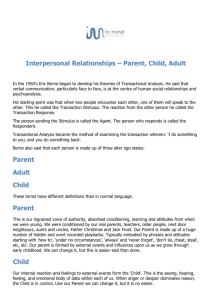

Transactional Analysis: Theory & Practice WebTutor Chapter

advertisement