Qld Office of the Public Advocate

advertisement

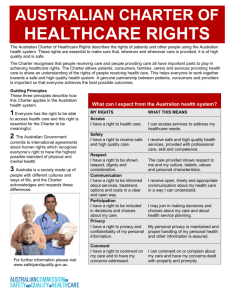

Submission by the Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland to the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission in regard to the recent consultation process July 2008 1. Interest of the Public Advocate The Office of the Public Advocate was created under the Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (GAA) to provide systemic advocacy for adult Queenslanders with a decisionmaking disability.1 Section 209 provides that the role of the Public Advocate is to: • promote and protect the rights of adults with impaired capacity for a matter • promote the protection of the adults from neglect, exploitation or abuse • encourage the development of programs to help the adults to reach the greatest practicable degree of autonomy • promote the provision of services and facilities for the adults • monitor and review the delivery of services and facilities to the adults.2 As outlined above, the functions of the Office of the Public Advocate (the Office) are, broadly speaking, to protect and promote the rights and interests of adults who have impaired decision-making capacity (IDMC). This cohort includes people with mental illness, intellectual disability, acquired brain injury and dementia. The Office makes comment to the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (NHHRC) to promote and protect the rights and interests of these adults. 2. Late comment The Public Advocate was invited to participate in the NHHRC consultation event held in Brisbane on 19 June 2008, and a representative of the Office attended. This Office, however, was not advised of the written consultation process and therefore was not able to make a formal submission before the deadline (30 May 2008). On enquiry, the Office was advised that written comments were still being accepted, and it is on this basis that the Public Advocate submits this brief paper for consideration. 3. Vulnerabilities of people with IDMC within the healthcare and hospital systems Despite the vast array of health and disability services available in Australia, adults with a decision-making disability experience high levels of unmet healthcare needs, are 1 2 Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld), Chapter 9. Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld), s 209. 1 succumbing to preventable illness at rates higher than the general population, and are dying earlier than other Australians.3 In addition, the health conditions of adults with IDMC, particularly people with intellectual disabilities, are either poorly managed or not recognised at all. Poor dental health is also more common amongst adults with IDMC.4 This cohort is particularly vulnerable when engaging with health and hospital systems. Their physical healthcare needs are often not easily identified, and there is a strong possibility that practitioner focus may remain on their underlying cognitive disability or mental illness; as a result, the physical illness often remains undiagnosed.5 As a result of these factors and many others, the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination6 is being compromised for people with IDMC. There are a number of other reasons why the physical healthcare needs of this group are not being met to the same standard as other Australians. Some of these reasons, as they fall within the proposed design principles for the NHHRC, are outlined below. 3.1 Communication difficulties Some people with IDMC have limited ability to communicate pain or describe their condition in ways that provide essential information for diagnosis. They may also have limited awareness about, or insight into, their physical wellbeing. As a result, health conditions can go undiagnosed and untreated. Untreated and poorly managed conditions easily deteriorate into chronic ill health, and may put people at risk of an early death. Furthermore, the current health care systems rely on the capacity of patients to communicate symptoms of ill health. This is not always possible for people with impaired capacity yet professionals typically interact with patients on this basis. Additionally, the system has little tolerance for individuals who are unable to communicate their distress in socially acceptable ways. As a result, individuals with limited communication strategies who communicate distress in unrecognisable ways or through confronting behaviour may be subject to sanctions or restrictive practices, or be banned from the services that are able to address their unmet need. An improved healthcare system will facilitate greater understanding amongst professionals about the communication needs of this group, and how to more appropriately manage challenging behaviour. 3.2 Lack of ability to navigate the various elements of a complex health system 3 A Western Australian study, for instance, found that life expectancy is negatively correlated with the level of intellectual disability. See A H Bittles, B A Petterson, S G Sullivan, R Hussain, E J Glasson and P D Montgomery, ‘The Influence of Intellectual Disability on Life Expectancy (2002) 57(7) The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 470-2. 4 Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland, In Sickness and in Health: Addressing the Health Care Needs of Adults with a Decision-Making Disability (2008) 8-10. 5 See, for example, R Coghlan, D Lawrence, D Holman and A Jablensky, Duty to Care: Physical Illness in People with a Mental Illness (2001) Department of Public Health and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Science, University of Western Australia. 6 Refer to Article 25 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities <http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf> at 23 July 2008. This convention was ratified by Australia on 17 July 2008. 