Culture and Subcultures: An Analysis of Organizational Knowledge

advertisement

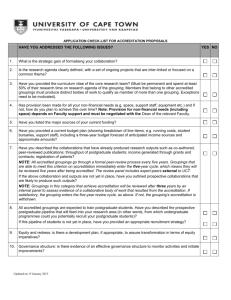

Culture and Subcultures: An Analysis of Organizational Knowledge Sonja A. Sackmann Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 1. (Mar., 1992), pp. 140-161. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28199203%2937%3A1%3C140%3ACASAAO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 Administrative Science Quarterly is currently published by Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/cjohn.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org Tue Dec 11 09:58:32 2007 Culture and Subcultures: An Analysis of Organizational Knowledge Sonja A. Sackmann Management Zentrum St. Gallen, Switzerland and University of Konstanz, Germany O 1992 by Cornell University. 0001-8392/92/3701-0140/$1.OO. . I am grateful to the president of BIND and all the people who have given me so much of their time. Many thanks to Dick Goodman and Maggi Phillips, whose comments and stimulating discussions have helped to sharpen my research, thinking, and writing. The suggestions made by three anonymous ASO reviewers and Gerald Salancik. Associate Editor of ASO, were very helpful in revising the earlier versions of this manuscript. This study investigated the potential existence and formation of subcultures in organizations, using an inductive research methodology to study the extent to which four different types of knowledge were shared by organization members. Fifty-two interviews were conducted in three different divisions of the same firm. These were content-analyzed and compared with data obtained from observations and written documents. A number of cultural subgroupings were found to exist in regard to two kinds of cultural knowledge, while an organization-wide cultural overlay was identified for a different kind of cultural knowledge. The implications for the concept of culture in organizational settings and future research on this topic are discussed.. INTRODUCTION Research on culture in organizational settings faces two major interrelated problems. First, little empirical knowledge is available about the concept in the context of organizations to guide research efforts. Second, the existing conceptual diversity makes it difficult to operationalize culture. Existing research on organizational culture has explored its components and structure primarily on theoretical grounds or empirically with deductive reasoning. While both approaches have their merit, some questions about culture remain unanswered. Is culture homogeneous (e.g., Davis, 1984; Schein, 1985)? Is it heterogeneous (e.g., Gregory, 1983; Martin, Sitkin, and Boehm, 1983; Van Maanen and Barley, 1985)? Or is it both (Martin and Meyerson, 1988)? If the latter is the case, which aspects of culture are homogeneous and which are heterogeneous? If culture is composed of subcultures (e.g., Handy, 1978; Louis, 1983; Jamison, 1985), where do they emerge and what triggers them to emerge? Given the sparseness of empirically based knowledge of organizational culture, an inductive research approach can provide valuable insights at this stage into its complexity (Van Maanen, 1979a). This paper describes one such inductive approach. Conceptualizing Culture in Organizations The concept of culture has been adopted primarily from the field of anthropology, where it has been defined in many different ways and from different perspectives (Kroeber and Kluckhohn, 1952). These have found their equivalents in the organizational literature (Smircich, 1983). Despite the different perspectives on culture in organizations, the focus on cognitive components such as assumptions, beliefs, values, or perspectives as the essence of culture prevails in the literature (e.g., Gregory, 1983; Dyer, 1985; Schein, 1985). Such an exclusive focus on cognitive components has its shortcomings (Martin and Meyerson, 1988: 96). Given that organizations are purposive, the manifestations of ideas in practices are important. Comparing expressed ideas and actual practices as perceived by others can provide valuable information about the world view of organizational members and its degree of overlap with reality as perceived or experienced by others. In a study of culture, observations of manifestations such as artifacts and behaviors can therefore be used as sources of data to "triangulate" with information obtained about cognitive components. 140/Administrative Science Quarterly, 37 (1992): 140-161 Culture and Subcultures Definitions of culture vary, however, in their use of a central concept. The central concept in use may include ideologies (Harrison, 1972), a coherent set of beliefs (Baker, 1980; Sapienza, 1985) or basic assumptions (Wilkins, 1983; Phillips, 1984; Schein, 1985), a set of shared core values (Deal and Kennedy, 1982; Peters and Waterman, 1982), important understandings (Sathe, 1983), the "collective will" (Kilmann, 1982: I), or the "collective programming of the human mind" (Hofstede, 1980: 25). These concepts are either used from a functionalist or an interpretative perspective, with culture being something that an organization "has" as compared with something an organization "is" (Smircich, 1983; Sackmann, 1989). In addition, different authors tend to use these concepts in different ways, creating some conceptual confusion and ambiguity (cf., Brown, 1976; Deal and Kennedy, 1982; Peters and Waterman, 1982; Davis, 1984; Schein, 1985). At this stage of theory development, it is unclear which one or which combinations of these frequently used concepts represent culture best. Instead of adding to this conceptual confusion by using one or several of them, I sought more generic constructs that would capture the essence of culture from an interpretative or cognitive perspective while reflecting the commonalities underlying the various concepts in use. In the tradition of the interpretative or cognitive perspective, the mechanisms for collective sense making are of particular interest. At the individual level, sense making is an activity in which individuals use their cognitive structure and structuring devices to perceive situations and to interpret their perceptions (Seiler, 1973). Important cognitive structuring devices are (1) the labels used to describe or name things or events, (2) explanations about an event structure, (3) "lessons," in the form of recipes and prescriptions for repair, and (4) reasons for the causation of events (Heider, 1958; Spradley, 1980). These four cognitive structuring devices, which I refer to here as cognitions, do not exist in isolation. Instead, they form an integrative and interconnected gestalt that has been variously labeled a scheme (i.e., Piaget, 19541, a plan (Miller, Galanter, and Pribram, 1973), or a cognitive map (Tolman, 1948). What differentiates collective sense making or cultural cognitions from individual ones is that the former are commonly held by a group of people in a given organization, even though members of the same cultural group may not be aware in their daily activities of what they hold in common. In the process of enculturation, cognitions become rooted in the group and ultimately exist independently of an individual group member, even though individuals are the carriers of culture (White, 1959). Similar to the individual cognitions that accumulate over time in the form of different kinds of knowledge (Schutz and Luckmann, 1975). commonly held cognitions accumulate in the form of cultural knowledge. Based on the structure described above, four different kinds of cultural knowledge can be differentiated and labeled: (1) dictionary knowledge, (2) directory knowledge, (3) recipe knowledge, and (4) axiomatic knowledge. 141/ASQ, March 1992 Dictionary knowledge comprises commonly held descriptions, including labels and sets of words or definitions that are used in a particular organization. It refers to the "what" of situations, their content, such as what is considered a problem or what is considered a promotion in that organization. As such, it reflects the semantics or signifiers (Broms and Gahmberg, 1987) that are acquired step by step (Schutz and Luckmann, 1975) in a particular cultural setting. While behaviors are located at Schein's (1985: 14) level of artifacts and creations, their attributed meanings are at a deeper level. One may therefore observe similar issues or manifestations in different cultural contexts with different descriptions, or similar descriptions may signify different issues, events, or manifestations when found in a different context. Directory knowledge refers to commonly held practices. It is knowledge about chains of events and about their cause-and-effect relationships. Directory knowledge delineates the "how" of things and events, their processes, such as how a specific problem is solved in a given organization or what people actually do to be promoted. It is similar to Fritz Heider's "Alltagstheorie" (everyday theory) or Argyris and Schon's (1978) theory of action. Directory knowledge is descriptive rather than evaluative or prescriptive. Recipe knowledge, based on judgments, refers to prescriptions for repair and improvement strategies. It expresses "shoulds" and recommends certain actions, how a particular problem should be solved or what a person should do to be promoted. Recipe knowledge contains prescriptive recipes for survival and success, is closely related to norms, and is similar to Argyris and Schon's espoused