RECIPROCITY IN MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS A Dissertation

RECIPROCITY IN MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS

A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School

University of Missouri

In Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy by

DONALD J. LUND

Dr. Lisa Scheer, Dissertation Supervisor

DECEMBER 2010

This dissertation is dedicated to my family.

To my children, I’m sorry that I’ve missed out on much during the last few years. Thank you for understanding. Very few people know the sacrifices you have made.

To my mom, I wish you could be here in person for me to thank for all of your support, love and caring throughout my life. I know you have always been with me, and I will never forget you.

To my father, I hope that you have stopped trying to make up for whatever it was you were supposed to do while I was in college – because I am honestly done with school now! Your encouragement, support, and guidance have been invaluable. You have helped make me the man I am. And how could I forget: Doctor, Dentist or Lawyer!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my dissertation committee, Detelina Marinova, Chris

Groening and Peter Klein for all of their help, guidance and time during the creation, revision and completion of this dissertation. Each of you offered a unique perspective throughout the entire process that helped make this a better project. I will be forever grateful for your time and interest in helping make this process a success. Additionally I would like to thank Thomas Rose, Karen Nazario and Laurel Youmans for their help in navigating the dissertation process at the University of Missouri.

I would especially like to thank my dissertation chair, Lisa Scheer, for her the extensive amount of time she put in to improving my experience during my four years at the University of Missouri. Lisa helped me by focusing on professional development, academic rigor, career planning, and managing my personal life. I could not have asked for a better mentor for this process. I look forward to being able to earn the peer status you have already begun to treat me with.

I would also like to thank a few organizations that made my dissertation financially possible; the Robert J. Trulaske, Sr. College of Business provided financial support for a number of conference presentations, statistical software, and for my PhD program in general. Additional funding that helped pay for survey printing and postage was provided by Professor Lisa Scheer’s Emma S. Hibbs Professorship. Finally, Boone

County National Bank provided financial support for printing and postage of a survey for ii

this research. Without the financial support acknowledged above, this research would not have been able to be completed.

I feel lucky and blessed to have chosen the University of Missouri for my doctoral program. The faculty, staff, administration and students all combined to build an environment that has allowed me to develop and grow. I have no doubt that my training is far superior to my expectations when considering different programs for my

PhD. iii

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 3: A GENERAL THEORY OF EPISODIC RECIPROCITY IN MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS ... 21

i v

CHAPTER 5: RELATIONAL RECIPROCITY IN MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS: THE ROLE OF COMPLEX

v

v i

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Page

1.

The Domain of Marketing Interactions ........................................................................ 12

2.

Positive Reciprocal Debt Responses ............................................................................ 30

3.

Negative Reciprocal Debt Responses .......................................................................... 33

4.

Dependence Configurations ........................................................................................ 45

5.

Process Model of Positive Reciprocity ......................................................................... 49

6.

Process Model of Negative Reciprocity ....................................................................... 50

7.

Process Model of Reciprocity ...................................................................................... 51

8.

Random Assignment to Beneficial Conditions ............................................................. 52

9.

Random Assignment to Detrimental Conditions ......................................................... 52

10.

Plots of mean differences in OwnOut and RO based on the Valence manipulation ......................................................................................... 75

11.

Plots of mean differences in automaker and other based on the attribution manipulation ............................................................................... 76

12.

Scatterplot of RDLocus per OwnOut ............................................................................ 80

13.

Estimated Marginal Means of RDLocus ....................................................................... 83

14.

Experimental Research Model Tested ......................................................................... 88

15.

Experimental Process Flowchart .................................................................................. 89

16.

Random Assignment to Conditions ............................................................................. 90

17.

Manipulations: Partner’s Initial Allocation Offer ........................................................ 92

18.

Conceptual Framework for Beneficial Actions ............................................................ 103 v i i

19.

Conceptual Framework for Detrimental Actions ......................................................... 103

20.

Impact of Valence on Locus (ANOVA) .......................................................................... 104

21.

Locus*Valence Crosstabulation ................................................................................... 106

22.

Locus*Magnitude Crosstabulation .............................................................................. 106

23.

ANOVA Results of PartnerOut at Different Locus ........................................................ 112

24.

ANOVA Results for Positive Norm of Reciprocity’s

Impact on RD and RDLocus ....................................................................................... 119

25.

Plots of RD based on Perceived Impact and the Positive

Norm of Reciprocity .................................................................................................. 119

26.

ANOVA Plots of NR on RD and RDLocus ...................................................................... 120

27.

Moderating Impact of Negative Norm of Reciprocity ................................................. 122

28.

ANOVA Plot of the moderating impact of PR .............................................................. 124

29.

Relational Reciprocity Conceptual Framework............................................................ 145

30.

Final Structural Model – Significant Paths ................................................................... 167 v i ii

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1.

Reciprocity Definitions in Marketing Interpersonal Relationships .............................. 5

2.

Reciprocity Definitions in Marketing B2B Relationships ............................................. 6

3.

Approaches to Reciprocity taken in Seminal Works .................................................... 20

4.

Experimental Scenario Components ........................................................................... 57

5.

Recruitment Regions .................................................................................................... 61

6.

Summary of Individual EFA’s for 4 Latent Constructs ................................................. 64

7.

Separate EFA on RD and Just ....................................................................................... 64

8.

Overall Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for Study Variables ................ 65

9.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for Participants in the Beneficial Condition ............................................................................................ 67

10.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for Participants in the Detrimental Condition ........................................................................................ 67

11.

CFA Results ................................................................................................................... 72

12.

ANOVA results for OwnOut and RO Valence manipulation checks ............................. 74

13.

12a. ANOVA results for automaker and other – attribution manipulation checks ..... 76

14.

Mean difference in Locus based on valence manipulation ......................................... 78

15.

Coefficients from regression of Locus on manipulation factors .................................. 78

16.

Coefficients from regression of RDLocus on OwnOut ................................................. 80

17.

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ............................................................................... 82

18.

Planned Contrast Results (K Matrix) Justifiability ........................................................ 83 i x

19.

Test Results for planned contrast ................................................................................ 83

20.

Car Dealer Survey Hypothesis Summary ..................................................................... 84

21.

Combined EFA on 4 Latent Constructs ........................................................................ 97

22.

Summary of Individual EFA’s for 4 Latent Constructs ................................................. 98

23.

CFA Results ................................................................................................................... 100

24.

ANOVA’s with the Valence manipulation as the Independent variable ...................... 101

25.

ANOVA’s with the Magnitude manipulation as the independent variable ................. 102

26.

General Linear Model Test of Mean Differences ......................................................... 105

27.

Parameter Estimates .................................................................................................... 107

28.

Classification Results of Multinomial Regression for Locus ......................................... 107

29.

Spline Regression Results ............................................................................................ 109

30.

Spline Regression Results with no Intercept ............................................................... 110

31.

Contrast Coefficients ................................................................................................... 112

32.

Contrast Tests .............................................................................................................. 112

33.

Spline Regression for RDLocus effect on PartnerOut .................................................. 113

34.

Spline Regression for the moderating impact of relative outcomes ........................... 115

35.

Regression of PR and OwnImpact on RDLocus ............................................................ 116

36.