2 For people who have affective or cognitive disorders, the current complexity of healthcare and hospital systems effectively acts as a barrier to accessing appropriate healthcare. Navigating complex structures and systems may be impossible for this cohort without considerable assistance. It is therefore essential that the system be simplified; that information is provided in ways that people with decision-making disabilities understand; and assistance is provided for people to access the services they need. 3.3 The need for additional supports Adults in this population may require support to ensure that preventative checks, vaccinations and specialist health care needs are undertaken and addressed. Without essential support, this cohort may be unable to managed their health, and may succumb to preventable illnesses or die. It is therefore imperative that healthcare systems do not situate themselves apart from other aspects of people’s lives such as the mechanisms and people that support them. There needs to be improved and increased interconnectedness between health and hospital systems, and the systems that support vulnerable adults. 3.4 Healthcare decisions are made by the appropriate substitute decision-maker People with IDMC for a health matter require decisions about that matter to be made by a substitute decision-maker. Health care professionals may not be aware of this fact, or may not be aware that the patient has impaired capacity for the healthcare matter. As a result, appropriate consent for treatment, as required under the GAA, may not be obtained. Also, the patient may not have the capacity to enact the required treatment and health care regimens. If the treating professional does not recognise this lack of capacity, the person’s wellbeing is potentially highly compromised. It is therefore important that healthcare providers and professionals be able to identify impaired capacity, and be fully aware of their obligations under the GAA. 3.5 Over-reliance on ‘shared responsibility’ It is one of the functions of this Office to encourage the development of programs to help adults with IDMC reach the greatest practicable degree of autonomy, and thus supports the proposal that people be empowered to manage the full range of their health needs, and that mechanisms be put in place for them to do so.7 Ideally, health providers and patients should work together wherever possible, and maintain an understanding about what each group has responsibility for. However, if healthcare professionals expect that people with IDMC should be able to manage their own health conditions, especially where they have impaired capacity for the healthcare matter in question and do not have any formal or informal support to do so, this inappropriate and misguided expectation may result in a significant deterioration in the person’s health. The Office therefore recommends that the risks associated with proposed design principle 3 (shared responsibility) need to be more fully explored in relation to this cohort. This principle should be reworded to acknowledge that some people may have limited capacity to manage responsibilities with regard to their health status, and that proposed design principle 7 In proposed design principle 3 (shared responsibility) the statement is made: “The health system has a particularly important role in helping people of all ages become more self reliant and better able to manage their own health care needs.” 3 1 ( people and family centred)8 be the priority in such instances. A medical professional, for instance, may need to ensure that the person is able to understand and undertake the required actions regarding healthcare routines and treatment regimens. Ideally it would involve ensuring that comprehensive and/or ongoing support is in place to follow through with directions from health care professionals and to maintain health. This last point requires the healthcare system to be well connected to supports and structures of benefit to adults with IDMC (as referred to in section 3.4). If the NHHRC is serious about improving the existing system responses to this cohort, it must ensure this occurs. 4. General comment on the proposed principles to shape Australia’s health system 4.1 Acknowledgement of the need for guiding principles The Office of the Public Advocate supports the development, implementation and monitoring of a set of carefully considered, evidence-based principles to shape Australia’s health system. At 15 July 2008, 15 principles have been identified by the NHHRC for possible inclusion in the reform framework.9 The principles appear to cover a wide range of elements that are fundamental to a sound health system. For instance, proposed principle 1 states that: “The direction of our health system and the provision of health services must be shaped around the health needs of individuals, their families and communities.” A system designed to respond to individual needs is more likely to be able to accommodate the often complex needs of people with IDMC. However, as indicated in section 3.5 of this paper, much work still needs to be done to flesh out the implications of these principles for people with IDMC. 4.2 Issues of equity for people with IDMC This office argues that the principles, as they are currently written, do not make sufficient reference to people, particularly adults with IDMC, whose additional vulnerabilities make them more susceptible to poor health and inadvertent exclusion from healthcare systems. For instance, proposed design principle 2 (equity) includes the statement: “The multiple dimensions of inequality should be addressed, whether related to geographic location, socialeconomic status, language, culture or indigenous status.” This statement is currently exclusionary and inadequate, and should incorporate a reference to the abilities/capacity or disabilities/lack of capacity of people. The relative inequity of the situation of people with IDMC also needs to be recognised. Proposed design principle 2 implies that particular attention needs to be paid to improve the health status of severely disadvantaged groups: it outlines the need to work with Indigenous people to “close the gap between indigenous health status and that of other Australians”. Given the demonstrated, considerable gap between the health status of people with IDMC 8 Proposed design principle 1 includes the statement: “The direction of our health system and the provision of health services must be shaped around the health needs of individuals, their families and communities. The health system should be responsive to individual differences…” 9 Refer to <http://www.nhhrc.org.