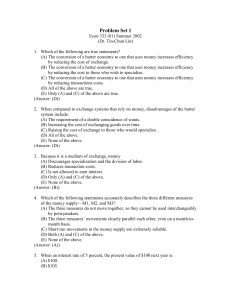

ARTICLE - Indiana Law Journal

advertisement