Regression of OwnImpact and PROwnImpact on RDLocus ......................................... 117

37.

Norm of Positive Reciprocity’s effect on Reciprocal Debt (ANOVA) ........................... 117

38.

Between-Subjects Factors ........................................................................................... 118

39.

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ............................................................................... 118 x

40.

ANOVA results for Negative Norm of Reciprocity’s impact on RD and RDLocus ................................................................................................... 120

31.

Between-Subjects Factors ........................................................................................... 121

32.

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ............................................................................... 121

33.

Between-Subjects Factors ........................................................................................... 122

34.

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects ............................................................................... 123

35.

Experimental Research Hypothesis Summary ............................................................. 124

36.

Dimensions of Complex and Simple Reciprocity ......................................................... 135

37.

Antecedent Variables EFA ............................................................................................ 156

38.

EFA for Relational Reciprocity ...................................................................................... 157

39.

Outcome variable EFA Results ..................................................................................... 158

40.

Overall CFA results for all items in the theoretical model ........................................... 162

41.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations Between Study Variables ................... 163

42.

Structural Model Results ............................................................................................. 165

43.

Mediation Analyses for the Structural Path Model ..................................................... 168 x i

RECIPROCITY IN MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS

Donald J. Lund

Dr. Lisa Scheer, Dissertation Supervisor

ABSTRACT

Marketing researchers have often cited reciprocity as an important aspect of relational exchange; however the extant research has not conceptualized or measured reciprocity in marketing relationships. This research is a first attempt to explicate the role of reciprocity in these exchange relationships. Reciprocity is first conceptualized as a component of discrete transactions. A theoretical model is built and tested in (a) a laboratory setting and (b) through a survey of car dealership managers. The role of reciprocal debt is established and shown to impact exchange relationships. Next, reciprocity is conceptualized as a multidimensional element of ongoing exchange relationships. Through a survey of business customers of a bank, the existence of relational reciprocity is established and shown to impact numerous indicators of relationship success. Implications for both theory and practitioners are presented, and future research directions are discussed. x i i

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Reciprocity in Marketing Theory

“I regard reciprocity as an essential feature of self-regulation and the problem of coordinating mutual actions for parties in a marketing relationship.”(Bagozzi 1995)

Marketing as a discipline has failed to adequately incorporate the concept of reciprocity in any theory of customer relationships. The term reciprocity appears in much of the marketing literature, especially those streams focusing on relationship marketing (both consumer and

B2B), however very few researchers have attempted to conceptualize or measure reciprocity at all. Reciprocity research within marketing can be categorized as two distinct types. The first is explicit-reciprocity research, where the researchers attempted to measure reciprocity and/or offer a specific definition, and subsequently place it into their conceptual framework and/or hypotheses. The second category is implicit-reciprocity research, where the term reciprocity is used, but is not measured nor explicitly defined. The former section is minute compared to the latter. The following is an overview of the explicit marketing reciprocity research. This research can be segregated depending on the focus of the reciprocal interaction – interpersonal versus interorganizational.

1.1.1 Reciprocity in Interpersonal Relationships

The earliest explicit use of reciprocity located in the marketing literature drew almost exclusively from legal cases. Moyer (1970) discusses “Reciprocal Buying” and describes reciprocity as doing business with one’s friends (see definition in table #1). “You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours” (p. 47). The focus of this line of research was on coercive reciprocity, where partner A threatens reduced purchasing if partner B didn’t increase or maintain purchase levels from A. Relationships like that described above led to the development of anti-trust laws to attempt to prevent “strong-arming”, and the potential harm it

1

could have on consumers (not to mention the less powerful partner). Finney (1978) later did a follow up intending to examine if this coercive type of reciprocity continued to exist in businesses. Finney found that although it probably continued to occur in some relationships, the prevalence had decreased substantially since Moyer’s research in 1970. This concept of reciprocal buying points out an important fact about reciprocal behavior: it has the potential to influence the behavior of a relational partner. This is reminiscent of Howard Becker’s description of the role of reciprocity in the social learning process. Do marketing relationships exhibit goal oriented (positive or negative) reciprocal behavior intended to mold the response of their partner?

Houston and Gassenheimer (1987) extend the conceptual work of Bagozzi (1975) in developing exchange theory as the key component of marketing. Houston and Gassenheimer argue that an exchange relationship is created when “…one party is expected to defer receipt of value into the future…” (p. 10). They go on to explain the role of reciprocity in exchange relationships in great detail, arguing that reciprocity is present in every exchange relationship, and that its implementation varies depending on the “social distance” of the parties involved.

While they do not define social distance, it appears that minimum social distance is implied by a familial relationship, intermediate would involve friendships and business relationships, and maximum social distance is presumably strangers. Interestingly, Houston and Gassenheimer theorize that negative reciprocity is only engaged in with strangers, citing an example of bribery.

Additionally, they suggest that with a minimum social distance (e.g. parental relationships), partners give willingly, “the value to A being in the giving of the product”, which is more in line with altruistic behavior when no expectation of future return of benefits exists. More recent work has interpreted the parent-child relationship differently, suggesting that the level of lateadult healthcare provided by the child may depend on child perceptions of parental investments

2

during the child’s youth, suggesting that altruism may not be the only explanation of this type of giving. While this paper does not specifically measure reciprocity, the authors do offer a definition and explicitly place reciprocity as a functional component of exchange relationships

(see Table #1).

Marketing researchers have approached reciprocity from both a consumer perspective, as well as from an interorganizational perspective. Dawson (1988) found that reciprocal motivations were one of four motivations for consumer charitable giving. His definition of reciprocity (see Table #1) could potentially be applied to any plausible exchange being that it only encompasses a future benefit expectation from a donor. The measures used to capture reciprocity focused on past benefits received (by the donor or their family) and on the expected benefits to be gained by the donor from the charitable organization in the future. Frenzen and

Davis (1990) find that existing “social debts” increased the likelihood of purchase in socially embedded markets (e.g. Mary Kay sales parties among friends). After controlling for the economic utility of purchases made, they found that attendees at sales parties were more likely to purchase from a host who had previously purchased from them. Miller and Kean (1997) find that when local business owners exhibit interpersonal reciprocity (defined as emphasizing concern for others or strong attachment to others), rural consumers are more likely to behave reciprocally by purchasing locally. As we can see by this approach, the focus of reciprocity is on cooperation, a concept that is definitely related to, but not the same as, reciprocity. In a consumer-retailer exchange, Dahl, Honea and Manchanda (2005) find that consumers may experience guilt if they are not able to reciprocate the social interaction (through a purchase).

Subsequently, they are more likely to return and purchase from that salesperson to assuage the feeling of guilt.

3

Within the framework of interpersonal relations, there were two other articles attributable to marketing academics, one focused on research response rates and the other on teacher evaluations. Cialdini and Rhoads (2001) review a large quantity of past research which investigates the role of reciprocity in the process of social influence. The authors suggest that reciprocity is one of six psychological principles (also including scarcity, authority, consistency, liking, and consensus) that impacts persuasion, citing research on the granting of concessions to individuals in order to increase participation in research (e.g., reducing the expected survey duration to 20 minutes from an hour, etc.). Here again, we see how reciprocity might be implicated in altering people’s behavior. The last interpersonal marketing paper investigated the role of reciprocity in student evaluations of teacher effectiveness (Clayson 2004). The author found that past grades received did in fact impact future evaluations of teacher effectiveness, however given that the student’s were evaluating classes from 1-2 semesters before the research was conducted, it is not clear if the same relationship would hold if the typical student evaluations (given during the semester) were explored.