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/principles-lp>. 4 and other Australians,10 the Public Advocate argues that, according to the equity principle, this cohort should also be considered a high priority in the NHHRC reform process. 4.3 Developing a system for vulnerable Australians It also needs to be noted that people with IDMC are more likely than the general population to require healthcare and treatment.11 Furthermore, this group of people constitute a significant proportion of the general population. Of society in general: • 1% live with dementia12 • 2% have an intellectual disability13 • 1.6% of women and 2.2% of men have an acquired brain injury14 • 20% of the population will experience a mental illness in their lives, and 3% have a severe mental illness at any one time.15 Therefore, up to 25% of the population may experience some degree of IDMC in their lifetime. This cohort, therefore, constitutes a significant proportion of the population accessing the health and hospital systems. Additionally, as implied within the equity principle, other relatively vulnerable groups also require focused effort to ensure that their healthcare needs are fully addressed. These groups include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (2.5% of the Australian population16), aged Australians (13%17), and people with a physical disability (approximately 16%18). While there exists some overlap between these groups (for example, some aged people have a physical disability), these figures indicate that the number of vulnerable Australians accessing health and hospital systems forms a substantial proportion of the population. Because of an increased probability of ill health, it is likely that they also constitute an even higher proportion of healthcare service users. 10 Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland, In Sickness and in Health: Addressing the Health Care Needs of Adults with a Decision-Making Disability (2008). 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. p. 8. 13 Ibid. p. 8. 14 Australian Government - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Media Release: Acquired Brain Injury Severely Affects 160,000 Australians <http://www.aihw.gov.au/mediacentre/1999/mr19991222.cfm> at 22 July 2008. 15 Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland, In Sickness and in Health: Addressing the Health Care Needs of Adults with a Decision-Making Disability (2008) 8. 16 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4705.0 – Population Distribution , Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/b06660592430724fca2568b5007b8619/14e7a4a075d53a6cca25694 50007e46c!OpenDocument> at 22 July 2008. 17 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 3235.0 - Population by Age and Sex, Australia, 2006 <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3235.0Main%20Features32006?opendocument &tabname=Summary&prodno=3235.0&issue=2006&num=&view=> at 22 July 2008. 18 Estimate is based on figures obtained from Physical Disability Council of NSW website – refer to <http://www.pdcnsw.org.au/education/_definitions.html> at 22 July 2008. 5 It is therefore evident that the proposed design principles and, in fact, the entire reform process, should have a strong orientation towards addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, rather than taking the perspective that most people who access the system do so from an advantaged, able-bodied or cognitively functional position. This Office therefore argues strongly for the incorporation of a vulnerable persons framework for the NHHRC reform project. 4.4 Developing a coordinated health and hospital systems At this point the Office notes other work that is currently being done to improve the current healthcare system by other agencies in jurisdictions across Australia. An example of this is the recent consultation undertaken by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care regarding the draft National Patient Charter of Rights (the Charter). This work is directly applicable to the NHHRC process, and the finalised Charter could be of value to NHHRC. (A copy of the Office’s submission to this consultation process is located at Appendix A of this submission for the NHHRC’s information.) The value of a coordinated healthcare system cannot be underestimated. This Office therefore recommends that the NHHRC undertake a thorough review of other health reform initiatives being undertaken across Australia, and, where appropriate, incorporate the findings from these pieces of work into the reform process. It would be to the detriment of healthcare users if the NHHRC missed opportunities to coordinate important components of Australia’s health system and close some of the systems gaps that currently exist. This Office also strongly urges the NHHRC to create a design principle that highlights the need for a comprehensive healthcare and hospital system that coordinates the multiple, disjointed healthcare responses that currently exist. 5. Work undertaken by the Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland on the issue of physical healthcare needs of adults with a decisionmaking disability The Office has recently published a discussion paper, In Sickness and in Health: addressing the health care needs of adults with a decision-making disability, that explores the issues associated with the physical healthcare of adults with IDMC. This embargoed paper19 highlights the physical health and dental needs of this cohort; identifies systems inequities faced by individuals with impaired capacity; and proposes ‘an agenda for action’ to improve Queensland’s healthcare responses to these adults. The action agenda proposes the following as priorities, and suggests the NHHRC considers these points in its reform process. • Development and implementation of targeted health education and promotion strategies across the systems and support networks involved in the care of people with decision-making disabilities. • Establishment and maintenance of simplified and timely access to low-cost health care services, including dental services. 