theory. Axiomatic knowledge refers to reasons and explanations of the final causes perceived to underlie a particular event. It represents premises that are equivalent to axioms in mathematics in that they are set a priori and cannot be further reduced. Axiomatic knowledge is about the "why" things and events happen, why a particular problem emerged, or why people are promoted in a given organization. Axiomatic knowledge is similar to Schein's (1985: 14) basic assumptions, but unlike Schein's levels of culture, these four kinds of cultural knowledge are all part of culture's essence or its core. Artifacts or behavioral manifestations are part of the culture network, not its core (Sackmann, 1983). Together, dictionary, directory, recipe, and axiomatic knowledge form a cognitive culture map. Within this perspective, artifacts and behavioral manifestations are considered expressions of culture located at a surface level. They are of interest in terms of their attributed meanings. These may reflect the underlying collective sense-making components accurately, but they may also be part of outlived routines that belong to a past era whose meanings are no longer relevant to the dominant group of organizational actors. In either case, the interpretation and understanding of their attached meanings in a given cultural 1421ASQ. March 1992 Culture and Subcultures context requires an inquiry into the underlying processes of sense making (Schutz, 1962; Goodenough, 1971; Fetterman, 1989). The above-described framework of cultural knowledge was applied and refined in a study designed to give new insights into how culture is structured in organizations: whether it is homogeneous or heterogeneous, consisting of subcultures, or both, and where any existing subcultures might be located. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Rather than hypothesizing about subcultures and their locations a priori, an inductive research methodology was chosen so that unknown groupings could emerge. This method permits better understanding of complex phenomena (Van Maanen, 1979a) from an emic, or insider's perspective (Evered and Louis, 1981). Using the above framework of culture, the methodology of choice needed to, first, reveal insiders' cognitions and cultural knowledge and, second, identify cultural groupings that might exist. Combined ethnographic (Van Maanen, 1979b). phenomenological (Husserl, 1975; Ihde, 1977; Massarik, 1977). and clinical methods (Schein, 1987) were used for data gathering. The methodology combined four components: (1) the method and sampling process derived from Diesing's (1971) method successive comparisons, which allowed the range of information collected to be successively narrowed to the final investigation of an emerging hypothesis, (2) the focal method for data collection consisted of interviews, which were complemented by observations in the research setting and by secondary data analysis, (3) theoretical (thematic) content analysis at an individual level and at a group level was used for data analysis, and (4) the results from the thematic content analysis were validated by comparing and contrasting them with data obtained from secondary data analysis and observations and by testing their validity with selected informants. An emerging hypothesis about cultural groupings was further examined by a focused replication of the research in an additional site. All data were objectified through dialectical discussions with two colleagues and by a reanalysis one month later. A mid-range methodology was developed to elicit culture-specific knowledge meaningful to insiders, but within a reasonable period of time (Sackmann, 1992). The core method for data collection was an open interviewing technique with an issue-focus (Dutton and Duncan, 1987). The issue-focus was chosen for three reasons: (1) to serve as a stimulus for eliciting culture-specific cognitions, (2) to channel and narrow the potentially broad exploration, and, (3) to introduce a reference point for respondents so that the information could be compared across time and events for each individual and across individuals. It is difficult to ask members directly about what they think their culture is. The issue-specific exploration served as a projective device to elicit context-specific cognitions. The selected issue had to have a broad connotative meaning to leave room for 143/ASQ, March 1992 culture-specific interpretations, be relevant to organizational members, and avoid systematic response biases. A discussion with organizational members about different issues, such as decision making, communications, leadership, or innovationlchange, indicated that the issue of innovationlchange qualified best. Pilot interviews revealed that it was perceived as relevant to most organizational members, that it was customarily defined, leaving room for culture-specific interpretation, and that it was unlikely to evoke systematic response biases at an individual level. To permit intraindividual comparisons, each person was asked to name the three major innovations/changes that had occurred in the company during the last five years. The reasons for and characteristics of the named innovationslchanges, including the related processes, were then explored in detail. After some warm-up questions about the person's work history, the exploration of innovationlchange started with a broad, open-ended question, followed by triggering questions (Spradley, 1980) that fit into the flow of the interview determined by the informant (Massarik, 1977). Simultaneously, I paid attention to the body language, gestures, or physical expressions and responded to them if there was a discrepancy or if they suggested urgency. During each interview, the following questions were asked and explored: Which three innovationslchanges that occurred during the past five years in the company do you consider most important? This broad question allowed informants to define (a) innovationslchanges, (b) relevancelimportance, and (c) their identity (function, division, firm, etc.). Then for each of the named innovations/changes: Why do you consider the mentioned innovationlchange important?; What was the context of the particular innovation?; Who was involved at what time and how?; What caused the innovationlchange?; Who and what aspects promoted the innovationlchange?; Who and what aspects presented obstacles in the process and how?; What shouldlcould have been done to improve the innovation?; What would you do differently in the future to make it better? I tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim all interviews to gain in-depth knowledge of the data. Research Sites Three different sites of a medium-size conglomerate (BIND) were chosen for the study: the corporate headquarters and two divjsians. At the time of the study, the firm consisted of twenty-nine divisions located in different regions of the U.S. It had $300 million in sales and $12 million in profit. The criteria of choice for the divisions were as follows: (1) all sites had to be located in the same region of the same country, to control for regional and national effects; (2) headquarters (corporate officers) would be included so that leaders' possible influence on organizational culture could be studied; (3) the selected divisions had to differ in terms of their business so that potentially similar cultural knowledge would not be attributable to the specific work or industry; (4) the two divisions had to employ a similar number of people, to rule out the influence of size, which influences the amount of contacts between people within and across hierarchies; and (5) the two divisions had to have belonged 144/ASQ, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures to the company for several years and approximately the same number of years so that the same amount of cultural knowledge could have developed. Corporate headquarters (HQ) employed twenty-five people, including eight executive officers, one of whom worked at a division in a different region. It is considered a division because people in the firm perceived it as a division rendering services to the other divisions of BIND. The PC division manufactured precision components, predominantly for computers and airplanes. It employed seventy-two people at the time of the study and had been a division of BlND for nineteen years. The GA division distributed graphic and art supplies, including large photo and copying machines. It employed eighty-two people and had been a division of BlND for sixteen years. Data Collection A total of fifty-two interviews were conducted over a period of four months with informants chosen either randomly or purposefully (Patton, 1980). The purposefully collected sample consisted of all of the seven executive officers who were regularly present in HQ, to account for a potential leader influence, and twelve informants who were selected from the GA division to investigate a hypothesis that emerged during the study (see below). Thirty-three of the interviews were conducted with individuals randomly selected across hierarchical levels and functions from the headquarters and from the PC division. The random sample permitted groupings to emerge from the data without the bias inherent in any stratification approach. A total of thirty interviews were conducted in the corporate headquarters and in the PC division. I obtained a good feel for the two divisions and their members' concerns through a grand-tour