Reviewing the definitions of reciprocity (see table #1 on the following page) offered in the marketing research on interpersonal relationships suggests two important facts: (1) there is little consensus on the definition of what reciprocity is in marketing relationships; and (2) there is a lack of research investigating the role of negative reciprocity in marketing relationships.

These are the first of many gaps in the literature that need to be addressed.

4

Table #1. Reciprocity Definitions in Marketing Interpersonal Relationships

Moyer, 1970; Journal of Reciprocal purchasing - both the use of purchasing power to obtain

Finney, 1978

Houston and

Gassenheimer,

1987

Marketing

Journal of

Marketing sales and the practice of preferring one's customers in purchasing

Reciprocity - the process whereby a mutual exchange of acceptable terms is actualized; it is a social interaction in which the movement of one party evokes a compensating movement in some other party

Dawson, 1988

J. Health

Care MKT.

Frenzen and Davis,

1990

Miller and Kean,

1997

Dahl, Honea and

Manchanda, 2005

JCR

Psychology and

Marketing

JCP

Reciprocity - a cultural norm whereby individuals enter into an exchange with the anticipation of receiving personal benefits

Norm of reciprocity - use of a purchase occasion in the short term to repay outstanding social debts

Reciprocity - the degree to which individuals expect cooperative action

Interpersonal Reciprocity - emphasizing concern for others or strong attachment to others

Institutional Reciprocity - having a built-in system for calculating the costs versus the benefits involved in the exchange

Norm of reciprocity - an obligation for people to return in kind what they've received from others

Cialdini and

Rhoads, 2001

Clayson, 2004

Marketing

Research

MER

Reciprocity - an obligation for people to return in kind what they've received from others

Reciprocity - evidence that student written teacher evaluations are related to grades received

1.1.2 Reciprocity in Interorganizational Relationships

In the B2B relationship framework, Kumar, Scheer and Steenkamp (1998) investigated the existence of reciprocal punitive actions in auto-dealers’ relationships with their suppliers.

While these authors did not define reciprocity explicitly, the implied definition was evident in the existence of higher rates of punitive dealer actions as a response to higher levels of supplier punitive actions. Johnson and Sohi (2001) measured and found support for their conceptualization of reciprocity as returning good for good between relational partners. They developed a 6-item scale that captured the “positive reciprocity” as an outcome of interfirm connectedness. Palmer (2002) attempted to measure reciprocity as a predictor of effectiveness in cooperative marketing associations, however his measure failed to predict effectiveness.

Expanding on the lack of significance, Palmer suggests that his measures (being drawn from the power/dependence literature) failed to capture reciprocity. Lee et al. (2008) modeled

5

reciprocity as the outcome of mutualistic benevolence and altruistic benevolence in a framework that is questionable in relation to the existing understanding of relationship marketing. Troubled not only by the definition (see Table #2), this research is also challenged with an inadequate conceptualization. The measure of reciprocity was the combination of two questions: (1) Has your company helped this foreign exporter on at least one occasion; and (2)

Has this foreign exporter returned the favor on at least one occasion? While this measure quite possibly captures one instance of a reciprocal interaction, it does little to explicate the role of reciprocity in an ongoing relationship. Are we to assume that one beneficial act reciprocated by a partner implies a healthy social exchange over the duration of the relationship?

Frazier and

Colleagues, 1986,

1989 and 1991

Table #2 Reciprocity Definitions in Marketing B2B Relationships

Reciprocity - (implied definition) the actions taken by one party in

JM and JMR response to the actions taken by the other party in an exchange relationship

Kumar, Scheer and

Steenkamp, 1998

JMR

Reciprocity - (implied definition) evidenced by the existence of higher levels of dealer punitive actions in response to higher levels of suplier punitive actions

Johnson and Sohi,

2001

Palmer, 2002

Lee, Jeong, Lee and Sung, 2008

Pervan and

Johnson, 2003

IJRM

J. Strat.

Marketing

IMM

JCR

Reciprocity - partner response is contingent on actions; mutually contingent exchange of benefits; ensures long run gratification for partners

Reciprocity - a disposition to return good for good in proportion to what they receive; to resist evil, but to do no evil in return; and to make reparation for the harm we do

Reciprocity - mutual exchange of helping behaviors between importers and exporters

Reciprocity in RM is an expectation that good is returned for good in a fitting and proportional manner, resist negative acts but not return negative acts, and make reparation for any harm we do.

Pervan, Bove and

Johnson, 2009

IMM Same as above.

Some more recent work by Pervan and Johnson attempts to develop Gouldner’s conception of reciprocity. In their first paper (Pervan and Johnson 2003), the authors develop a marketing based definition of reciprocity from the literature and theory on reciprocity in social relationships (see Table #2). Their second paper (Pervan et al. 2009), attempts to conceptualize

6

and develop a scale to measure reciprocity in B2B relationships. In attempting to develop a scale to capture four proposed dimensions (make reparations, non-retaliation, returning good for good and resisting evil) they found a 2 dimension scale explained the responses the best.

These dimensions were called Exchanging good and Response to Harm. In reality most of the components of the exchanging good dimension appear to be based on equality of outcomes, which should be related to reciprocity, but definitely is not the same as reciprocity. Additionally, the response to harm dimension appears to capture more about cooperation between partners than it does reciprocal exchanges. Again, cooperation should be related to reciprocity; however reciprocity being a time delayed response to an action by a partner does not necessarily imply concurrent cooperation.

1.1.3 Reciprocity in the Relationship Marketing Literature

Relationship marketing (RM) entails a substantial stream of literature in the field of marketing. In a compelling article on the relationship development process, Dwyer, Schurr and

Oh (1987) describe five stages that social actors engage in: (1) awareness, (2) exploration, (3) expansion, (4) commitment, and (5) dissolution. Further, they explain that the exploration stage is sub-divided into 5 processes including (1) attraction, (2) communication and bargaining, (3) development and exercise of power, (4) norm development, and (5) expectation development.

While reciprocity is implicitly included in more stages than just the communication and bargaining phase of the exploration stage, these authors specifically discuss the role of reciprocity during this stage of the relationship. At that point in the relationship, both parties have some interest in furthering the relationship, they have mutually decided to exchange over some indeterminate period of time, and are in the process of exploring exactly how receptive their counterpart will be to a mutually beneficial relationship. It is expected that parties will try to reveal specific information about themselves, their needs, and or their resources. It is

7

suggested that if the relationship is to endure, “intimate disclosure (of information) must be reciprocated” (p. 16). Further it is suggested that later in the relationship, there may be a lesser need for strict-reciprocal accounting in that the future holds ample opportunity for, and expectations of, the balancing of outcomes over time.

