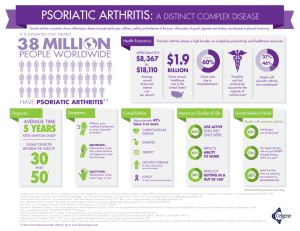

work disability in psoriatic arthritis

advertisement