participant observation (Spradley, 1980) during the first visit in each site, the first interviews, and participant observations. I tested these early impressions during the interviews and in casual discussions while visiting the research sites. Analysis Two thematic content analyses, an individual and a group analysis, were conducted to analyze the interview data for all thirty interviews (Carney, 1972). Individual analysis. I analyzed each interview separately to identify emerging themes (equivalent meanings attributed to situations or events) across the three innovationslchanges that were named by each individual. I developed a system for condensing the interview data that was based on the four types of cultural knowledge and on a preanalysis of the thirty interviews. This system was further adapted during the subsequent data analysis. Each innovationlchange was analyzed separately by first marking the text and then by listing phrases that the individual used. I listed my inferences in brackets. Appendix A lists the rules I applied to the analysis of the interviews and gives an example of how the text of one individual was condensed, according to those rules, for innovation1 145/ASQ, March 1992 change #2. Appendix B gives an example of the condensed format of the other two innovationslchanges given by that same individual. The condensed data on all three innovation1 changes were then compared across innovations to arrive at more general statements, which were listed on a separate page and included emphasis, special concerns, and general attitudes (see Appendix B). Verbal expressions, tone of voice, and the frequency of mentioning a certain aspect were taken as indicators for emphasis. Each interview transcript, which averaged twenty-five single-spaced pages, was condensed in this way to relevant statements and organized into a few pages. The emerging themes or patterns were validated by (1) comparing the information on the three innovations for each individual, (2) comparing the emerging themes with the information obtained through observations and secondary data analysis of documents of and about the firm, and (3) checking the validity of the choice of themes with selected informants. Two additional procedures ensured that the data analysis was not entirely subjective: (1) I had hours of detailed discussion of themes with two colleagues who met with me for two to three hours twice a week during the period of the research project. Due to our different training, three different perspectives (strategic, technological, behavioral) were used dialectically to question the preliminary analysis, and (2) A reanalysis of a random sample of interview data was done one month later. No significant changes were found between the first and the second analysis. Group analysis. In a second step, the themes that emerged in each individual interview were compared across individuals to identify cultural (commonly held) themes that were held simultaneously by different people in the organization. Individuals were grouped together if (1) for similar reasons, they considered the same innovations1 changes important ones (dictionary knowledge), (2) the ways in which the mentioned innovationslchanges had happened (origin, and facilitating and hindering factors) were basically the same, regardless of the specific innovation (directory knowledge), (3) the improvement strategies or recommendations for innovationlchange were the same (recipe knowledge), and (4) the basic premises that governed their thinking, behavior, and feeling in their role as organizational members were the same (axiomatic knowledge). In this way, groups were created for each category of knowledge separately. In assigning individuals to groups, the first decision-rule was the "existence or not" of information. A group was initially created from respondents who had reported information in the same category. In regard to dictionary knowledge, respondents were grouped together if they had at least two innovationslchanges in common. For the other three kinds of cultural knowledge, two broad cutoff or threshold figures were used initially: one was 70 percent in common and the other was 50 percent. Thus, in the latter case, some people could be identified as members of an additional group. The actual data analysis showed, however, that the mentioned information was either very similar or 146/ASQ, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures very different. For this reason, no additional, more sophisticated techniques were used for clustering the data. The observations made in the research site were used as complementary data for the grouping decision. The observations included such things as work- and nonwork-related interaction patterns, verbal inclusions in or exclusions from a group ("we" vs. "they"), and nonverbal inclusions in or exclusions from a group, such as similar or different ways of dressing. These cultural themes were then validated and objectified in the same way as described above for the individual analysis. Validating Themes As a last stage, ten additional interviews were conducted at HQ and at the PC division to collect further information and to probe for the themes that had emerged in the content analysis. These interviews were also used to investigate further the discrepancies that had emerged from the data in the previous stage. These data were analyzed like the other interview data. During this stage, a hypothesis emerged from the data that cultural groupings may form according to functional differentiation. This hypothesis was subsequently tested by selecting a functional sample (marketinglsales) from a third division (GA) in which no interviews had yet been conducted. Twelve people were randomly chosen from this purposive sample (Patton, 1980) for interviews. The resulting data were analyzed, validated, and objectified as described above. One month later, a random sample of twelve full-length interviews was drawn from all interview transcripts. Each of them was reanalyzed for themes in dictionary, directory, recipe, and axiomatic knowledge. No significant changes emerged between the first and the second analysis. FINDINGS Altogether, nine cultural groupings were identified across the four kinds of cultural knowledge. Seven cultural subgroupings surfaced in regard to dictionary knowledge. Only one cultural grouping was found in regard to directory knowledge. This grouping spans all three divisions. Another grouping, which is restricted to the top-management group, was identified in regard to axiomatic knowledge. The information obtained about recipe knowledge did not clearly reveal any cultural groupings. Subcultures Formed around Dictionary Knowledge I identified seven cultural groupings that formed around dictionary knowledge, the "what is" of things and events. The analyses of the interviews as well as the observations in the research sites suggest that these cultural groupings exist according to functional domains, defined as the totality of functions for which people considered themselves responsible. Functional domains are tied to people's professional role perceptions and perceived responsibility in their professional roles rather than to such structural manifestations as departments or prescribed roles in an 1471ASQ. March 1992 organization chart. One of these seven groupings was temporary. with a membership that shifted according to the problems at hand. Most of the members that formed this temporary grouping were also members of one of the four groupings found in the same location. The specific interpretations of a group's functional domain tended to be influenced by hierarchy, by divisional identity, and, especially at lower levels, by the nature of the work or task. Functional domains that were located at a higher level of the company's hierarchy had a more general and strategic or design orientation than the functional domains located at a lower hierarchical level, which were specific and execution or implementation oriented. Across divisions, the same functional domains were, to some extent, enacted differently by the members of different divisions. The data also suggest that corresponding functional domains of different divisions are more similar than different functional domai!s within one division. The two groupings of the same functional domain across divisions had more in common than the different functional domain groupings found within one single division. The seven functional domain groupings found within the three sites of BIND were as follows: a design and control grouping at the top-management level; two managerial marketing groupings (one in the PC and one in the GA division); a coordination grouping, and three different production groupings in the PC division. Table 1 shows the number of members in each grouping and the percentages they represent of the division, of the total sample, and of the people performing that particular function in their division. Organizational design and control grouping. The design and control grouping consisted of seven members who were located at the HO division. Interviews revealed that their major innovations/changes dealt with strategic and control issues, such as to "build and maintain a successful company" through internal and external "controlled profitable growth." As such, the design elements of the "corporate structure" were important to them, such as the "computer system," "standardized accounting and human resource systems," "autonomy of the divisions," the "operations group," or "centralized finances." Of importance Table 1 Cultural Groupings by Dictionary Knowledge* Cultural grouping Design and control Production (Electronics) Production (Shopfloor) Production (Inspection) Marketing PC Division Marketing GA Division Coordination grouping * Sample: Size of group % of division % of total sample % of people performing that function 7 5 7 5 3 9 6 10 28.00 6.94 9.72 6.94 4.17 10.98 13.46 9.62 13.46 9.62 1.92 17.31 11.54-23.81 87.50 83.33 23.33 83.33 100.00 75.00 -4 -t HO, N = 10; PC Division. N = 30; GA Division. N = 12: total N = 52. t The percentage cannot be computed, since group members may come from different divisions. *The percentage cannot be computed, since people from other divisions perform this function but they are not part of this grouping. 