Dwyer, Schurr and Oh (1987) also implicate reciprocity during the second phase of the relationship building process, the exploration stage. While they acknowledge that one party may have more power over (ability to mediate the rewards of) their partner, they detail that the unjust use of power (for the selfish gain of the more powerful partner) will lead to quick dissolution, whereas legitimate or just uses of power which benefit both parties can actually strengthen the relationship. Further, during the norm and expectation development stages, it is clear that norms and expectations which support mutual gains will develop a stronger relationship than those which are self-serving. These authors suggest that trust begins to develop during these stages, and is a critical component to relationship continuation. Trust leads to higher levels of risk taking which encourage the norm of reciprocity (granting concessions, proposing compromises, etc.).

The third relationship phase is the expansion phase. Here norms and behavioral expectations have led to a trusting relationship. During the expansion phase, trusting partners risk to expand the benefits provided to their partners (and themselves) which has the effect of increasing the interdependence of the actors on one another. Increased interdependence of both parties can lead to higher levels of trust, commitment and reduced conflict between the parties (Kumar et al. 1995a). Finally, the last stage of continuing relationships is proposed to be the commitment phase. Now existing relational norms, expectations of future behaviors, trust, higher levels of risk taking and increased interdependence create an expectation and a desire for both parties to maintain (or expand) the relationship as it provides beneficial outcomes to

8

both partners in both an absolute sense, and in a relative sense (Thibaut and Kelley 1961).

While Dwyer, Schurr and Oh only briefly mention reciprocity in their theory, it is clear that it is implied throughout the relationship development process. Each party makes investments exhibiting increasing levels of risk, over time, to communicate their role as an effective partner and build commitment and dependence from the other in a series of repeated interactions and exchanges. Clearly this is the development of reciprocity between two social actors.

Shortly thereafter, Morgan and Hunt (1994) developed and tested their Commitment-

Trust theory of marketing relationships, also referred to as the Key-Mediating Variable model

(KMV), due to the key roles of commitment and trust as mediators in marketing relationships.

One of the most highly cited articles in marketing (Cited by 4488 according to Google Scholar),

Morgan and Hunt built on Dwyer, Schurr and Oh by suggesting that all relational investments were mediated through commitment and trust which in turn impacted all relational outcomes.

Morgan and Hunt find support for the majority of their hypotheses. Some notable exceptions were that relationship benefits did not tend to lead directly to commitment and that opportunistic behavior exhibited a direct path to conflict (+) and uncertainty (+). They also note the possibility that additional mediators may exist that they have failed to capture. Additionally, their results suggest that firms acquiesce to their partner not necessarily for fear of power (prior assumption) but because they are committed to their partner. Numerous extensions of the

KMV model have consistently found support for the general framework; however some more recent work suggests that commitment and trust may not be the only mediators at play in marketing relationships.

In a meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of relationship marketing strategies,

Palmatier et al. (2006a) explore the Morgan and Hunt framework by compiling and analyzing empirical results from 94 different published and unpublished manuscripts. In broad terms their

9

framework was motivated by both Dwyer Schurr and Oh (1987) and Morgan and Hunt (1994) in that they tested a model of RM strategies → relational mediators → outcomes. The metaanalysis broadly finds support for the framework; however some interesting findings suggest that there may be some missing mediators in this framework. Examples include a finding that beyond the path through the relational mediators, dependence and relationship investments had a direct effect on seller performance. It is difficult to suggest that this direct effect is not mediated by some relational variable, as ceteris paribus financial investments in the relationship should not lead directly to positive outcomes for the investor. One plausible path these investments might take leading to outcomes for the investor is if their partner reciprocates the investment through increased purchase, spreading positive word of mouth, or reductions in opportunistic behavior. Similarly one would not expect that higher levels of dependence on a seller would necessarily lead directly to better performance for the seller. Much research has suggested that greater levels of asymmetric dependence (favoring a seller in this case) actually lead to higher levels of conflict and possibly relationship dissolution without some compensating mechanism to increase the dependence of the other partner (seller on the buyer). These findings lead the authors to suggest that “… the extant relational-mediated framework is not comprehensive and that additional mediators (e.g., reciprocity) must be investigated to explain the impact of RM on performance fully” (p. 150). Additional support for this extension is provided by Morgan and Hunt (1994) who find that opportunistic behavior displayed the largest effects on outcome variables (both direct and indirect). While Morgan and Hunt argue that it might be beneficial to allow for direct effects of opportunistic behavior, another interpretation is that opportunistic behavior is not only mediated through commitment and trust, but possibly another relational construct like reciprocity. Do relational partners punish when they feel their partner has appropriated too much of the benefits of the relationship?

10

Extending this work, Palmatier et al. (2009) find support for the role of gratitude and gratitude based reciprocal behavior as mediators in the relationship marketing framework.

While this finding does have implications for an overall role of reciprocity, it is important to note that they measure felt gratitude (described as short-lived) and resulting reciprocity based behaviors. This research is positioned within RM episodes or cycles whereby the seller can see the gratitude based response of the buyer over a series of individual exchanges. The authors find support for the role of gratitude based reciprocal actions as a mediator between RM investments and firm outcomes. Two important questions are brought up by the conceptualization in this research: (1) is gratitude a necessary component for reciprocal exchange; and (2) what might impact the gratitude based reciprocal response within a relationship?

1.2 Primary Motivating Research Questions

An additional concern that is raised by extant marketing research is that the response to negative or detrimental actions is not often considered in this research. It is unclear whether the appropriate response would be some sort of punishment or retaliation, or whether marketers should always “turn the other cheek” when faced with a detrimental situation. What about the evidence for the role of negative reciprocity? Are we to assume that in all marketing relationships, the best (only?) response to a partner’s self interested behavior is exit from the relationship? Doesn’t reciprocity include the response to harmful actions as well as to beneficial actions?

Figure #1 charts the domain of reciprocity research in marketing. The common assumption in marketing (either explicitly, or implicitly) is that relationships are either cooperatively built, based on positive reciprocity (Pervan et al. 2009), or that they will end up dissolving. There are exceptions to this general trend; Kumar, Scheer and Steenkamp (1998)

11

investigate the reciprocation of punitive actions in supplier-dealer relationships. Frazier and

Rody (1991), and Frazier and Summers (1986) find evidence of reciprocity by significant correlations between supplier and dealer actions (both coercive and non-coercive strategies), however Frazier, Gill and Kale (1989) find no evidence of reciprocal coercive actions from dealers who have very few alternative suppliers. Interestingly, these findings might provide some preliminary support for the idea that negative reciprocity (or returning a punitive act in response to one) will result in the degradation of marketing relationships. We see that higher levels of supplier punitive or coercive actions lead to similar responses from dealers. It appears from these studies that responding to an “evil” with an “evil” may lead to a spiral of increased retaliation and revenge. But does this finding always hold? What boundary conditions might make retaliation less likely when one party commits a “punitive act”?

