Speech eBook - Santa Fe College

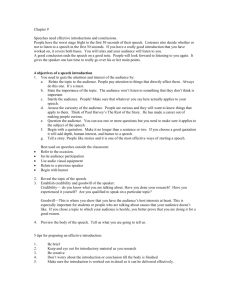

advertisement