19 It is expected that this paper will be publicly launched in August or September 2008. A copy of this paper will be forwarded to the NHHRC as soon as it is released. 6 • Development and maintenance of effective systems within formal support services to ensure that health care is a priority, and that people’s health care needs are met to a high standard. The widespread promotion and dissemination of health promotion and maintenance tools such as CHAP20 for use by support personnel within funded services is recommended. • Significantly improved and increased training for disability support workers in health promotion and management of health care, and in community connectedness for service users. • Improved and increased resources and support for family and support networks of people with decision-making disabilities. • Improved and increased education and support to health and allied health professionals regarding the needs of people with impaired decision-making capacity (with particular attention paid to GPs as a key access point for people seeking health care support). • Quarantined funding to cover the additional costs of ensuring high-quality health care support to people with impaired decision-making (for instance, the adjustment of the Medicare Benefits Schedule to accommodate the additional time required to consult with a person with impaired decision-making capacity). • Improved support for people with decision-making disabilities to make their own health care decisions when possible and appropriate. Systems need to ensure that decision-making for health matters within the context of service provision is undertaken by appropriate decision-makers.21 This office also argues that improved health outcomes for adults with IDMC are more likely to occur where all stakeholders work together to address the complexity of needs of this group. It is therefore imperative that hospitals and the health system are closely linked to, and form strong collaborative partnerships with, a number of other systems and agencies including, but not limited to: • healthcare providers across a range of disciplines • providers of associated services, including disability services, supported accommodation, corrective facilities, aged care residential facilities, rehabilitation facilities etc. • educators of healthcare professionals and professional associations; disability/support agencies; and people with IDMC and their carers 20 This program was developed by the Queensland Centre for Intellectual and Developmental Disability with the aim of promoting a comprehensive health assessment and plan for adults with intellectual disability. Refer to <http://www.som.uq.edu.au/research/qcidd/files/chap.pdf> at 23 July 2008. 21 Office of the Public Advocate – Queensland, In Sickness and in Health: Addressing the Health Care Needs of Adults with a Decision-Making Disability (2008) 33-4. 7 • policy makers and funding bodies that are linked to health, such as disability services • advocates and guardianship bodies • regulators such as the Anti Discrimination Commission and the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission • informal systems of care including families, support groups and carer organisations. Without strong partnerships across sectors and stakeholders, and a commitment to enact practices that promote the rights and interests of adults with IDMC, it is likely that this group of people will continue to suffer poor health and die earlier than they should. 6. Final comment The Public Advocate urges the NHHRC to establish reforms and develop systems that ensure the physical healthcare needs of the many adults with IDMC who access health and hospital systems are met to the same standard as other Australians. Since this cohort and other vulnerable groups form a sizeable proportion of the health system’s target group, they should be kept at the forefront of the NHHRC reforms to ensure that they no longer experience poorer health and die earlier than other Australians. 8 Appendix A Submission by the Office of the Public Advocate-Queensland To Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care Draft National Patient Charter of Rights March 2008 Interest of the Public Advocate The Office of the Public Advocate was created under the Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 to provide systemic advocacy for adult Queenslanders with a decision-making disability.22 Section 209 provides that the role of the Public Advocate is to: • • • • • promote and protect the rights of adults with impaired capacity for a matter promote the protection of the adults from neglect, exploitation or abuse encourage the development of programs to help the adults to reach the greatest practicable degree of autonomy promote the provision of services and facilities for the adults monitor and review the delivery of services and facilities to the adults.23 As outlined above, broadly the functions of the Office of the Public Advocate are to protect and promote the rights and interests of adults who have impaired decision-making capacity (IDMC). This cohort includes people with mental illness, intellectual disability, acquired brain injury and dementia. The Office makes this submission to the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) to promote and protect the rights and interests of these adults. General comments about the Draft National Patient Charter of Rights (the Draft Charter) The Office of the Public Advocate supports the development, implementation and monitoring of a National Patient Charter of Rights. As a general