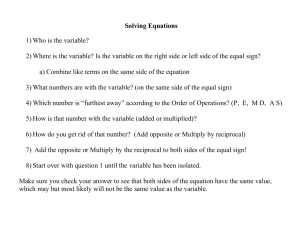

Figure #1. The Domain of Marketing

Interactions

"Recipient" Response

Positive Negative

Positive

Most

Marketing

Research

Perceived

"Donor"

Action

Negative

Kumar et al. '98,

Frazier et al. *

Shaded Region - Reciprocity according to Becker

* 1986, 1989, 1991

We all know from experience that any relationship has challenges and problems. Figure

#1 shows that the marketing reciprocity research has only studied reciprocity in a very small

12

area of the possible interactions between exchange partners. The interesting interactions have been left to behavioral economists in sterile laboratory settings. What happens when one partner suspects he is being taken advantage of? Does a negative response to an unjustified negative action have beneficial outcomes for the relationship or does it lead to the degeneration of the social interaction? When is it viable to strategically avoid responding to a partner’s actions? There are numerous questions which need to be addressed with respect to the role of reciprocity in marketing relationships.

While there are numerous directions that would help build a better understanding of reciprocity in marketing relationships, this dissertation focuses on two distinct research perspectives. The first investigates the role of episodic reciprocity between relational partners.

This perspective approaches reciprocity as part of a single interaction between actors in a marketing interaction. The specific research questions addressed are:

1) Is reciprocal debt created in marketing relationships?

2) What characteristics of an exchange will impact the reciprocal response to a given action?

3) How do business partners respond to detrimental partner-actions, and what factors will mitigate any potential retaliation?

The second perspective positions reciprocity as an ongoing relational process. This approach proposes that reciprocal behavior in ongoing relationships is a multi-dimensional process that can enhance relational outcomes. While it is important to investigate a response to a given action, relationships happen over time and over the course of numerous interactions.

This research investigates the role of reciprocation over time within ongoing relationships and asks some very important questions:

1) What is the role of reciprocity in the development of ongoing marketing relationships?

2) Which characteristics of a relationship and the business transactions impact reciprocity over time?

13

1.3 Organization of the Dissertation

The remainder of this dissertation is organized into six chapters. The next chapter provides a literature review of reciprocity theory and research from other disciplines. Chapter three develops a general theory of episodic reciprocity. Chapter four describes the survey and experimental research completed to investigate episodic reciprocity. Chapter five develops a general theory of ongoing or relational reciprocity in marketing relationships, and provides results from a survey designed to test the research hypotheses. Finally, chapter six discusses the conclusions and implications of the dissertation research. References and appendices including survey materials and cover letters are attached at the end of the document.

14

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

“… we ought to be disposed, as a matter of moral character, to make reciprocity a moral obligation.”

- Lawrence C. Becker

If 20 people were asked to define reciprocity, like a lot of abstract constructs, there would be some general agreement between the definitions; however none of them would adequately define the entire conceptual domain of the term. This problem is highlighted when the academic literature on reciprocity is reviewed. Not only is there a lack of consensus of a definition of reciprocity, but there is very little agreement on the way reciprocity is conceptualized as well. Reciprocity has been a cultural phenomenon throughout recorded history in nearly every society, as can be seen in ancient writings from a number of cultures, for example:

“Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself”

- Analects of Confucius (circa 500 B.C., as cited in Wikipedia 2009)

Also, the Golden Rule – Do unto others as you would have done unto you - was adapted from the Bible verse: “Thou shalt not avenge, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself…(Leviticus 19:18)”. In fact nearly every religion espouses some version of this edict. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and Taoism all promote some derivative of the Golden Rule. While the Golden Rule itself is not the same as reciprocity, the fundamental concept, that we can expect behavior similar to our own from those we interact with, definitely relates to a general understanding of reciprocal behavior.

One of the most highly cited articles on reciprocity is Gouldner’s (1960) “The Norm of

Reciprocity”. Gouldner distinguishes between three distinct conceptual domains of reciprocity,

(1) reciprocal behavior, (2) existential folk beliefs in reciprocity, and (3) a moral norm of reciprocity. Gouldner argues that the moral norm of reciprocity is defined by two important

15

edicts: (a) people should help those who have helped them; and (b) people should not injure those who have helped them. His argument is based on the principal that reciprocity promotes stable and enduring relationships. The fact that a recipient of help should in turn help those who contributed in the first place ensures some enduring debt that people rely on in the future of the relationship. Further, the idea that the indebted partner should not harm the debtor, at least until the debt is repaid, helps to create peace and order within society. This brings up an interesting question, what role does punishment or retaliation (negative reciprocity) have in reciprocal relationships? Gouldner argues that since social debts are never paid entirely in full, there is always a reciprocal debt remaining and thus harm of the partner should be constrained.

While there is value in this position, we all know that in reality people do take revenge and often to those closest to them (e.g., “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned”).

In 1956, Howard Becker collected his introduction to sociology lectures from the

University of Wisconsin and printed them in a book titled “Man in Reciprocity” (Becker 1956). In this lecture series, Becker relates the development of all human social structures to reciprocity.

Coining the term Homo Reciprocus , Becker relates the mores of ancient civilizations, the development of the division of labor, teaching a child to be obedient, and everything in between to reciprocity between social actors and or social institutions. Becker argues that all social interactions can be interpreted based on the concept of reciprocity, although he intentionally fails to offer a definition of reciprocity, leaving it to the reader to formulate their own. Becker viewed reciprocity as responsible for teaching children socially acceptable behavior through parental responses to both proper and improper actions. Warm smiles or a slap on the wrist were responses to behavior that condition the child to repeat actions which were rewarded, and avoid actions that resulted in punishment. Thus Becker acknowledges that reciprocation to

“negative” actions can help reinforce socially acceptable behavior.

16

Another Becker, this one a philosopher with a first name of Lawrence (LB) disagrees with Howard Becker, not on the prominence of reciprocity in social relationships, but rather on the role of negative reciprocity in social relationships. LB’s book Reciprocity (1986) argues that reciprocity is a moral norm. To gain a solid understanding of this philosophical definition of reciprocity, I want to reprint the maxims from LB’s thesis which illustrate this normative position, and the disagreement with the sociologist:

1.

Good received should be returned with good.

2.

Evil received should not be returned with evil.

3.

Evil received should be resisted.

4.

Evil done should be made good.

5.

Returns and restitution should be made by the ones who have received the good or done the evil, respectively.

6.

Returns and restitution should be fitting and proportional.

7.

Returns should be made for the good received – not merely for good accepted or requested.

8.

Reciprocation, as defined by 1-7, should be made a moral obligation.

LB’s position is argued based on the idea that anything that promotes good (rather than evil) is a moral norm of which social actors should abide. LB argues that if evil is returned for evil received, the result is an escalation of revenge and punishment leading to the eventual degeneration of society as a whole. We can see in maxim #5 that LB proposes an alternative reaction to “evil received” in that the evil-doer should make up for the evil deed by providing

“fitting and proportional” restitution to the injured party. Would that it was so, our entire legal system might be out of work. Importantly to our building discussion on the definition of reciprocity, we see that this normative definition suggests that negative reciprocity should not be a part of healthy social relationships. How do we reconcile these different perspectives?

Perceptions of the recipient of a punishment must be an important consideration in considering “evil” actions. If LB’s maxims were completely correct, society would have degenerated by now. Instead, parents continue to punish children (even if not by spanking), marital partners punish through withholding affection or attention, business partners can

17

spread negative word of mouth, and if the perception is that the punishment is justified for prior actions, we expect to see these relationships persist. LB hints at the value of recipient perceptions in maxim #6 by stating that returns and restitution should be “fitting and proportional”. While this is not a statement about negative reciprocity, it is a hint that perceptions about the appropriateness of reciprocal reaction are important.

