to - Australian Heritage

advertisement

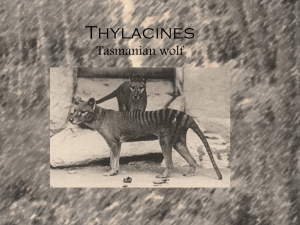

Tyger, tyger, burnt out The demise of the thylacine The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, has acquired almost mythical status since it was hunted to extinction last century. Once widespread across Tasmania, the Australian continent and New Guinea, the thylacine seems to have been quite susceptible to changes in its habitat, and its fate was sealed when European settlers decided that it posed an unacceptable threat to their sheep. BY MARK KELLETT T ALES OF STRANGE carnivorous beasts lurking in the forests of Van Diemen’s Land had been told since the visit of the Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman, in 1642. His pilot-major, Francoys Jacobz, had led a shore party on the 2nd of December and described finding “the footing of wild beasts having claws like a tiger”. However, his report, as with many others of strange tracks and halfglimpsed animals that followed it, is so vague that modern readers cannot be certain what animal is being described (wombats, for example, have such long claws). On the 21st of April, 1805, the Sydney Gazette printed a report of a strange animal found near the shortlived settlement at Yorktown on Port Dalrymple in the north of the island. An animal of a truly singular and novel description was killed by dogs on the 30th of March on a hill immediately contiguous to the settlement. From the following minute description of which, by Lieutenant Governor PATERSON, it must be considered of a species perfectly distinct from any of the animal creation hitherto known, and certainly the only powerful and terrific of the carnivorous and voracious tribe yet discovered on any part of New Holland or its adjacent islands. Paterson’s detailed description is the first indisputable account of an animal PICTURE ABOVE: Male and female of the Thylacinus cynocephalus. (1841), H. C. Richter. From Mammals of Australia by John Gould (1804–1881). Even at this early date, Gould was pessimistic about the thylacine’s survival. National Library of Australia, nla.pic-vn3292764. Australian Heritage 73 that was to become despised by, and later emblematic of the people of the island. It is very evident that this species is destructive, and lives entirely on animal food; as on dissection his stomach was found filled with a quantity of kangaroo, weighing 5lbs, the weight of the whole animal 45lbs. From its interior structure it must be a brute peculiarly quick of digestion; the dimensions were, ... length of the eye, which is remarkably large and black, 13/4 inches; ... length of the tail, 1 foot 8 inches; length of the fore leg 11 inches; and of the fore foot, 5 inches; the fore foot with 5 blunt claws; ... stripes across the back 20, on the tail 3; 2 of the stripes extend down each thigh; length of the hind leg from the heel to the thigh, 1 foot; length of hind foot, 6 inches; the hind foot with 4 blunt claws, the soles of the feet without hair; ... 8 fore teeth in the upper jaw, and 6 in the under; 4 grinders of a side, in the upper and lower jaw; 3 single teeth also in each; 4 tusks, or canine teeth, length of each 1 inch; ... the body short hair and smooth, of a greyish colour, the stripes black; the hair on the neck is rather longer than that on the body; the hair on the ears of a light brown colour, on the inside rather long. The form of the animal is that of a hyaena, at the same time strongly reminding the observer of the appearance of a low wolf dog. Van Diemen’s Land’s first SurveyorGeneral, George Harris, officially described the animal in 1806 on the basis of two male specimens that had been caught with traps baited with kangaroo-meat. Placing it in the same genus as the American opossums, he gave it the scientific name of Didelphis cynocephala (dog-headed opossum). The creature he described would come to be known by an astonishing range of common names, almost all of them misleading as to its affinities: legunta, dog-faced dasyurus, hyena opossum, zebra opossum, Tasmanian dingo, pouched wolf, striped wolf, Tasmanian wolf, zebra wolf, and Tasmanian tiger. In 1824 another naturalist, Coenraad Temminck, recognised the animal as distinct from the American marsupials and gave its 74 Australian Heritage modern name: Thylacinus cynocephalus (pouched and dog-headed), and hence thylacine, the common name now most often used. The thylacine superficially resembled a German shepherd dog in size and shape. However, while dogs are placental mammals, thylacines were marsupials related to the Tasmanian devil, giving birth to up to four young at an early stage of development and rearing them in a backward-facing pouch. In a process called convergent evolution, the similar way of life adopted by the ancestors of thylacines and dogs led to their descendants developing a similar form. of Austral-Asia of 1839, “...in running it bounds like a kangaroo, though not with such speed.” The thylacine may have attempted to catch its prey in an ambush, but if that failed, it would patiently trot after its prey. Its persistence was notable, as a miner named Oscar described in the Mercury in 1882: “This native tiger is not swift, and is very awkward in turning, but it follows the trail by its never-erring scent, and in the long run is sure of its prey.” When the thylacine caught up with its prey, usually small kangaroos, wallabies, possums, sometimes native