148lASQ. March 1992 Culture and Subcultures also were strategic issues such as "selling unprofitable divisions," "profitable sales," or "expansion of markets." They were also concerned about the fair treatment of people, expressed by "provide opportunities," "give responsibilities," or "promotion from within." In addition, this group exerted various means of control to ensure that their intentions were being considered in decision making and in production-oriented work activities throughout the entire company. Production groupings. Production groupings consisted of various people involved in the production cycle. Three distinct production groupings were found in the PC division: Electronics (PE: N = 5), shopfloor production (PSF: N = 7). and inspection (PI: N = 5). Each subgroup was influenced by the nature of its particular work. This "local" orientation also differentiated each group from the others. All three groupings clearly distinguished between "we" and "them." This distinction was supported by my observations of ther57: They dressed differently, and they worked in distinctly different work spaces that were furnished differently. They took separate breaks during the day, and the tone in which they interacted varied in its degree of roughness. Their d i c t i ~ n aknowledge r~ in regard to innovations/changes was tied to their kind of work, their work environment, and to specific people. The PE group talked about "job security," a "small company," and "health and dental insurance." The PSF group talked about "more work," "upgrade of assembly," and "being in control of the job." Themes in the PSF group were orientation toward people, growth of the division/company, and strategy. The PI group mentioned an "expanded inspection department," "improvements in quality control," the "quality control system," or "partnership." Some themes in the group were growth of the division/company and orientation toward people. Managerial marketing and managerial sales groupings. The three members of the managerial marketing group were concerned with strategy and the marketing of PC division's products (N = 3). They had "identified a niche" and accomplished their goal by "identify[ingl new products that they could produce for customers," by "educating customers" about the division's capacities, and by "acquiring new customers" for existing or new products. These were all expressions of a strategy theme. At the GA division, the equivalent grouping was more concerned with selling existing products (N = 9). Their guiding principle was "offer the customer peace of mind," a strategy theme. Controlled profitable growth was accomplished through "creating new opportunities for sales" by expanding both their services and their existing product lines. The members of both groupings showed a strong entrepreneurial--or, rather, intrapreneurial--orientation that was reinforced by the divisions' reward structure. The group members' differences in interpretation of their roles were due to differences in their divisions' businesses. The PC division was a job shop producing parts to customer 149lASQ. March 1992 specifications, while the GA division was a distributor for several manufacturers. Coordination grouping. A coordination grouping was found at the PC division. Its membership varied from six to ten, according to the task or project at hand. It was generally created around a problem that had emerged as, for example, buying computer numerical control machines. Thus, it was a grouping with temporary and shifting membership, and its members simultaneously belonged to other groups as well. Usually, the coordination grouping consisted of the general manager, the plant manager or plant supervisor, one of the engineers, one of the sales people, and one of the production control people. Other individuals who could be part of this group were the vice president in charge of this division, the controller, the manager of the electronic subsystems, and/or the quality control manager. This group's major concerns were to coordinate projects and the exchange of ideas and information between people with internal concerns (production) and external concerns (salespeople, customers). Its foci varied from general planning and decision making about investments to specific problem solving. Hence, the members of this grouping had boundary spanning roles when they acted as members of this group. Homogeneity through Directory Knowledge The same cultural groupings found in regard to dictionary knowledge did not emerge in the analysis of directory knowledge, the commonly held cognitions concerning knowledge about processes. Instead, a homogeneous cultural grouping emerged across the three divisions that had the quality of cultural synergy. Every member of the sample belonged to this grouping. Four common structural processes were found to underlie the actions of organization members across the three research sites, even though they acted independently of each other and did not know about the behavior of people in the other divisions, and even despite the fact that the three divisions were engaged in different businesses and that informants in all three divisions had a strong divisional identity, contrasting "us" to "them." They differentiated their divisions from other divisions on several occasions and believed that their division was more special than the others, although I found no evidence to support that. Despite all these differences, cultural synergy emerged across divisions in regard to directory knowledge. No matter which innovations/changes were reported as major ones, the underlying processes by which these different innovations/changes were achieved were basically the same across organizational members, across different cultural groupings, and across different divisions. The cultural grouping at this level included all three research sites and therefore can be hypothesized to be company-wide. The four culturally based processes were present in the responses of all respondents, regardless of division, tenure, function, or hierarchy. These processes were the ways in which tasks were accomplished, people related to each other, adaptation and change were accomplished, and new 1 SOIASQ, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures knowledge was acquired and existing knowledge perpetuated. To an outsider of BIND, the examples given below of enactments of these four processes may sound like cliches. However, to the people in the organization, they were unique and very real and important, since they addressed basic questions of their organizational existence. Accomplishing tasks. Throughout BIND, tasks were accomplished through both individual and team efforts. Individual employees made efforts in their own territory or field of competence and expertise, each contributing his or her special skills. "Take initiative and see that everything gets done" was mentioned by most respondents in one way or another. It served as a guideline for work behavior in BIND. These individual efforts, in which employees took pride, were integrated through teamwork to accomplish complex tasks or projects. Intrapreneurship was complemented by cooperation and by joint efforts, exemplified by such comments as "I'm only as good as the people behind me." In the PC division, for example, people would help each other out if they perceived a backlog at a machine. This autonomy created some problem for the general manager, who was relatively new in his position and tried to stem what he felt was a loss of control. Despite his control attempts, however, people sustained their autonomous team efforts. Relationships among people. Relationships among people within BlND and with customers could be characterized as informal, direct, open, and respectful. One of the informants, who had experience in other firms and industries, expressed it as follows: I know how a lot of companies are run and operate. I know a great majority of the companies in LA and Orange County just through my job. BlND is different from most companies. The attitude, the management style, . . . if you walk in this company and see him [the president] walk around, you wouldn't get the idea that he is the president and chairman of the board of a major corporation. He's a real [strong emphasis] person. . . . In companies of this size you do not see the president. And many of the VPs are kind of 'off limits' to most people. The doors are closed, they are in meetings. In this company it's very different, very casual. . . . Here you can be your own person. There are open communications. Everyone is treated equally. . . . I think that's