Gouldner supports this view that recipient perceptions are important in the valuation of reciprocal responses to positive actions. He describes the valuation process of the help (and hence the debt) received, and argues that it is affected by:

1.

The intensity of the recipient’s need at the time the benefit is bestowed

2.

The resources of the donor

3.

The motives imputed to the donor by the recipient

4.

Nature of constraints perceived to exist (costs to the donor)

Later empirical work has offered support for much of Gouldner’s theory. Motives were found to reduce reciprocal responses when they were perceived as inappropriate (Lerner and Lichtman

1968; Schopler and Thompson 1968). Additionally, subjects who were intentionally underrewarded tended to reciprocate less, and evaluated their exchange partners more poorly, than subjects who were under-rewarded “by chance” (Leventhal et al. 1969). Importantly, this suggests that reciprocal responses to actions will vary depending on the recipient’s perceptions.

Another perspective on reciprocity is that some people exhibit a resistance to take on a reciprocal debt. Brehm and Cole (1966) termed this concept psychological reactance which is defined as the resistance to a felt loss of freedom, resulting in hostility and acting out.

Berkowitz (1973) found that reactance is increased when a request for help is perceived as

“improper”. A vast amount of literature in psychology focuses on the impact of recipient perceptions on reciprocal (positive and negative) responses and ratings of the donor.

To review, there is much agreement that reciprocity includes the return of some benefits for benefits received. There is disagreement about the role of negative reciprocity, or

18

retaliation. Some theorists suggest that returning evil for evil received should be avoided

(Becker 1986; Gouldner 1960), others suggest that punishing can actually be beneficial to the development of acceptable social norms (Becker 1956; Michaels 1983). There is much agreement that reciprocal responses involve perceptual valuation of the action (positive or negative) received (Bolton et al. 1998; Eisenberger et al. 1987), and the motives at play by the donor (Leventhal et al. 1969; Michaels 1983; Rabin 1993). There are definite implications that reciprocity occurs over time, and many authors suggest that the waiting time until reciprocal debts are repaid actually supports a positive social interaction as both parties have an interest in not harming the other at least until the debt has been repaid. Evidence also suggests that reciprocal responses can vary depending on the situation, and that some people (or situations) will exhibit a resistance to accepting a reciprocal debt. However, very few articles offer any explicit definition of the term, and the few that do only capture some subset of the concepts discussed to this point (see Table #3 below).

19

20

CHAPTER 3: A GENERAL THEORY OF EPISODIC RECIPROCITY IN

MARKETING RELATIONSHIPS

3.1 Episodic Reciprocity Abstract

Relationship marketing research relies on the implicit inclusion of reciprocation. One relational member (typically the seller) performs some action that is intended to elicit a response from their customer. The assumption is that investments in relationship marketing programs will be reciprocated back to the seller through increased purchases, increased loyalty, or improved relationship quality. In reviewing the extant marketing literature, it is obvious that reciprocity is neither clearly defined, nor accurately measured within marketing relationships.

Furthermore, the role of reciprocity in the process of relational exchange has been overlooked in the marketing literature. This research will address these issues. Building on social exchange, reciprocity and relationship marketing theories, a process model of reciprocal exchange is proposed. Factors which should influence reciprocal responses to both beneficial, and harmful, actions are proposed. The role of the norm of reciprocity, and its influence on reciprocal responses will be tested. Further, both positive and negative reciprocal debts are conceptualized and measured as outcome variables in marketing relationships. This research will be empirically tested through both a survey in a B2B setting, and a lab based experiment to test the proposed process model of episodic reciprocal exchange.

3.2 Episodic Reciprocity Introduction

In proposing the Commitment-Trust theory of relationship marketing (RM), Morgan and

Hunt (1994) developed a framework that described how relational characteristics between partners lead to trust and commitment, and how these key relational mediators impact dyadic outcomes. This approach focused less on specific behaviors and more on the overall dynamics

21

that define the marketing relationship. These are more enduring characteristics of the relationship including the dependence structure, shared values, communication and opportunistic behavior measured at a global relationship level. While it is clear that commitment and trust are highly correlated with beneficial relational outcomes, the commitment-trust theory did little to suggest specific actions business partners could utilize to improve the relationship outcomes.

More recently, RM researchers have approached relationship marketing as a strategy enacted by relational partners to build and strengthen long term business relationships (Bagozzi

1995; Cannon and Perreault Jr 1999; Gronroos 1999; Jap et al. 1999; Palmatier 2008; Palmatier et al. 2007a). These researchers attempt to categorize investments in RM and to quantify differential impacts of RM investments on financial outcomes (usually for the “selling” firm) of the dyad. RM categories have been defined as financial, structural and social (Berry 1995;

Palmatier et al. 2008; Palmatier et al. 2007a), and research investigating the financial impact of these different categories of RM suggest that they have unique effects on financial outcomes

(Palmatier et al. 2006b). For instance, social RM efforts had the largest direct effect on customer specific returns (a proxy for the contribution margin a rep firm earns from a specific customer), structural RM investments had the largest impact for firms that had frequent interactions, and financial RM investments did not exhibit any direct effects on customer specific returns.

While both perspectives are valuable for understanding business relationships, both the

Commitment Trust and the Relationship Marketing approaches fail to capture the process which transforms one member’s actions (investments, behavior, etc.) into financial outcomes for either themselves, or their partner. RM assumes that financial, social or structural investments will result in financial benefits not only for the investor, but also for their partner. This research

22

argues that it is important to understand the process which translates these investments into objective performance outcomes for either partner. Even if trust and commitment are directly impacted by RM investments, what process extracts financial returns from trust and commitment? In order for any business to increase their outcomes based on relationship investments, their partner must in some way repay that effort. RM research implicitly relies on reciprocal exchange of investment and return from marketing relationships (e.g., Doney and

Cannon 1997; Li and Dant 1997; Morgan and Hunt 1994); however that process is rarely defined nor explicitly measured in the extant literature. In fact, authors of a recent meta-analysis suggest that “integrating reciprocity into the relational-mediating framework may also explain the large, direct effect of relationship investment on performance, such that people’s inherent desire to repay “debts” generated by sellers’ investments may lead to performance-enhancing behaviors, independent of trust or commitment” (Palmatier et al. 2006a, pg. 152).

This research posits that the process of reciprocity is a critical component to marketing exchange. While reciprocity is mentioned often in the marketing literature, the failure to accurately conceptualize, define or measure the role of reciprocation has resulted in a lack of understanding of the process of reciprocation in the development of marketing relationships.

Building off of reciprocity, relationship marketing and social exchange theories, this research will investigate the role of reciprocal behavior, norms of reciprocity, and relational characteristics proposed to affect reciprocal exchange.

3.3 Episodic Reciprocity Conceptual Development

Relationships do not happen at one point in time; they are dynamic, evolving and occurring over time. Reciprocal exchange occurs over several interactions within a given relationship (Bagozzi 1995; Macneil 1980). Given this understanding, it would be appropriate to consider all actions within a relationship as reciprocal actions. In fact Gouldner (1960) suggests

23

that the norm of reciprocity encourages the first trusting act by one party to a potential relationship by reducing the risk that their efforts will be taken advantage of; every action after this first effort is considered a reciprocal response to prior actions.