rodents, bandicoots, birds, lizards and even echidnas, its jaws and teeth were put to work. Its jaw had the largest gape of any land mammal and could close with great force, as the hunter Hugh Mackay related: A bull-terrier once set upon a wolf and bailed it up in a niche in some rocks. There the wolf stood, with its back to the wall, turning its head from side to side, checking the terrier as it tried to butt in from alternate and opposite directions. Finally the dog came in close and the wolf gave one sharp, fox-like bite, tearing a piece of the dog’s skull clean off and it fell with its brain protruding, dead. Zebra, or dog-faced dasyurus. Didelphis cynocephala. Harris, James Basire, Georges Cuvier, State Library of Tasmania. Clearly the artist had not seen the living animal. There were other important differences between dogs and thylacines. Thylacines had a rather stiffer spine and tail, shorter legs, and feet that were held flatter to the ground than dogs of similar size. This combination of features gave it a different gait, endowing the animal with endurance at the expense of speed. Certainly dogs seem to have easily caught up with them. Perhaps misled by the fact that the thylacine’s front legs are rather shorter than the rear, R M Martin noted in his History Like other carnivorous marsupials, its fangs were oval and suited for crushing, while the molars were somewhat primitive and shaped for cutting (dogs, by contrast, have slashing canines and a mixture of slicing and crushing molars). Thylacine teeth are almost unworn, supporting records of the marsupial delicately picking out the most nutritious parts of its prey: the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and if it was really famished, the muscle from the inner thighs, leaving the rest for scavengers like Tasmanian devils. This fussy diet may have led to the wholly erroneous belief that the thylacine fed on blood, first recorded by British scientist Geoffrey Smith in 1909. This myth doubtless helped to make the animal an object of hatred and fear. Though it is difficult to reconstruct the behaviour of an extinct animal, some of the most striking differences A rare photograph of one of the last thylacines held in captivity. Like ‘Benjamin’, who was possibly the last member of the species, its end was probably a lonely one. between thylacines and dogs might have been behavioural. It is now known that many marsupials have a brain two-thirds the size of placental mammal of similar size and habit, and thylacines were no exception to this. This may have been the result of a simpler social structure, thylacines hunted alone or perhaps as a mated pair or as a mother with joeys, while dogs form much larger packs. With less need to communicate, thylacines do not seem to have vocalised much, communicating among themselves with a muted coughing bark and giving a hissing growl when antagonised. Ultimately, the thylacines smaller brain and simpler behaviour may have reduced its capacity to adapt to the changes that overtook it. The thylacine was the last survivor of a once successful family. Twelve fossil members of the thylacine family are described in a recent paper by Stephen Wroe, ranging from fox-sized to wolf-sized predators, most of which lived between 20 million and 8 million years ago in different parts of Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea. Over this period, there seem to have been between four or five thylacine species living at any given time. By the time the first Aboriginal people arrived some 60,000 years ago, their fortunes had waned and only the modern thylacine remained. Thylacines became extinct in New Guinea about 10,000 years ago and in mainland Australia about 3,000 years ago. Although the causes of these extinctions are not known, the disappearance of the thylacine in Australia coincided with the arrival of the first dingos (Canis familiaris). It has been suggested that the dingo may have competed catastrophically with the mainland thylacine for food and living space. Though there are suggestions that small relic thylacine populations may have persisted on the mainland, only in Tasmania, isolated from the mainland by Bass Strait about 12,000 years ago, did it survive to be seen by Europeans with certainty. This isolation ended abruptly in 1803 when the British colonised Van Diemen’s Land in a move to thwart any territorial ambitions of the French. A year later Hobart Town (later Hobart) and Patersonia (later Launceston) were founded. Two animals that came in the company of the settlers were to prove deadly for the thylacine. In the chaotic conditions of the early settlements, some domestic dogs escaped and formed feral packs. It is possible that such wild dogs attacked thylacine; domestic dogs have been described as being either terrified or enraged by them. Dogs also would have competed with thylacines for the kangaroos and wallabies that made up the bulk of its diet. Ultimately, the worst effect of feral dogs on the thylacine would turn out to be an indirect one. In the early Tasmanian settlements, sheep were primarily a food supply for the colonists, though small numbers of wool-producing sheep were on the island as early as 1806. With the mainland settlements making fortunes from wool, significant numbers of merino sheep began to arrive in Van Diemen’s Land after 1820. There were some losses among these early flocks and. although it does not seem unreasonable that thylacines might have been responsible for some of them, reports of spree-kills of sheep seem more likely to have been the work of dogs. However, a series of mistaken human acts ensured that the thylacine would take the blame. By 1819, the Van Diemen’s Land flocks were more than twice the size of those of the New South Wales colonies. Anxious to maintain investment in the mainland colony, W C Wentworth wrote about a wholly imaginary “animal of the panther tribe” that “...commits dreadful havoc among the flocks.”