Article Title: Nellie Bly's Account of Her 1895 Visit To Drouth

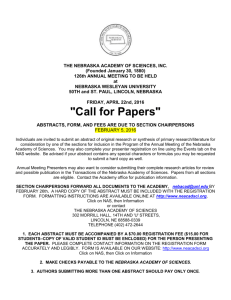

advertisement