What types of actions are being referred to? Given that relationships are dynamic and occurring over time, expectations are developed for future interactions based on prior exchange occasions. The status quo becomes the expected range of actions over time as the relationship develops and partners become more familiar and comfortable with each other in the exchange process (Bagozzi 1975; Dwyer et al. 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Actions can easily be categorized any number of ways. This research distinguishes between beneficial actions and detrimental actions. Beneficial actions are defined as any action which is perceived to have a more positive effect than expected given the status quo of the relationship (e.g., an unexpected price discount offered to a customer, supplier investments in an integrated distribution system that increases customer profitability, etc.). Similarly, a detrimental action is defined as any action which is perceived to have a more negative effect than expected given the status quo of the relationship (e.g., unexpected reductions in product quality due to cost increases, reduction in sales force which causes service quality deterioration, etc.). Obviously these actions do not cover the normal interactions involved with making repeated purchases, paying accounts receivable, or making a regular periodic sales call on a customer.

Relationship marketing research has focused on the beneficial actions as investments

(of financial or non-financial resources) that a seller makes to build a stronger relationship with its customers (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Bowman and Narayandas 2004; Palmatier et al.

2006b). Other research has examined how detrimental actions can affect relational outcomes

(Frazier and Rody 1991; Hibbard et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 1998). While much of this research suggests that beneficial actions lead to more positive exchange outcomes, and detrimental

24

actions lead to more negative outcomes, the extant marketing literature fails to capture the process which enables specific actions to affect firm outcomes, or what relationship specific characteristics might impact the response to beneficial or detrimental actions by one’s business partner.

Business relationships involve prior social history, and expectations of future exchange

(Jap et al. 1999; Weitz and Jap 1995), however much (if not all) of the empirical work dedicated to measuring the role of reciprocity in social exchange has examined interactions between strangers with no social history, and no expectation of future interactions. The primary context for the existing reciprocity research is a sterile lab environment, where researchers often intentionally eliminate any chance of prior social interactions. Research set in the context of existing social relationships would provide a fertile ground to test theory about the role of reciprocity in social interactions. Building off social exchange theory, and incorporating empirical results from reciprocal dyadic exchanges (Fehr and Gachter 2000; Fehr and Gachter

1998; Loch and Wu 2008) into the theoretical RM framework of social relationships, this research will investigate factors which impact reciprocal responses to a partner’s action within the framework of established marketing relationships.

Substantial empirical evidence exists for various factors which affect reciprocal exchange, however very little investigates reciprocity within a social relationship . That is, most empirical research involves interactions between total strangers. Acknowledging that a social history may impact reciprocal behavior, Loch and Wu (2008) used a manipulation in a lab setting to simulate a social history. In the social condition, they allowed participants a brief introduction to get acquainted and then asked each participant to read the following paragraph:

“ You have already met the person with whom you will play the game. Now the person is no longer a stranger to you. You can imagine that the other player is a good friend. You have a good relationship and like each other ” (p. 1837).

25

In the control condition, players interacted anonymously, separated throughout the study. In a sequential move game, even with this weak manipulation, they find higher levels of trust and positive reciprocation in the social history condition than the control condition. On the other hand, Fehr and Gachter (2000) find that (lab manipulated) “partners” actually punish more severely for norm violations than do strangers, and Chen, Chen and Portnoy (2009) find that friends (existing student friendships) respond less positively to unfavorable, inequitable offers than do complete strangers. All of these examples illustrate that a history of social interactions

(even if those interactions are imagined) will impact future reciprocation between “partners”.

Does this suggest that the existence of a social relationship simply magnifies the level of reciprocal reactions to partner efforts? Without understanding perceptions of the actions, and the underlying relationship dynamics, it is difficult to determine with certainty how these findings will apply to marketing relationships.

Additionally, we know very little about the existence or role of negative reciprocity in marketing relationships. The relationship marketing literature advocates the philosophical, normative positive role of reciprocity, suggesting that evil not be responded to with evil (Bagozzi

1995; Pervan et al. 2009), but without testing responses to negative actions within functional relationships it is difficult to assume that avoiding punishment always provides the best solution. In fact, some analytical work from the behavioral economics literature suggests that

“unconditional cooperation” can result in overall deterioration of relational networks as those parties who tend to reciprocate positively will eventually tire of being taken advantage of (Sethi and Somanathan 2003). These inconsistencies suggest that the true range and role of reciprocal responses in marketing relationships is not fully understood. Does negative reciprocity impact marketing relationships? How will partners react to detrimental actions by their counterpart?

What relational dynamics will affect these reciprocal responses? The majority of evidence for

26

influences on reciprocal responses lies within the field of economics, where unfortunately social histories and expectations of future interactions have been designed away (Eisenberger et al.

1987; Falk et al. 1999).

3.3.1 Reciprocal Action – Debt Response Cycles

Reciprocity has been defined a variety of different ways in the marketing literature.

Numerous authors have defined reciprocity in line with Becker’s (1986) conceptualization of returning good for good received, and not harming a relational counterpart, even if you have been harmed by them (Bagozzi 1995; Palmer 2002; Pervan et al. 2009; Pervan and Johnson

2003). Others have defined reciprocity either explicitly or implicitly (through their measurements) as the existence of similar tactics used by members of a marketing relationship

(Clayson 2004; Kumar et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2008). Interestingly, in a stream of research by

Frazier and colleagues (Frazier et al. 1989; Frazier and Rody 1991; Frazier and Summers 1986), the authors define reciprocity as actions taken by one party in response to the actions taken by the other party in an exchange relationship, however their empirical evidence for the existence of reciprocity is a correlation between buyers and sellers’ use of coercive tactics. While they define reciprocity as being any action which is induced by the action of a partner, they measure it by only “in-kind” returns of potentially destructive behavior.

This research will adopt the definition of reciprocity offered by Frazier and colleagues as: actions taken by one party in response to the actions taken by their counterpart in an exchange relationship. This definition of reciprocal behavior is also supported by Houston and

Gassenheimer (1987), who define reciprocity as “a social interaction in which the movement of one party evokes a compensating movement in some other party” (pg 11). Importantly this definition of reciprocal behavior does not require that the response to any action is necessarily an action “in-kind.” Note that is also does not imply that reciprocation necessarily takes place

27

immediately. In fact, the time lapse between the acceptance and repayment of a reciprocal debt may be an important component of reciprocity (Becker 1956; Becker 1986).