. Unfortunately, this was misconstrued as a description of the thylacine, and three years later the Surveyor General, George William Evans, paraphrased Wentworth’s description in the Description of Van Diemen’s Land. In 1826 the Van Diemen’s Land Company was granted extensive Australian Heritage 75 A more accurate portrayal of the thylacine from The Mammals of Australia,1869, Harriet Scott, Thomas Richards, Victor A Prout, Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts. holdings in the north-west of the island to farm sheep. However, the land was poorly selected and the sheep died of exposure or starvation, or were taken by predators, human and animal, imported and indigenous. Ignoring the more serious difficulties, the company’s directors seized on the wild predators as a problem they could solve. In 1830 the company offered five shillings for male thylacines and seven for females, with half these amounts for Tasmanian devils and feral dogs, an odd choice, considering that the company’s records indicate that dogs were responsible for most kills. The company offered rewards for thylacines on and off until into the next century, and other graziers followed its example. It seems that this bounty-hunting may have only reduced thylacine numbers near inhabited areas, but did set a precedent for how the animal was to be dealt with. Prophetically, the great naturalist, John Gould, suggested in his classic Mammals of Australia that the thylacine might not be able to withstand such persecution indefinitely: 76 Australian Heritage When the comparatively small island of Tasmania becomes more densely populated, and its primitive forests are intersected from the eastern to the western coast, the numbers of this singular animal will speedily diminish, extermination will have its full sway, and it will then, like the Wolf in England and Scotland, be recorded as an animal of the past: although this will be a source of much regret, neither the shepherd nor the farmer can be blamed for wishing to rid the island of so troublesome a creature. Through the 1880s, the wool industry was in crisis, and the colonial government was under pressure to help the industry. Although a crash in the price of wool, drought, disease, rabbit plagues and wild dogs were the main problems, wealthy farmers’ lobby groups like the Buckland and Spring Bay Tiger and Eagle Extermination Association, the Glamorgan Stock Protection Association, the OatlandsRoss Landowners Association and the Midlands Stock Protection Association agitated for the government to take action against the thylacine. They found their voice in the ambitious Tasmanian House of Assembly member for Glamorgan, John ‘Tiger’ Lyne. In 1886, after citing the inflated figure of “...30,000 or 40,000 sheep were killed annually by dingoes”, and arguing that since the thylacines were breeding on crown land the onus was on the government to control them, he proposed £500 be set aside each year for the destruction of the thylacine, with £1 paid for each adult thylacine killed and 10 shillings for each pup. In the face of dissent about the cost of the proposal, the bill was deadlocked. It was only passed with the vote of the Speaker of the House, Alfred Dobson, an action against custom whereby the Speaker is expected to vote against such a deadlocked bill. The first bounty was paid in 1888. Deafness forced Lyne to retire from politics in 1893, but 2184 thylacines were to be killed as a consequence of his attempt to seek the vote of the woolly aristocracy. The task of hunting the thylacine fell to ‘tiger men’. The animal’s shy, solitary and nocturnal nature made it difficult to hunt. Some trapped the marsupial with a snare left in a hole in a fence or on a forest game trail. Others used dogs to track and corner the thylacine. Tiger men returning from a hunt took the carcasses to the local police station, where the ears and toes were clipped to show that a bounty had been paid. Farmers would sometimes pay an equivalent bounty for a thylacine carcass. The carcass itself seems to have been considered useless. It has often been said that thousands of waistcoats were made of the animal’s pelts, but this seems to be apocryphal; certainly no such garment is known to exist now. A few thylacine-skin rugs were made, and a rather ghoulish individual made a pincushion with a thylacine skull. Not everyone applauded the slaughter. Like most carnivores, adult thylacines were wary of man, but joeys taken young enough could be readily tamed and trained. In 1842 the botanist Ronald Gunn described his experience of raising and taming three thylacine joeys in the Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Van Diemen’s Land. He was a rare voice of support for the thylacine, asserting “It seems far from being a vicious animal at its worst, and the name Tiger or Hyaena gives a most unjust idea of its fierceness.” Zoos