a very innovative policy. . . . I feel like if I have something to say to anybody I can walk in that door. Numerous other manifestations could be found in verbal and nonverbal behaviors such as informal dressing, open doors, the floor plan at HQ, which was deliberately designed to invite informal interactions and discussion, which did occur frequently and spontaneously, the knowledge and use of first names, or social events on weekends, such as football games among employees, picnics, luncheons, and trips to Disneyland and to professional ball games. Verbal promises were followed by immediate actions. One employee expressed it as "we are very close, it's like a family," another as, "I couldn't ask for a better situation. I love [strong emphasis] working for this company. I love this company. It's my family life. I feel real close, good about it." This family orientation is sustained by the particular hiring policies. First priority was given to family members and acquaintances of employees, because those people already 151/ASQ, March 1992 had some knowledge of BIND. This family orientation was also validated by outsiders who worked with BIND, such as suppliers and customers, and by my own experience in the company. Adaptation and change. Adaptation and changes required by the business environment were accomplished through both conservative and innovative behavior, Innovative behavior was practiced in adaptation and internal changes, especially if these changes did not require financial resources, for example, improving or adjusting production procedures. Conservative behavior was shown whenever change or adaptation required substantial financial resources, as in introducing a computer system. The development of new procedures or products occurred through controlled and successive experimentation to minimize risk and instability within BIND. Changes were tried out and optimized before they were successively diffused to the rest of BIND. Acquisition and perpetuation of knowledge. In the divisions studied, new knowledge was acquired in three ways: (1) staying informed of changes in the industry by reading trade journals and by attending trade shows; (2) hiring people with the desired or necessary knowledge; and (3) having employees attend specific professional courses. Existing knowledge was perpetuated in two ways: through informal learning on the job and through coaching and mentorship. No formal training programs existed. New employees were expected to "swim" once hired and to take responsibility for their own learning. Promising employees and people in key positions were coached and given opportunities to learn and progress both personally and professionally. As one of the corporate officers (and former general manager) explained: "I'm always trying to plant seeds and then I'm waiting for people to come around, ah, I don't mean that in an egotistical sense, but I see that as one of my roles." Recipe Knowledge The information about recipe knowledge-the knowledge about what should be or should have been done to make things better-was associated both with dictionary knowledge and with directory knowledge. The limited data suggest that two different kinds of recipes existed: recipes of success or failure and recipes for success or failure. The former represented lessons learned from past behavior and strongly recommended continuing to do or avoiding things, such as "improve whenever you see a need for it" or "avoid bottlenecks." This kind of recipe knowledge was associated with directory knowledge in that it was present across the three divisions. Recipes for success or failure suggested changes away from the present state, with mentions such as the desire for a "larger facility," "more pleasant work environment," or mentions of specific problem areas. This kind of recipe knowledge was more closely related to dictionary knowledge in that it was mentioned within the boundaries of a functional domain grouping or division. But, in general, too little information was obtained from the interviews about this kind of knowledge to identify cultural groupings. When I 152/ASO, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures explored potential reasons for the few data obtained about recipe knowledge, the most probable explanation was BIND'S specific dictionary knowledge. The guideline "improve whenever you see a need for it" did not allow much recipe knowledge for success or failure to accumulate. Instead, people made the necessary changes. Although the data are limited, recipes seemed to express more personal than common concerns. These results are therefore the most tentative ones. Subculture Formed around Axiomatic Knowledge Axiomatic knowledge gives insight into why certain things are the way they are in BIND. It is based on basic assumptions that cannot be further reduced. Only one grouping surfaced in regard to this knowledge: the seven members of the top-management group. Lower-level employees acted on this knowledge, but they were not cognizant of it, despite further probing by the researcher. The content of the axiomatic knowledge focused on five assumptions that had been explored and negotiated by the top management during a restructuring phase that had started fourteen years prior to the study. These assumptions were based on the past experiences of the people involved in the planning of the restructuring. The five assumptions concerned the control of BlND and its business environment, ways to ensure long-term success, the nature of the firm's corporate responsibilities, the most appropriate structure for BIND, and the nature of people who work for BlND and who are most likely to succeed in its corporate environment. This axiomatic knowledge defined and framed the slice of reality in which organizational members behaved in their role as BlND employees. DISCUSSION Although this is a study of a single firm, which limits the results' generalizability, it makes several theoretical contributions by shedding light on the complexity of culture in organizations and by indicating some of the parameters for the formation of cultural subgroupings. One reason why the functional domain subgroupings did not surface in regard to directory knowledge may be found in the content of axiomatic knowledge. While people took pride in their work and work-related responsibilities (functional domain groupings), they had been deliberately selected and hired for specific characteristics that were enforced by different structural parameters. The analysis of axiomatic knowledge revealed that axioms about the "right people" and the "right organizational structure" served as preconditions. Since the same preselection and reinforcement conditions existed in the three divisions, they are likely to be responsible for the existence of cultural synergy that existed around directory knowledge. This, in turn, may also explain why only one functional domain grouping formed around axiomatic knowledge. This grouping consisted of people who had actually negotiated the axioms at the beginning of a major restructuring process fourteen years prior to the study. Those who could or did not subscribe to the new axioms left or had to go. Subsequently, people who were hired held 153lASQ. March 1992 personal beliefs in congruence with the negotiated axiomatic knowledge without knowing the axiomatic knowledge base. Axioms are therefore not necessarily dropped out of awareness (Schein, 1985), but one may speculate that they may only become of existential relevance if violated. In regard to recipe knowledge, the few data obtained do not allow me to make any clear statements about the formation of cultural groupings. Recipe knowledge tended to be influenced by personal concerns that could potentially lead to differentiation into other than functional domain groupings. I explored several potential reasons, such as methodological, response, and sampling biases, why little information was obtained here when compared with the other three kinds of cultural knowledge. Probing questions asking about recommendations for what to do or what to avoid did not trigger more information. No systematic response biases were found in a comparison of data from the interviews and participant observations. A critical examination of all data suggested, however, that informants were involuntarily biased due to the particular cultural context of BIND, which does not lead to the accumulation of recipe knowledge. Before recommendations are made or improvement strategies are developed, people act. Based on my working experience with other firms, I would speculate that the presence of a larger amount of recipe knowledge in a firm is linked to problems of internal integration and/or external adaptation. Recipe knowledge may be related to delegating these responsibilities (appropriately or inappropriately) to others. The existence of extensive recipe knowledge could indicate a strong sense of boundaries between "we" who see a need and "those" who have to take care of that need. A study using, for example, a bureaucracy as an organizational research site could lead to better understanding of what kinds of conditions influence the quantity and quality of recipe knowledge. The finding that the same functional domains of different divisions are more similar than different functional domains within the same division further supports previous findings that professional groups (Gregory, 1983) as well as industries (Phillips, 1990) are important