

Scanning power photograph of the proliferative phase of the uterus (human),

days 4-14. The uterine glands are observed as tubes with slight convolutions.

Lab Activity 16 –

Secretory Phase

VAGINA

The vagina is located between the

cervix of the uterus and the opens at

the external region between the labia

minora, the vestibule

Figure 28.71

Scanning power photograph of the late secretory phase of the uterus

(human), days 23-25. The uterine glands are large and highly coiled with

sacculations.

27

Vagina

The vagina is located between the cervix of

the uterus and the opens at the external region

between the labia minora, the vestibule.

• The vagina functions to receive the penis

during intercourse and serves as the lower

part of the birth canal.

• The inner layer of the wall of the vagina is the

mucosa and is lined with non-keratinized

stratified squamous epithelium. The middle

muscularis of the vagina is composed of circular

and longitudinal layers of smooth muscle.

Lab Activity 17 – Vagina

•

Figure 28.72

Scanning power photograph of the vagina (human). The inner layer of the

vagina, the mucosa, is lined by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

The muscularis consists of smooth muscle, an inner circular and an outer

longitudinal layer.

Lab Activity 17 – Vagina

MAMMARY GLANDS

Figure 28.73

Low power photograph of the stratified squamous epithelium of the mucosa.

Mammary Glands

• The paired mammary glands (commonly called

breasts) are modified sebaceous glands that

function in the production of milk, or lactation.

• They are located within the superficial fascia on

the anterior sides of the chest. Each mammary

gland is associated with a protuberance called a

nipple.

• A nipple contains ducts from the glandular

tissue that transport milk to the outside. Around

each nipple is a pigmented area called the

areola.

The paired mammary glands (commonly

called breasts) are modified sebaceous

glands that function in the production of milk,

or lactation.

Mammary Glands

• Mammary glands consist of glandular tissue surrounded

and organized by fibrous connective tissue and fat.

• The glandular tissue is organized into lobes, which are

subdivided into lobules. The secretory units of the

lobules are called alveoli, sacs of cells that are found at

the terminal ends of excretory ducts.

• The excretory ducts of the alveoli merge into small

lacteriferous ducts. The lacteriferous ducts continue to

merge and form a large lacteriferous duct for each lobe

(glandular unit). The lacteriferous ducts converge to the

base of the nipple and each expands to form a

lacteriferous sinus.

• The lacteriferous sinuses enter the nipple and open to

the outside.

28

Mammary Glands

Mammary Glands

• During pregnancy the primary hormones for the

development of the mammary glands include

estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin.

– Prolactin, secreted from the anterior pituitary is the

primary hormone for the production of milk.

– Milk is not produced prior to birth because estrogen

and progesterone have an inhibitory effect on

prolactin. However, following birth estrogen and

progesterone levels decrease and their inhibitory

effect on prolactin is removed.

Figure 28.74

Mammary glands consists of glandular tissue surrounded and organized by

fibrous connective tissue and fat. The glandular tissue is organized into lobes, which

are subdivided into lobules. Each lobe is associated with a lactiferous duct, which

expands near the nipple into a lacteriferous sinus.

Mammary Glands

Lab Activity 18 –

Active Mammary Glands

• Mammary glands that are hormonally

stimulated during pregnancy undergo

increased glandular development.

• The lobules, undergo dramatic increases

in the production and size of their

secretory units, the alveoli.

• Thus, mammary glands are described as

active and inactive by the degree of

glandular development and activity.

Figure 28.75

Low power photograph of the well developed lobules of an active mammary gland.

The secretory units of the lobules are called alveoli.

Lab Activity 18 –

Active Mammary Glands

Figure 28.76

High power photograph of a lobule of an active mammary gland showing the

secretory units called alveoli.

Lab Activity 19 –

Inactive Mammary Glands

Figure 28.77

Low power photograph of the lobules of an inactive mammary gland. The

connective tissue between the lobules, the interlobular septa, and associated fat

appear abundant because of the reduced size of the alveoli.

29