the origins of sale: lessons from the romans

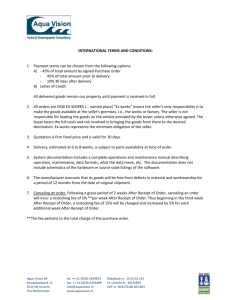

advertisement