observation, it is considered that the Draft Charter adopts an appropriate tone. Some suggestions are made below for improving the suitability of the Draft Charter and Principles for adults with IDMC. It is suggested that the Draft Charter does not sufficiently cater for health service users who have IDMC. A significant proportion of the population is comprised of people living with mental illness (approximately one in five Australians will have a mental illness during their lifetime), dementia (increasing along with the ageing population), acquired brain injury, and with intellectual disability (people in this cohort are now living longer than in previous generations) some of whom will have IDMC for at least some health care decisions from time to time. Accordingly, people with IDMC comprise a significant portion of the client base of health service providers. It is suggested that the Draft Charter should recognise this reality. This could be achieved in the overarching statements made in the preamble to the Rights. 22 23 Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld), Chapter 9. Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld), s 209. 9 Specific comments are made about the articulated Rights and Principles and the explanatory comments in respect of each. References are made to Queensland legislation: each state and territory has its own arrangements. The numbering and headings in the Draft Charter are adopted in this submission for ease of reference. Accordingly, each is not repeated in full and the Draft Charter and this submission must be read together. Patient Rights and the Explanation of Each Right 1. Access Complex and subjective judgments are regularly made by health service providers about distribution of treatments which are in limited supply and in respect of which access is therefore limited. Notions of distributive justice are relevant. According to the Draft Charter, such treatments should be distributed according to clinical need. Given that in some cases, the need allocated will mean the difference between life and death, the issues are serious indeed. Unfortunately, not uncommonly, people with disability and especially IDMC have reported/experienced subjective judgments of health professionals and others, that their lives are not worth living because of their disability. Quality of life judgments are made by health professionals to inform decisions about who receives scarce treatments and who does not. People with IDMC are often unable to complain if they are disadvantaged in such processes and the consequences may be dire. This may be so despite the person with IDMC living a good quality of life. It may be difficult for health professionals with little understanding or experience of the lives of people with disability to understand that quality of life is not necessarily dependent on intellectual and/or physical prowess. Accordingly, it is suggested that the Draft Code be amended to clarify that people with IDMC are not to be disadvantaged when resource distribution is considered. 2. Respect It is undoubtedly the case that the most effective way for patients and health providers to interact is in a spirit of cooperation and mutual respect. However, adults with IDMC sometimes behave in a way that may appear disrespectful as a result of their impairment. Health service providers should be well placed to recognise their limited ability to comply with a requirement for mutual respect and consideration. Nevertheless, anecdotally, it appears that this is often not so. To be useful, the Draft Code must articulate clearly an understanding that people with IDMC are in a different position and cannot be expected to comply with such requirements when their capacity does not allow them to do so. Health service providers must understand and acknowledge that this is so and services must cater for the needs of this group, who by virtue of their conditions causing IDMC (which often also predispose the person to other conditions) may require more regular health care than many members of the general population who do not have IDMC. 3. Safety No comments. 4. Communication 10 To be useful, and able to be acted upon by patients, communication must occur and information must be presented in a format which the patient can understand and is appropriate given the characteristics of the particular patient. For many people with IDMC, some conventional approaches to communication and provision of information will be of limited use and could not be considered meaningful communication to the health service user. There must be some reasonable adjustment to information provision made in practical terms. This must be recognised and provided for generally in the Draft Charter as a responsibility of the health service provider. Language per se is not the only issue. Anecdotally, it seems clear that health service providers are not infrequently unable, presumably due to inadequate professional training and/or interpersonal skills, to communicate in a meaningful way with adults with IDMC. Rectifying this system deficiency probably requires at least significant changes to tertiary curricula and continuing education programs which are outside of the ambit of the Draft Charter. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile establishing standards about appropriate communication within it, for the benefit of both health service users and providers. 5. Information Again, information must be provided in a format and style which is useful and appropriate given the characteristics of the health service user, including health service users with IDMC. Information may be given for different purposes. It is necessary to inform decisionmaking by a health service user. In the case of a person with IDMC, this may not be the health service user personally- a guardian, enduring attorney for health matter or a statutory health attorney may be the decision-maker. Comments made below (in respect of the right of participation) about the nature and extent of the information which must be given are relevant. When information is provided to the decision-maker to inform the helath care decisionmaking process, the actual patient must nevertheless be prepared for the procedure to be undertaken, so meaningful and respectful communication and provision of information to the actual patient remains essential. There would be limited usefulness in providing a highly technical explanation in medical terminology of, for example, a proposed complex surgical procedure to a person with significant cognitive impairment. The manner and format of the communication should be respectful of the health service users’ characteristics. 