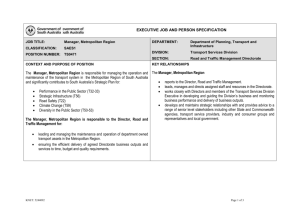

Course Project World Wide Tracers, Inc. v. Metropolitan

Course Project

World Wide Tracers, Inc. v. Metropolitan Protection, Inc., 1986 Supreme Court of Minnesota

Summary

World Wide Tracers, Inc. (World Wide) sold assets and properties, including equipment, furniture, uniforms, accounts receivable, and contracts to Metropolitan Protection, Inc.

(Metropolitan) in form of a security agreement and financing statement in favor of World Wide.

Metropolitan then executed a security agreement and financing statement in favor of State Bank.

Two years after the initial agreement was executed with World Wide Metropolitan defaulted.

World Wide brought suit, asserting its alleged security agreement in Metropolitan’s accounts receivable. State Bank filed a counterclaim asserting its perfected security interest in

Metropolitan’s accounts receivable. (Cheeseman, Business Law, 2010, Case 27.2) i

Summary Judgment

In 1986 World Wide unsuccessfully asserts in the Supreme Court of Minnesota its alleged security agreement in Metropolitan’s accounts receivable. World Wide’s appeal is denied. The agreement between World Wide and Metropolitan states “all of the property listed on Exhibit A (equipment, furniture, and fixtures) together with any property of the debtor acquired after” is to be used as collateral. The court finds insufficient clarity, ambiguity, in the definition of the word property as to be pertaining solely to tangible, and not intangible. The burden of perfection lies on World Wide as they drafted the security. The judge references

Cherne v. G&A, Inc., Minnesota 1979. “Also, if the appellant had intended to encumber more than just tangible property, it could have so stated by using the description ‘any property, tangible or intangible.’ Where there is an ambiguity in a contract, the contract will be construed against the drafter.” (Cherne Industrial, Inc. v. Grounds & Associates, Inc., Minnesota, 1979) ii

Parties

World Wide is the petitioner, appellant, and plaintiff in this case. World Wide on July 15,

1980 sells assets, properties, including equipment, furniture, uniforms, accounts receivable, and contract rights to the defendant, Metropolitan, formerly Protection Technologies, Inc. State Bank is respondent in this case rightfully claiming ownership of Metropolitan’s accounts receivables.

Facts

1.

On July 15, 1980 World Wide sold equipment, furniture, uniforms, accounts receivable, and contract rights to Metropolitan.

2.

The financing statement was filed on July 16, 1980.

3.

Exhibit “A” was attached to the financing statement filed on July 16, 1980.

4.

Exhibit “A” is a list of equipment, furniture, and fixtures owned by appellant and sold to debtor. Exhibit “A” does not include accounts receivables or contract rights

5.

In February 1982 State Bank executes two security agreements with Metropolitan.

6.

Language contained on the second financing statement describes collateral: “All accounts receivable and contract rights owned or hereafter acquired.”

7.

The financing statement was filed on March 3, 1982.

8.

Metropolitan defaulted in fall 1982.

9.

In April 1983 the trial court granted a default judgment in favor of World Wide.

10.

In May 1983 Metropolitan filed a motion to vacate the default judgment. World Wide makes a motion to recover Metropolitan’s accounts receivables

11.

In June 20, 1983 Metropolitan’s accounts receivables is presented as a separate matter aside from the default judgment in the court of appeals. World Wide’s motion to vacate the appeal is denied and World Wide appeals.

Procedure

In the initial court proceedings World Wide is granted default judgment over

Metropolitan’s property. Metropolitan and State Bank make a motion to vacate the default judgment. Metropolitan and State Bank are not seeking summary judgment in regards to tangible property. Metropolitan and State Bank make a motion to vacate because World Wide makes a motion to recover Metropolitan’s accounts receivables. The defendants and respondents believe

World Wide does not have rights of repossession or recovery on Metropolitan’s accounts receivables. This matter is permitted to be heard by the Court of Appeals. World Wide makes a motion to vacate which is denied. Ultimately World Wide is required to appeal.

In search for summary judgment the Court of Appeals ruling is appealed and sent to the

Supreme Court of Minnesota. The Court of Appeals provides ruling on September 10, 1985.

Judgment was provided in favor of State Bank because insufficient matter of law was produced to perfect World Wide’s claim to accounts receivables by Judge David Marsden; however, this matter is motioned toward the Supreme Court because Judge Popovich dissents.

World Wide’s appeal is filed on November 1, 1985 decided on November 1 by Judge

Amdahl to be heard in Supreme Court. On April 4, 1986 summary judgment is provided by

Judge Amdahl in the Supreme Court of Minnesota on the matter of World Wide v. Metropolitan.

Issues

There are two issues in this case. One is the strictness in which Uniform Commercial

Code (UCC) requirements on collateral descriptions should be applied in security agreements and financing statements. Two, is the description provided by World Wide’s financing statement sufficient to demonstrate interest in Metropolitan’s accounts receivable? The Supreme Court’s concerns include UCC requirements where in the Court of Appeals the issue is, “did the trial

court err in granting partial summary judgment in favor of Metropolitan State Bank, which awarded the bank accounts receivable to Metropolitan Protection?” (World Wide v.

Metropolitan, 1985) iii

Holdings

Article 9 of chapter 336 “requires the agreement to contain a description of the collateral with respect to a financing statement.” (Minnesota Statues Article 9 Chapter 336.9-203) iv

As the majority of courts interpret this statute liberally, “the code is meant to be comprehensive and flexible, and to free the law from artificial distinctions restricting the rational conduct of commercial financing.” (Pennsylvania Superior at 489, 433, A2d at 1360) v

It is possible that by definition one properly used descriptive word may sufficiently perfect a security. In this case the most descriptive usage was supplementation. Exhibit “A” is provided as explanation to what is meant by property in the financing statement. The types of property which are listed in exhibit “A” are all tangible. The UCC permits that indicating the

“type” of collateral secured rather than describing each item individually is sufficient. (World

Wide v. Metropolitan, 1986) vi

“The provisions of Article 9 and the official comments thereto support the conclusion that the security agreement embodies the actual agreement between the debtor and the secured party, and the financing statement need only provide inquiry notice to prospective creditors.” (World Wide v. Metropolitan, 1986) Effectively, World Wide’s security agreement must provide sufficient notice to anyone reading the document, and in this case, State

Bank that accounts receivables are covered in the corresponding financing statement.

In resolution of the second issue, determination if World Wide’s financing statement sufficiently demonstrates interest in Metropolitan’s accounts receivable, application of blanket liens are legal. In this case the financing statement lacks clarity, and can be misinterpreted. It

should not be misconstrued as a blanket lien. It is reaffirmed that State Bank is the rightful owner of Metropolitan’s accounts receivables because it is not clear that World Wide’s intentions were to secure accounts receivables in the security agreement.

Reasoning

World Wide drafted the security agreement. By law World Wide is required to ensure the document is perfected. Both the security agreement and financing statement use the word property interchangeably. “… we need only consider the sufficiency of the description in the security agreement because the descriptions are identical in both documents.” (World Wide v.

Metropolitan, 1986) No notification is provided that accounts receivables are being used as collateral; therefore, it is not the obligation of another creditor, or reader of the agreement to interpret what is meant by World Wide’s ambiguous statements. It is World Wide’s obligation to define, and perfect the security so that any third party might understand.

The burden of perfection is placed expressly on World Wide. Since World Wide was ineffective in perfecting the security agreement and only supplied documentation which might support the interpretation of property as physical or tangible property (exhibit “A”) they cannot claim Metropolitan’s accounts receivables even more explicably when State Bank has already filed a clear financing statement and security agreement providing their intent to collateralize

Metropolitan’s accounts receivables per their financing agreement.

State Bank’s security agreement and financing statement is valid securitization of

Metropolitan’s accounts receivables. World Wide’s documentation is invalid. World Wide’s agreement is too vague to perfect their security interests in Metropolitan’s accounts receivables.

Since State Bank has a clearly superior financing statement and security agreement in regards to

Metropolitan’s accounts receivables the fact must be acknowledged that World Wide’s claim to

Metropolitan’s accounts receivables is invalid.

Case Questions

State Bank effectively established a secured transaction with Metropolitan collateralizing accounts receivables. State Bank did so by perfecting a security interest with a clearly stated security agreement. State Bank perfected their security interest as World Wide did not. State

Bank therefore has the right of repossession of Metropolitan’s accounts receivables.

There are remaining questions in this case that have not been answered. Most of which can be summarized by Chief Judge Popovich in his dissent. One, State Bank in 1982 received

World Wide’s financing statement. State Bank “failed to make inquiry when it made the loan and failed to discover what was already encumbered. It failed to exercise ordinary diligence in inquiring what property was already encumbered by the filed financing statement.” (World Wide v. Metropolitan, 1985) Two, State Bank simply needed to check the filings and make a proper inquiry. State Bank’s negligence and rash underwriting should not defeat World Wide’s prior secured interests. Lastly, Popovich points out Marsden does not sufficiently deter the argument that if Metropolitan so desired, there is nothing illegal in security all one owns.

Arguments not explicitly covered in this case are State Bank’s inability to define World

Wide’s financing statement. Furthermore, State Bank effectively increased liability for three parties by taking on a loan with Metropolitan because of negligence. Why is this question not covered in the Superior Court’s deliberations?

Conclusion

The facts of the case show that World Wide did not effectively perfect the financial statement and security agreement to include accounts receivables. Only supplemental description

of tangible assets were provided by World Wide in regards to claims on rights of repossession.

Metropolitan then in February 1982 eighteen months after initially executing a note with World

Wide creates another agreement with State Bank. State Bank’s agreement clearly covers accounts receivables and intangible assets where World Wide’s agreement does not. State

Bank’s agreement is filed on March 3, 1982 subsequently in fall of 1982 Metropolitan defaults.

In accordance with the facts of the case it is clear World Wide’s ambiguity was their downfall. It is very plausible that World Wide having prior business similar to Metropolitan only two years prior would possibly be a more capable owner than State Bank. In this case had World

Wide effectively perfected the financial statement and security agreement State Bank would have been liable at their own risk. Since World Wide was ineffective in the perfection of the note it opened itself to State Bank’s negligence at the cost of Metropolitan’s accounts receivables.

It is also plausible given the facts of the case an institution in State Bank’s position could have foreseen this exact situation playing itself out, and planed recovering Metropolitan’s accounts receivables solely. In the court proceedings it appears that State Bank is negligent, though an institution may have viewed this course of action as a savvy and shrewd business decision being a larger more solvent and liquid business entity in a position to acquire valuable assets. The ethics and morality of this case are not far reaching to say the least, in that what is most importantly demonstrating in this case is that effective understanding (or lack of) of the laws and rules used to implement legal securitization led to World Wide’s loss.

The facts of this case are clear and of little dispute. World Wide was negligent as it appears State Bank may have been negligent as well. My recommendation in the extent of the court’s ruling is in complete agreement. The eventual ruling is satisfying and just.

Bibliography i

Business Law: Legal Environment, Online Commerce, Business Ethics, and International Issues, 7 th

Edition (Henry

R. Cheeseman, 2010, pg. 432) ii

Cherne Industrial, Inc. v. Grounds & Associates, Inc., Minnesota, 1979 iii

373 N.W.2d 839 *1985 Minn. App. LEXIS 4633; 41 U.C.C. Rep Serv. (Callaghan) 1508: World Wide Tracers, Inc.,

Appellant, v. Metropolitan Protection, Inc., formerly Protection Technologies, Inc., Defendant, Metropolitan State

Bank, Respondent,; John Hole, et al., Respondents No. C6-85-443 Court of Appeals of Minnesota. Sept. 10, 1985 iv

Minnesota Statues Article 9 Chapter 336.9-203 v

Pennsylvania Superior at 489, 433, A2d at 1360 vi

384 N.W.2d 442 *1986 Minn. LEXIS 753; 42 U.C.C. Rep Serv. (Callaghan) 1573: World Wide Tracers, Inc.,

Petitioner, Appellant, v. Metropolitan Protection, Inc., formerly Protection Technologies, Inc., Defendant,

Metropolitan State Bank, respondent, John Hole, et al., Respondents No. C6-85-443 Supreme Court of Minnesota.

April 4, 1986