Reciprocity theory argues that actions by one member of a relationship create in their counterpart a reciprocal debt that must be repaid in the future in order for the relationship to endure (Cialdini and Rhoads 2001; Gouldner 1960; Macneil 1980). When this reciprocal debt involves the repayment of some beneficial action, it is suggested that the existence of a debt can actually help to build social solidarity, or the degree of integration in society. This is so because during the elapsed time between the incurrence and the repayment of the debt, it is expected that both parties will avoid harming the other (Macneil 1980). Gouldner (1960) claims that during this time period, when debts have yet to be repaid, the person owing the debt is “morally constrained to manifest their gratitude toward, or at least to maintain peace with, their benefactors” (pg 174). When the reciprocal debt involves the return of a benefit or favor, it is contrary to the self interest of both parties to harm the other: the debtor avoids harming the creditor for fear of reduced chances of gaining a benefit in future interactions; and the creditor because it may reduce the chances of the existing debt being fulfilled. It is exactly this process which Macneil (1986) argues enables reciprocity to satisfy the dual, conflicting interest of

“schizophrenic” man: self interest and social solidarity. Cialdini (2009) claims that the social debt, or future obligation, created by the rule of reciprocity is directly responsible for the unique social advantages of the human race.

Evidence suggests that these social debts are actually consciously recognized by relational partners, and have predictive power over behavior in future exchange (Frenzen and

Davis 1990). Frenzen and Davis (1990) find that individuals who claim to owe a social debt to a sales host are more likely to purchase in a home selling context than are those who claim no existing debt. In this study, the debts referred to were prior home selling events during which

28

the current host either purchased from the individual (causing a social debt needing to be repaid in the future), or did not purchase (and hence created no reciprocal debt). Further evidence for the existence of reciprocal debts is shown through an experimental selling context, during which customers actually reported feeling guilty if they did not make a purchase from a salesperson when social connectedness exists, and often returned to make a future purchase from that salesperson to satisfy their reciprocal debt (Dahl et al. 2005). This feeling of guilt was also found in a consumer relationship management context (Palmatier et al. 2009) when consumers were unable to repay reciprocal debts. Eisenberger, Cotterell and Marvel (1987) find that recipients of help or favors experience a feeling of obligation and indebtedness. Cialdini (2009) argues that any benefits received from a relationship create debts which require reciprocation to be fulfilled.

Based on reciprocity theory, positive reciprocal debt is defined as: the conscious recognition that a benefit is owed to a relational partner in repayment of a benefit received. It is important to note that there are response options available to someone after they receive some beneficial treatment from there partner that would fulfill the reciprocal debt that is created. The assumption of course is that in a given relationship, if person A does something that benefits person B, then at some point in the future B will do something to benefit A. This would be a mirrored response strategy. Alternatively, it is possible that A could eliminate B’s debt through some counter-valenced compensatory action. For example maybe A takes more than their fair share in a future interaction with B. Extant research has focused on the mirrored response strategies, but a counter-valenced strategy is also a possibility. These possible responses are illustrated below in figure #2:

29

Figure #2 Positive Reciprocal Debt Responses

A’s Action

Benefits B

B’s Positive

Reciprocal Debt

B’s Action

Benefits A or

A’s Action

Benefits A

While it is acknowledged that reciprocity can work both upstream and downstream in a marketing relationship, consistent with the relationship marketing literature this research will focus on a selling firm’s actions and their customer’s response. Based on the prior discussion, the following hypothesis is offered:

H1: Beneficial actions by a selling firm will lead to a positive reciprocal debt felt by their customer.

So what are the expected outcomes to these positive reciprocal debts? Theorists agree that the existence of positive reciprocal debts helps to ensure the health of the relationship

(Becker 1986; Gouldner 1960; Macneil 1980). Positive reciprocal debts serve at least two beneficial purposes in a relationship, the first is that at some point the debt will be repaid, helping enforce the norm of reciprocity and a healthy exchange relationship (Macneil 1986;

Macneil 1980). Additionally, it is argued that the existence of positive reciprocal debts create a barrier to harmful actions in that both parties are motivated to maintain the peace, at least until the debt has been repaid (Gouldner 1960). It has also been suggested that in most relationships, the balance of existing reciprocal debts is never exactly paid so that there always remains a reciprocal debt to help ensure the health of the relationship (Becker 1986).

Relationship marketing theory relies on customer reciprocation of seller relationship investments (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Selling firms invest in financial, social or structural relationship marketing programs relying on the idea that their customer will reciprocate those

30

efforts through increased loyalty, order frequency and quantity, and possibly through positive word of mouth (Palmatier et al. 2006a). While the role of reciprocal debts has not been explicitly investigated in marketing research, evidence suggests that relationship marketing investments do provide returns to selling firms through increased sales, share of wallet, and reduced customer switching behavior. If seller initiated beneficial actions do translate into improved seller performance, the existence and subsequent satisfaction of reciprocal debts must explain some of the gains for selling firms. Therefore, I expect that:

H2: Customer positive reciprocal debt will lead to increased selling firm outcomes.

But what should be expected of detrimental actions? We have established that reciprocity does not only refer to the return of benefits gained for benefits received. Based on the definition of reciprocal behavior as actions in response to those of a relational partner, we must also consider how a customer will respond to detrimental actions in a relationship. Becker

(1986) argues that evil actions should not be responded to with evil, however empirical evidence suggests otherwise. Numerous marketing researchers have found that potentially harmful actions by one partner are often correlated with similar harmful actions by their counterpart, and interestingly, these relationships have survived despite the apparent negative reciprocation. Kumar, Scheer and Steenkamp (1998) find that the use of punitive capabilities by a channel member is positively correlated with similar use by its channel partner. Similarly,

Frazier and colleagues (Frazier and Summers 1984; Frazier and Summers 1986) find that dealers and manufacturers’ use of coercive tactics are highly correlated. In an interpersonal setting,

Clayson (2004) finds that students who received grades lower than they expected in class tended to evaluate their professors more severely than those whose expectations were met, suggesting a type of punishment for the perceived mistreatment.

31

Experimental evidence also suggests that people will punish for perceived detrimental actions. For example, Greenglass (1969) found that participants whose task performance was hindered were likely to exert effort to hinder “similar-others” in the future. In another experiment, when the experimenter divulged that participants were to be intentionally underpaid for their participation, these individuals punished the experimenter by underperforming compared to those who were “unintentionally” underpaid (Michaels 1983).

Evidence suggests that this tendency to punish for detrimental actions persists even when the absolute outcomes favor the individual, for example Keysar, Converse, Jiunwen and Epley

(2008) find that when the same outcomes are framed as a partner taking some of their counterpart’s endowment, those counterparts tend to punish in future interactions, however if the exchange is framed as the partner giving some of their own endowment, future exchange shows evidence of positive reciprocity. This suggests that in response to a perceived detrimental action, and given the opportunity to do so, people may retaliate or punish their partner. While it is possible that this response happens immediately, it should not always be the case. The opportunity when a fitting and proportional punishment is available may take time to develop.

Negative reciprocal debt is therefore defined as: the intent to respond to a detrimental action through either (a) punishing the responsible party, or (b) by acquiring extra benefits from the responsible party at some point in the future. It should be noted that the two options offered above provide two distinct routes to the satisfaction of the reciprocal debt. The first is a mirrored response strategy whereby the harmed party punishes their partner in the future.

Alternatively, they would expect their partner to make up for the detrimental treatment by providing some compensation to them in the future. In both cases, the focal partner has been slighted and expects something to occur to make up for the mistreatment. However it is

32

acknowledged that the route to the satisfaction of that reciprocal debt may depend on characteristics of the person, and of the situation. These response strategies are illustrated below in Figure #3: