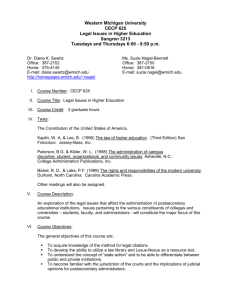

preliminary injunctions, and stays pending

advertisement