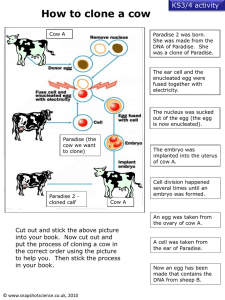

To Clone or Not to Clone

advertisement