influences in the formation of subcultures. They need to be addressed or controlled for in future studies as factors that influence culture in organizations. CONCLUSIONS Given the inductive research approach in this study, the specific findings may serve as hypotheses for studies of culture using deductive research methodologies. First, one may wonder if the proposed framework of cultural knowledge is useful in capturing culture in a particular setting. Its combination with the inductive yet comparative research methodology revealed the co-existence of a homogeneous cultural grouping with different kinds of independent and overlapping cultural subgroupings. The notion of culture as complex and even somewhat paradoxical has been proposed on theoretical grounds (Louis, 1983), without empirical evidence. Existing studies have either focused on predefined subcultures (e.g., Gregory, 1541ASQ. March 1992 Culture and Subcultures 1983; Martin, Sitkin, and Boehm, 1983) or the (homogeneous) culture of a firm (e.g., Schein, 1985). By revealing the simultaneous existence of both, the framework demonstrates its usefulness for a finer-grained analysis of culture. Future application of the framework needs to further investigate the nature of recipe knowledge in different organizational contexts. What would be also of interest is to compare these results with the ones obtained in two other kinds of studies: one that operationalizes and investigates simultaneously, for example, Schein's (1985) values and assumptions and one that uses a purely ethnographic method. Such approaches would help to determine the usefulness of the framework and methodology developed for this study. Second, one may wonder why different cultural subgroupings emerged in regard to the different kinds of cultural knowledge. Hypothetically, one single cultural grouping could have emerged across all four kinds of cultural knowledge, or the functional domain groupings found in regard to dictionary knowledge could have existed consistently across all four kinds of knowledge. The first hypothesis is consistent with the integration paradigm (Martin and Meyerson, 1988) and may be expected in extremely homogeneous settings. It would imply that organizational members identify with the same unit and priorities across functions and hierarchies (dictionary knowledge), that they draw on the same dictionary knowledge for dealing with their tasks, problems, and interactions, that they prescribe the same recipes for action, and that they base their thinking and action on the same stock of axiomatic knowledge. The second hypothesis would imply that the identified subcultures would consistently identify with their group and its accumulated cultural knowledge for priority setting, for processes at work (tasks and interpersonal), for recommendations, and that the different groups would draw on different axiomatic knowledge. These conditions are most likely to exist for groups that operate independently of each other, such as small firms operating autonomously under the umbrella of a holding structure. These considerations indicate that the findings of this study are biased by sampling at the organizational level. In a different organization, different cultural groupings may have emerged, formed possibly through other differentiating processes (Van Maanen and Barley, 1985). Another question of interest is how the cultural grouping according to functional domain differs from differentiation into functions, as suggested in the literature (e.g., Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967; Van Maanen and Barley, 1985). Two differences were observed. First, the influence of functional domain, as found in this study, goes beyond the traditional notion of function to include boundary spanning and temporary groupings (the coordination grouping). Second, the differentiation process observed in this study is primarily based on professional role perceptions and perceived responsibilities rather than on prescribed organizational functions. Both aspects have implications for organizational theory and design. On the one hand, they support an action 155lASO. March 1992 or social constructionist perspective (e.g., Silverman, 1971; Weick, 1979), and, on the other hand, they suggest that the attention given to artifacts such as organization charts or job descriptions may be less helpful in understanding life in a particular organization than a focus on perceived responsibilities. It would therefore be of interest to investigate if a data-collection method centering around perceived work and professional responsibilities would be sufficient to reveal subcultural groupings within an organization. The developed methodology was useful in gaining an understanding of the cultural context of BIND. Furthermore, it was sensitive to subtle subcultural formation processes that a more structured methodology may not have detected. The cognitive bias in studying the essence of culture was not restrictive, since observations of artifacts and behaviors were used to triangulate the interview data. The issue of innovationlchange was appropriate for revealing context-specific or culturally biased information. Since innovation has a predominantly positive connotation, however, future studies could use only the more neutral issue of change. In addition, it would be of interest to compare the obtained results with those of a study using an issue that focuses more on stabilizing rather than adapation or change processes. The study's major contribution is a clearer view of the complexity of culture in organizations. This has not been addressed in prior studies, and some authors have even discarded, on theoretical grounds, the notion of culture as complex and even paradoxical (Schreyogg, 1989). Based on these findings, theoretical arguments about "strong cultures" need to be revised. If a more differentiated cultural perspective is applied, "strong cultures" as described, for example, by Peters and Waterman (1982), could turn out to be less consistent, less strong, and less homogeneous than they appear to be. REFERENCES Argyris, Chris, and Donald Schon 1978 Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Baker, Edwin L. 1980 "Managing organizational culture." Management Review, 69: 8-13. Broms, Henri, and Henrik Gahmberg 1987 Semiotics of Management. Helsinki: Enis-Offset Ky. Brown, Martha A. 1976 "Values-A necessary but neglected ingredient of motivation on the job." Academy of Management Review, 1: 15-23. Davis, Stanley 1984 Managing Corporate Cultures. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger. Deal, Terrence, and Allan Kennedy 1982 Corporate Cultures. Reading. MA: Addison-Wesley. Diesing, Paul 1971 Patterns of Discovery in the Social Sciences. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton. Dutton, Jane, and Robert B. Duncan 1987 "The creation of moment for change through the process of strategic issue diagnosis." Strategic Management Journal, 8: 279-295. Dyer, W. Gibb 1985 "The cycle of cultural evolution in organizations." In R. H. Kilmann, M. J. Saxton, and R. Serpa (eds.), Gaining Control of the Corporate Culture: 20CL229. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Evered, Roger, and Meryl R. Louis 1981 "Alternative perspectives in the organizational sciences: 'Inquiries from the inside' and 'Inquiries from the outside.' " Academy of Management Review, 6: 385-389. Fetterman, David M. 1989 Ethnography: Step by Step. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Goodenough, W.H. 1971 Culture, Language, and Society. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Carney, Thomas 1972 Content Analysis. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. 156/ASQ, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures Gregory, Kathleen L. 1983 "Native-view paradigms: Multiple cultures and culture conflicts in organizations." Administrative Science Quarterly, 9: 259-376. Handy, Charles B. 1978 "Zur Entwicklung der Organisationskultur durch Management Development Methoden" [Developing organizational culture with methods of management development]. Zeitschrift fur Organisation, 7: 404-410. Harrison, Roger 1972 "Understanding your organizational character." Haward Business Review, MayNune: 119-128. Heider, Fritz 1958 The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley. Hofstede, Geert 1980 Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Husserl, Edmund 1975 Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. New York: Collier Books. Ihde, Don 1977 Experimental Phenomenology. New York: Paragon. Jamison, Michael S. 1985 "The joys of gardening: Collectivist and bureaucratic cultures in conflict." Sociological Quarterly, 26: 473-490. Kilmann, Ralph H. 1982 "Getting control of the corporate culture." Managing, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Business, #3. Kroeber, Alfred L., and Clyde K. Kluckhohn 1952 Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Haward University Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology Papers, 47. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum. Lawrence, Paul R., and Jay W. Lorsch 1967 "Differentiation and integration in complex organizations." Administrative Science Quarterly, 12: 1-47. Louis, Meryl R. 1983 "Prerequisites for fruitful research on organization culture." Unpublished manuscript, Center for Applie~ Social Sciences, Boston University. Martin, Joanne, and Deborah Meyerson 1988 "Organizational cultures and the denial, channeling and acknowledgment of ambiguity." In L. R. Pondy, R. J. Boland, Jr., and H. Thomas (eds.), Managing Ambiguity and Change: 93-1 25. New York: Wiley. Martin, Joanne, Sirn Sitkin, and Michael Boehm 1983 "Wild-eyed guys and old salts: The emergence and disappearance of organizational subcultures." Working Paper, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University. Massarik, Fred 1977 "The science of perceiving: Foundations for an empirical phenomenology." Working Paper, Graduate School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles. Miller, George A., Eugene Galanter, and Karl Pribram 1973 Strategien des Handelns, Plane und Strukturen des Verhaltens [Action strategies, plans and structures of behavior]. Stuttgart: Klett. Patton, Michael 0. 1980 Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Peters, Thomas J., and Robert H. Waterrnan 1982 In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best-run Companies. New York: Harper & Row. Phillips, Margaret E. 1984 A conception of culture in organizational settings. Working Paper #%84, Graduate School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles. 1990 "Industry as a cultural grouping." Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Anderson Graduate School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles. Piaget, Jean 1954 The Construction of Reality in the Child. Margaret Cook, trans. New York: Basic Books. 157lASO. March 1992 Sackmann, Sonja A. 1983 "Organisationskultur-die unsichtbare Einflussgrosse" [Organizational cultureThe invisible influence]. Gruppendynamik, 4: 393-406. 1989 "The framers of culture: The conceptual views of anthropology, organization theory, and management." Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Washington, n . I p 1992 "Uncovering culture in organizations." Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences (forthcoming). Sapienza, Alice M. 1985 "Believing is seeing: How organizational culture influences the decisions top managers make." In R. H. Kilmann, M. J. Saxton, and Roy Serpa (eds.), Gaining Control of the Corporate Culture: 66-83. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Sathe, Vijay 1983 "Some action implications of corporate culture." Organizational Dynamics, Autumn: 5 2 3 . Schein, Edgar H. 1985 Organizational Culture and Leadership. A Dynamic View. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 1987 The Clinical Perspective in Fieldwork. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Schreyogg, Georg 1989 "Zu den problematischen Konsequenzen starker Unternehmenskulturen" [The problematic consequences of strong corporate cultures]. zfbf, 41 : 94-1 13. Schutz, Alfred 1962 Collected Papers, vol. 1: The Problem of Reality. Maurice Natanson, ed. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Schutz, Alfred, and Thomas Luckrnann 1975 Strukturen der Lebenswelt [Structures of the daily world]. NeuwiedlDarmstadt. Seiler, Thomas B. 1973 Kognitive Strukturiertheit: Theorien, Analysen, Befunde [Cognitive structuring: Theories, analyses, results]. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. Silverman, David 1971 The Theory of Organizations: A Sociological Framework. New York: Basic Books. Smircich, Linda 1983 "Concepts of culture and organizational analysis." Administrative Science Quarterly, 28: 339-358. Spradley, James P. 1980 Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Tolman, Edward C. 1948 "Cognitive maps in rats and man." Psychological Review, 55: 189-202. Van Maanen, John 1979a "Reclaiming qualitative methods for organizational research." Administrative Science Quarterly, 24: 52CL526. 1979b "The fact of fiction in organizational ethnography." Administrative Science Quarterly, 24: 539-550. White, Leslie A. 1959 "The concept of culture." American Anthropologist, 61 : 227-251. Van Maanen, John, and Steven R. Barley 1985 "Cultural organizations: Fragments of a theory." In L. R. Pondy, P. J. Frost, G. Morgan, and T. C. Dandridge (eds.), Organizational Symbolism: 31-53. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Wilkins, Alan 1983 "The culture audit: A tool for understanding organizations." Organizational Dynamics, Autumn: 24-38. Weick, Karl E. 1979 "The Social Psychology of Organizing, 2d ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. APPENDIX A: Rules for Condensing the Interview Data: InnovationIChange #2 Example Dictionary Knowledge Descriptions of an innovationlchange were marked and listed as dictionary knowledge: Text: "That was number two on my list of things that were innovative . . . incentive plans have been around for a long time, but this one is easily measurable by the employees in the shop. It allows them to make a lot of money if they produce good parts fast . . ."[a more detailed description of this plan continues]. Condensed as: Incentive plans that are easily measurable by employees. Inferences: [Process innovationlpeople orientation]. Directory Knowledge Four different kinds of information were listed as directory knowledge. These were (1) originlcontext of the particular innovationlchange, (2) how it had come about, (3) who was involved, and (4) where it had occurred. Only one example is given for each category: Text: ". . . which the PC division always had since 1960. . . . It was not started by me. It was started by Ben. . . ." Originlcontext: Current presidentlthen-general-manager initiated it. (In 1960, PC was owned and managed by the current president.) Text: ". . . [in production] engineering establishes the numbers . . . they prepare an estimate sheet and that's how we develop our standards [people cocerned]. Those estimates that are established go as standards into the shopfloor. The first time around they are less accurate than they are the second and the third time around, because the first time is our best guess [constant improvement]. But then we have historical data after that. So when an employee picks up his route sheet and he sees 10 hours, 100 pieces and he beats that, great [people orientation]. . . . When we close out a job, which is done 30 days after the last shipment-the reason we allow 30 days is for any customer returns, we give our customers 30 days to inspect the parts [relationships with people]-then we do a closed job report . . . [detailed description how this is done]. . . . For the employee we sort out by employee and then every job that the employee worked on every operation inside of each job whether or not they are ahead or behind standards [controll. So they get a printout that goes right along with their paycheck on the weeks that they receive bonus and it says 'Here's the job you worked on, here's how many hours you earned, here is how much rework you caused, here is how much rework is subtracted from your bonus,' and then on their paycheck we 158lASQ, March 1992 Culture and Subcultures recalculate their new hourly rate . . . " [work efficiently while maintaining quality]. How? 1. Introduced from the top; adjustments [constant improvements]. 2. People concerned were involved. 3. Control system was developed so that its correct use is rewarded [people orientationlcontroll. 4. People profit from it [people orientation]. 5. Work efficiently while maintaining quality. Who? One general manager started it. Where? Plan started in one manufacturing facility. Recipe Knowledge Recommendations or prescriptions were listed as recipe knowledge: Text: ". . . [at the PC division w e had] excellent experience [with the incentivelbonus plan] [controlled experimentationlconstant improvement]. And w e installed it 1% years ago at the PMC division and their profit has more than doubled in 12 months. . . . We are now trying to install that at the CM division. . . . So hopefully at the end of this year we are able to turn on an incentive bonus plan. . . . What w e are trying to do now is get into all nine locations that do some or all manufacturing. We got now two on it [incentive plan] . . . and we are getting number three and four hopefully this summer" [controlled experimentation]. Condensed as: Try something new in one location; implement it in other locations successively if it works and adaptlimprove it in the process. Inferences: [Controlled experimentationlconstant improvementldon't upset the entire company at once]. Axiomatic Knowledge Axioms (basic underlying premises) were tentatively marked, further probed in the interviews, and later listed as axiomatic knowledge: Text: " . . . that part I think is happening with every good employee we have. That's instilled, that's like part of cheerleaders. . . . I think 90 percent is what you are born with, 20 percent is developed. It's just something that's in your nature, . . . maybe not born but by the time you are two or three years old, it's just an attitude that you have. You know, we have employees that come in who are extremely bright but they don't have that attitude. . . . When I interview people, I look for those particular traits to see how they respond to particular questions rather than talk a lot. . . . Usually within the first five or six minutes you get a real reading . . . what their attitude is as a person . . . so usually it clicks or it doesn't click. . . . Our particular type of person, we need to have people who are self-motivated, you know, initiators, w e need to have people that are profit oriented, w e need to have people that are communicators, people oriented, people that are willing to take responsibility. . . ." Inferences: [The nature of people working for BINDlpre-selection]. APPENDIX B: Examples of a Condensed Content Analysis Listed are condensed quotes from the interviews. To avoid duplication, condensed content analyses are given here only for InnovationslChanges #1 and #3: InnovationIChange #2 is the example in Appendix A. The "General Themes" section, below, however, covers all three innovationslchanges. The italicized material contains themes at the group level of analysis. The numbers indicate the level of generalization, where 1 represents the highest level of generalization and 3 the lowest level of generalization or the most specific one. INNOVATIONICHANGE #1 Dictionary Technological innovation in terms of sales, profit generation, and creativity that turns into a process innovation: manufacturing of substrates for 159lASQ, March 1992 computer disk drives in larger quantities at increasingly smaller tolerances [build successful company (1,Z)lstrategy (I)]. Directory Originlcontext: Response to outside demand [need-basedaction]. How? 1. BlND was approached to build substrate [customizedR&D]. 