6. Participation The right to autonomy or self-determination is fundamental to health law.24 At common law, a patient who has capacity may refuse treatment, even life-saving treatment.25 A patient with 24 Re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1, 72 E; Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] AC 789, 864C; Re A (Children) [2000] Lloyd’s Rep. Med 425, 494. See also discussion about the history of development of autonomy as a central idea in medical law, for example, in Derek Morgan and Kenneth Veitch, Being Ms B:B, Autonomy and the Nature of Legal Regulation [2004] Syd. L Rev 6 http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/disp.pl/au/journals/SydLRev/2004/6.html/query=gaa. 25 Patients who have capacity decide for themselves whether to accept or refuse recommended medical treatment, not their doctors. The right of a person with capacity to refuse treatment has been recognized in a variety of jurisdictions including the United States (Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital 105 NE 92 (NY) 1914)), Canada (Nancy B v. Hotel-Dieu de Quebec (1992) 86 DLR (4th) 385; Ciarlariello v. Schactr (1993) 100 DLR (4th) 609 (SCC); Malette v. Schulman (1990) 67 DLR (4th) 321), New Zealand (s. 11 Bill of Rights; Re G [1997] 2 NZLR 201; Auckland Area Health Board v. Attorney General [1993] 1 NZLR 235); and the United Kingdom (Re B (Adult refusal of medical treatment) [2002] 2 All ER 449; Re C (Adult refusal of 11 IDMC has the same right.26 Under Queensland law, there is some limited statutory provision for health care to be provided without consent; for example, under the Mental Health Act 200027 and the Guardianship and Administration Act 2000.28 Under the common law, an exception to the requirement for consent exists in the case of necessity.29 There is doubt that the common law with respect to exception/s applies in Queensland.30 Accordingly, the drafting of the ‘right’ to participate in decision-making as articulated in the Draft Code appears misleading. More properly, in most instances health service users have the right to accept or refuse health care (rather than a right to participate in the decisions and choices about care). The reference in the explanation of the right to participation to informed consent is noted. The intention may be to convey to health service users the need to consider material information when making decisions about whether to accept or refuse health care. The level of sophistication of an individual patients understanding of their health situation will no doubt impact on the information they require to make the decision, but an appropriate level of information must be given by the health service provider to every patient about proposed health care.31 There are two separate legal concepts which appear relevant in respect of this articulated right and the explanatory comments. Firstly, a valid consent must be obtained or giving of health care will potentially represent a trespass to the person, for which there may be civil and criminal law consequences.32 To be valid, as discussed earlier the person must have capacity to give it. It must also be voluntary33 and must cover the procedure undertaken.34 However, even though a consent may be valid, if insufficient information is provided to the medical treatment) [1994] 1 All ER 81; Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] AC 789; Re T ( Adult: refusal of medical treatment) [1992] 3 WLR 782. In Australia, there has been scant judicial confirmation of the common law position. However, it appears to have been implicitly accepted by the High Court in Secretary, Department of Health and Family Services v. JWB and SMB (1992) 106 ALR 385 (‘Marion’s Case’) 390,392 (where the majority endorsed the principle of bodily inviolability) and by the Queensland Supreme Court in Re Bridges [2001] Qd R 574. Ambrose J (when declaring that an adult did not have capacity to make decisions about health matters,) appears to have accepted a common law right to refuse treatment. 26 Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] AC 789. Lord Goff quoted with approval Superintendent of Belchertown State School v Saikerwicz26 [1977] 370 NE 2d 417, 428 in which the Supreme Court of Massachusetts said: To presume that the incompetent person must always be subjected to what many rational and intelligent persons may decline is to downgrade the status of the incompetent person by placing a lesser value on his intrinsic human worth and vitality. 27 This legislation provides for the treatment of people meeting the requirements of the Act without consent: Mental Health Act 2000 s 517. 28 See ss 62-64 in respect of urgent and minor or uncontroversial health care. 29 Re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1. Some academics argue that the common law also provides for exceptions in respect of other circumstances, for example, Loane Skene Law and Medical Practice: Rights, Duties Claims and Defences 93-97; 115-116. 30 Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 prescribes an offence for giving health care to an adult with IDMC other than as provided for in that Act: s79. 31 Rogers v Whittaker [1992] HCA 58. 32 Department of Health and Community Services (NT) v JWB (Marion’s Case) (1992) 175 CLR 218 at 232. 33 For example, see Norberg v Wynrib (1992) 92 DLR (4th) 449 (Can SC); Appleton v Garrett (1997) 8 Med LR 75. 34 For example, it is suggested that consent to a hysterectomy for endometriosis would not constitute consent to an abortion. See for example, Rogers v Whittaker [1992] HCA 58 12 patient about the material risks, the patient may have an action against the health care provider in negligence in the event of an adverse event.35 In respect of negligence actions in the leading case of Rogers v Whittaker 36, the High Court of Australia said 15. ….Anglo-Australian law has rightly taken the view that an allegation that the risks inherent in a medical procedure have not been disclosed to the patient can only found an action in negligence and not in trespass; the consent necessary to negative the offence of battery is satisfied by the patient being advised in broad terms of the nature of the procedure to be performed ((37) Chatterton v. Gerson (1981) QB, at p 443). In Reibl v. Hughes the Supreme Court of Canada was cautious in its use of the term "informed consent" ((38) (1980) 114 DLR (3d), at pp 8-11). 16. We agree that the factors referred to in F v. R. by King C.J. ((39) (1983) 33 SASR, at pp 192-193) must all be considered by a medical practitioner in deciding whether to disclose or advise of some risk in a proposed procedure. The law should recognize that a doctor has a duty to warn a patient of a material risk inherent in the proposed treatment; a risk is material if, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient's position, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it or if the medical practitioner is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it.37 This duty is subject to the therapeutic privilege. 38 Health service users cannot be expected to know what is meant by an alleged requirement on them to give informed consent. The health service provider must provide the material information to the health service user, to place the user in a position to give informed consent. Unless the explanation refers to the relevant requirements, they will generally not understand what is meant. Also, it is to the benefit of health service providers to be clear about their obligations. These comments are also relevant to the right to information and the explanation about the information which must be given. In Queensland, when a health service user has IDMC for the health matter under consideration (unless limited exceptions apply),39 a health service user must seek the consent for the health care from the appropriate SDM. It is an offence to give health care to an adult with IDMC without authorisation.40 Most commonly, authorisation will be required to be obtained through consent. The Draft Charter does not appear to recognise these realities. It is suggested that a broad overarching statement could be added: perhaps, to the preamble to the rights which acknowledges the special position of people with IDMC, in the same way that reference is made to cultural and social diversity. 7. Privacy 35 Rogers v Whittaker [1992] HCA 58. Rogers v Whittaker [1992] HCA 58. 37 Emphasis added. 38 [1992] HCA 58 [15-16]. 39 For example, see Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 ss 62-64 in respect of urgent or minor and uncontroversial treatment; and Mental Health Act 2000 s 517. 40 Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld) s 79. 36 13 Unfortunately, anecdotal reports suggest that privacy requirements are frequently cited as a reason not to provide information to guardians and other substitute decision-makers who are the formally empowered decision-makers for an adult with IDMC, even though they can produce documentation confirming their appointment and who have a legislative right to obtain the information.41 In respect of statutory health attorneys who can make most health care decisions for adults with IDMC in Queensland and whose appointment occurs by operation of law (as opposed to appointment by a tribunal or under an enduring power of attorney),42this issue may be exacerbated. It would be proper to recognise the need for information to be given to substitute decisionmakers. 8. Redress The comments made earlier about information provision are relevant. To be an effective mechanism for people with IDMC, complaints processes must facilitate and support the person and their support network (if they have one) through the process. Without such an approach, the ‘right’ articulated is meaningless for this vulnerable group of people who will effectively be precluded from accessing and navigating the process. Once again, it is suggested that the Draft Charter should specifically acknowledge and provide for this vulnerable group. National Patient Charter Principles Again, it is suggested that people with IDMC and the role of substitute decision-makers should be recognised in the preamble. The comments made above in respect of each of the articulated rights are again relevant. The following additional comments are also made about the Principles. 1. Access Programs for promoting health and preventative screening are often not well used by people with IDMC. They are reliant upon others to access the services. Unlike people with capacity, advising them of the existence of the service, providing them with a brochure, or relying upon advertising of the programs will usually be inadequate as a means of facilitating access. Proactive responses from health professionals (and of course, others who support the adults) will likely facilitate greater take-up rates. It is suggested that support to access public health programs appropriate to meet the needs of adults with IDMC is another principle which the Draft Charter could adopt. 2. Respect As noted, people with IDMC may not, and may not be always able to, accord respect dignity and consideration to their health care providers in the usual manner. This should not affect the regard a health care provider shoes the patient, or affect the provision of appropriate care and treatment. 3. Safety No comments. 41 42 See for example, Guardianship and Administration Act 2000 (Qld) s 44. Powers of Attorney Act 1998 (Qld) ss62-63, 75, 81. 14 4. Communication In keeping with comments made above, information should be provided, not only in a language that is understood, but in a manner that is meaningful and can be understood (of course, it is acknowledged that there are different levels of understanding) having regard to the characteristics of the recipient, including adults with IDMC. 5. Information Again, the role of substitute decision-makers for adults with IDMC could be usefully acknowledged. The role, as discussed above, is fundamentally different from the role played by support persons. The expectation that adults with IDMC will follow plans ‘as agreed with the health care provider’ will, at least sometimes, be unrealistic, unless adequate support is available or provided to the adult. The Principles could usefully alert health care providers to this and provide for such support as may be available through the public health system to be made available. 6. Participation Please note again the comments above about the right to accept (consent) or refuse health care and material information which will inform decision-making. It is suggested that some amendments are required to the current wording to reflect this position. Also, it is again suggested that the role of substitute decision-makers should be specifically acknowledged. They have a different role to play than ‘family, carers or other nominated support people.’ A person with capacity may well have support people, as will adults with IDMC. The same people will not necessarily be substitute decision-makers (although sometimes they will be). 7. Privacy Please note comments above. It is suggested some rewording is required to adequately address the requirement for information to be made available in appropriate circumstances to substitute decision-makers. 8. Redress As discussed above, it is suggested that the principles should include provision of support for vulnerable adults if it is to be a meaningful right for adults with IDMC. Rights and Responsibilities It is suggested that in most respects (comments have been made specifically above where considered not so) an appropriate balance between roles, rights and responsibilities is struck by the Draft Charter. No greater emphasis on patient responsibilities is warranted. Where greater responsibilities of patients are articulated (in other codes), it is sometimes suggested that health service provision is contingent on the health service user fulfilling their responsibilities. There are often no existing legal obligations on patients in accordance with so-called responsibilities. The approach has no legal basis. It is of particular concern when the articulated responsibilities may be such that vulnerable people with IDMC may not be able to understand that there is a responsibility, and yet may 15 be at risk of being refused service because they cannot comply. By virtue of psychotic or manic symptoms, intellectual disability, dementia or traumatic brain injury, a person may behave in ways that are undesirable and difficult to manage. In a person with intellectual disability, aggression may be a means of communicating extreme pain. In a person with mental illness it may be a result of symptoms of psychosis. A person in such circumstances is not less deserving of appropriate health care, than someone who has read and complied with a Code of expected behaviour. In such circumstances, substitute decision-makers and support people do not have a role or the power to ensure the responsibilities is met (notwithstanding that support people may use their best endeavours to achieve compliance). To be useful, the Draft Charter must articulate clearly an understanding that people with IDMC cannot be expected to comply with such requirements when their capacity does not allow them to do so. Health service providers must understand that this is so and services must cater for the needs of this group, who by virtue of their conditions causing IDMC (which often also predispose the person to other conditions) may require more regular health care than many members of the general population who do not have IDMC. It would be of significant concern that the Draft Code could apparently act to provide a basis for health service staff to deny or delay treatment to a person in dire need of it. Existing Charters Charters within Australia should support and be consistent with any National Charter. Otherwise, confusion will occur. Possible Uses of the Charter Good policy is often not translated into practice on the ground. A Charter, no matter how appropriate, which is not implemented will have no impact on service delivery within the health system and therefore be of no benefit. Accordingly, implementation is key. Implementation must be driven from the highest level. With respect to public health services, ideally, all Health Ministers would agree upon a National Patient Charter of Rights and undertake to implement it in their state or territory through development of consistent policy and practice. Then to ensure implementation, arrangements can be made for each health area manager and district manager (or equivalent) to assume responsibility for implementation and independent audits can be undertaken to assess implementation and drive continuous improvement. In respect of the private sector, responsibility for implementation will be more fragmented. Legislative amendment would be required to mandate adoption of the Charter and an auditing process with respect to compliance. Non-compliance could affect on-going accreditation and/or funding arrangements. The Charter could inform/underpin national standards of service delivery. How the charter applies in different sectors and settings Adaptation to meet the specific setting should be possible provided the guidance given by the Charter is sound and detailed sufficiently. However, if there is too much detail in the Charter, it will not be user friendly. 16 It is suggested that the Charter should properly be the document from which other policy work can flow, to provide additional guidance in respect of specific issues. 17