2. BlND designed and built equipment to reach high tolerances of accuracy [controlled experimentationl. 3. First, a prototype is developed to see if it can be built; if positive, the contract is accepted [controlled experimentation). 4. Second, large-scale production with high accuracy [growth orientation]. 5. Third, constant upgrading and improvement of old machinery; building new equipment [constant improvement]. 6. "Diversification": manufacturing of different sizes [building on strengthslcontrolledexperimentationl. 7. Plant expansion [growth orientation]. Who? Engineers, toolmakers, machinists-everybody. Where? 1. Where expertise is located, plus cooperation and teamwork among people involved [individual contributionlteamwork]. 2. Later, equipment is moved to Oregon plant; they have technical expertise there and a good labor market [cost and quality orientation]. Recipe 1. Be and stay an expert in your field [constant improvement]. 2. Use expertise of others [teamwork]. 3. Improve constantly; respond to customer needs [strategy]. 4. Be more pervasive to accomplish tasks faster. 5. Good management means two-way communication, responsiveness to employees' needs, competitive benefits and wages. INNOVATIONICHANGE #3 Dictionary In-house computer system; could be innovative once it is installed in all divisions (not yet accomplished) [structure (2)lprocess innovationlcontrolled experimentation and diffusion). Directory Originlcontext: Initiated by internal and external needldemand [need-based improvement]. 1. Internally: old system was not powerful enough. 2. Externally: some good product-line vendors only do business with one location instead of several. 3. BIND'S computer system should be compatible with the one of their major product-line vendors [strategy]. How? 1. Engaged several knowledgeable people in research [use expertiselindividual contribution]. 2. Frequent discussions of information and joint evaluation of different options [teamworkllearning orientation]. 3. Implementation process: a three-month pretraining of key people, then six-month supervision and assistance through support group [controlled experimentationlpeople orientationlshift responsibilities downlcontrol orientationlconstant improvement]. Who? Special task group. Where? In the corporate office and in data processing. Recipe 1. Get people involved and prepare them. 2. Persuade people: show advantages; don't force them to do things beople orientationlindividual contributionlshift responsibilities down]. 3. Control, follow-up, and adapt [control orientationlconstant improvement]. 4. Watch closely to improve [constant improvement]. 160lASQ. March 1992 Culture and Subcultures General Themes, Assumptions, Concerns/Emphasis, Attitudes: Comparisons across Innovations/Changes Dictionary 1. Innovation is something radically new that has not existed before and that works. 2. Considers the three innovations as borderline situations. 3. As the i n t e ~ i e wwent on, he started to question his own definition of innovation as radically new. Directory 1. Try to think of ways to save money. 2. Try to eliminate anything that is a problem. 3. Accept people and opportunities as they are and make the best use of them. Recipe 1. BlND needs more future planning; not just six months ahead. 2. Respect the preciousness of time. 3. Be more persuasive so that things happen faster. 4. Get qualified people. Problem: BlND will become more centralized in certain functions-makes it harder to attract "good" people for divisions [good = take initiative and responsibilitieslintrapreneurs]. 5. He would like to have more people think the way he does. Concerns/Emphasis 1. Controlled profitable growth. 2. Work efficiency. 3. Try to save money. 4. Eliminate any problems ("bottlenecks"). 5. Need people with "right" attitude: these are self-motivated, willing to take responsibility, communicators, people-oriented, entrepreneurs-they want to save money and work more efficiently. 6. Provide opportunities for people and let them use their skills, talents. 7. Attract and retain initiators rather than maintainers. 8. Things can always be improved. 9. Business philosophy determines structure. 10. The best organization ultimately depends on market demands [centralized vs. decentralized-he prefers to be decentralized. Attitudes toward Employees: 1. Partnership: We are in this thing together. 2. They need attitude to do things more efficiently. 3. Need "right" people; it "clicks" or it doesn't; self-motivated, willing to take responsibilities, experts in their field. Being a businessman: 1. The work of a businessman is art: you need to do everything simultaneously to achieve controlled profitable growth. 161/ASQ, March 1992 http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 1 of 2 - You have printed the following article: Culture and Subcultures: An Analysis of Organizational Knowledge Sonja A. Sackmann Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 1. (Mar., 1992), pp. 140-161. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28199203%2937%3A1%3C140%3ACASAAO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 This article references the following linked citations. If you are trying to access articles from an off-campus location, you may be required to first logon via your library web site to access JSTOR. Please visit your library's website or contact a librarian to learn about options for remote access to JSTOR. References Values - A Necessary but Neglected Ingredient of Motivation on the Job Martha A. Brown The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 1, No. 4. (Oct., 1976), pp. 15-23. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0363-7425%28197610%291%3A4%3C15%3AV-ANBN%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Y The Creation of Momentum for Change Through the Process of Strategic Issue Diagnosis Jane E. Dutton; Robert B. Duncan Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 8, No. 3. (May - Jun., 1987), pp. 279-295. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0143-2095%28198705%2F06%298%3A3%3C279%3ATCOMFC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L Alternative Perspectives in the Organizational Sciences: "Inquiry from the inside" and "Inquiry from the outside" Roger Evered; Meryl Reis Louis The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 3. (Jul., 1981), pp. 385-395. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0363-7425%28198107%296%3A3%3C385%3AAPITOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W Native-View Paradigms: Multiple Cultures and Culture Conflicts in Organizations Kathleen L. Gregory Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3, Organizational Culture. (Sep., 1983), pp. 359-376. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28198309%2928%3A3%3C359%3ANPMCAC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-M http://www.jstor.org LINKED CITATIONS - Page 2 of 2 - Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations Paul R. Lawrence; Jay W. Lorsch Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Jun., 1967), pp. 1-47. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28196706%2912%3A1%3C1%3ADAIICO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis Linda Smircich Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3, Organizational Culture. (Sep., 1983), pp. 339-358. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28198309%2928%3A3%3C339%3ACOCAOA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-D Reclaiming Qualitative Methods for Organizational Research: A Preface John Van Maanen Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4, Qualitative Methodology. (Dec., 1979), pp. 520-526. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28197912%2924%3A4%3C520%3ARQMFOR%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6 The Fact of Fiction in Organizational Ethnography John Van Maanen Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4, Qualitative Methodology. (Dec., 1979), pp. 539-550. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0001-8392%28197912%2924%3A4%3C539%3ATFOFIO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-1 The Concept of Culture Leslie A. White American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 61, No. 2. (Apr., 1959), pp. 227-251. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-7294%28195904%292%3A61%3A2%3C227%3ATCOC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R