had also acted to improve the thylacine’s reputation. They were kept locally in Hobart and Launceston, on the mainland in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide and as far away as Britain, Germany, Austro-Hungary, America, India and South Africa. They were not regarded as very glamorous creatures; like most carnivores in captivity they were rather smelly, and forcing the animal to be active during the day made them lethargic and stressed. Zoos made no direct contribution to the conservation of the thylacine, as they were not kept in such a way as to encourage breeding in captivity, but they did act to shift public opinion away from the belief that the animal was a blood-drinking monster. There were tentative calls for its destruction to be curbed. By this time the animal was in need of such protection. Each year the bounty was in effect, the government was paying for 100 or so thylacines. This number halved in 1906 and, when the bounty was withdrawn in 1909, only two bounties had been paid. Prices offered by zoos, between £7 and £8, had something to do with this. But it was also clear that the thylacine had undergone an islandwide population crash. Its exact cause is not known, though contemporary reports of thylacines suffering from a debilitating disease must be considered a possible cause. After the Great War it was apparent the thylacine was very rare. Prices offered by zoos rose again and again, London zoo paying £150 for one in 1926. Scientists and naturalists like Thomas Flynn, Professor of Zoology at the University of Tasmania, and Clive Lord, director of the Tasmanian Museum, patiently fought through a political smokescreen that the thylacine was in no danger and a bureaucratic minefield to have the thylacine protected. In 1930 they succeeded in getting a ban on hunting thylacines during their breeding season in December and on the international traffic in live animals. Yet it was still shot for sport or as a pest. In the same year a farmer from Mawbanna named Wilf Batty, incensed by an adult female thylacine’s spree in a chicken coop, became the last man indisputably to have shot a wild thylacine. Surprisingly, there is controversy about the identity of the last thylacine in captivity. The female could either have been sold to the zoo as a joey by Walter Mullins in 1924 along with her mother and two littermates, or as an adult in 1933 by Elias Churchill. It is possible that both are true, that when the older thylacine died she was discreetly replaced with the younger one, as a parent may replace a child’s beloved budgie to avoid a fuss. In 1933 she was visited by David Fleay, who had unsuccessfully applied for the position of Director of the Tasmanian Museum. While in the Native Tiger of Tasmania shot by Weaver 1869 (Thylacine), 1869. One of the few photographs of a thylacine from the 19th century. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Australian Heritage 77 Thylacine: Wilf Batty with animal shot at Mawbanna, 1931. the terrified reaction of the dog to Batty’s kill. vicinity, he gained the zoo’s permission to enter the animal’s enclosure and film it. While Fleay was arranging the camera, the thylacine crept around and bit him on the backside. Fleay was more amused than angry, and carried the scar proudly for the rest of his days. This incident produced just over a minute of silent, black and white footage that is the only film record of the thylacine. The last thylacine in captivity died, alone and neglected, on the 7th of September, 1936. Ironically, she had spent the last two months of her life as what seems to have been the sole representative of a completely protected species. Even more ironically, as the result of an apparent scam by a Geelong resident named Frank Darby, she has come to be known as Benjamin. It took some time for people to realise that the thylacine had become extinct. Books written as late as the 1970s either describe the thylacine as a living animal or as “possibly extinct”. Expeditions were sent out over the twentieth century, among them one led by Fleay in 1945, with their objective gradually changing from capturing one for a zoo to proving the continued existence of the species. However, none of them yielded anything other than brief, unverifiable sightings and smudged prints. 78 Australian Heritage Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Note Proving an animal is extinct, like proving any negative, is difficult. A rule of thumb commonly accepted among biologists is that if there has been no indisputable evidence of an organism for 50 years, the animal is considered extinct. Although there is a background noise of sightings in Tasmania and even a few on the mainland and New Guinea, none are accompanied by indisputable evidence. When even a recent $1.2 million reward offered by the Bulletin magazine cannot produce such evidence, it appears the animal is indeed extinct. Ironically, the people whose ancestors harried the thylacine out of existence have adopted it as a mascot. A pair of thylacines flanks the Tasmanian coat of arms and anyone who wishes to show their pride in their Tasmanian heritage, from the environmentalist lobby to big business, places one on their banner. It is a pity the animal could not have gained such status while it was alive, though perhaps it could only adopt such a cuddly image by being safely dead. In 1999 a team based in the Australian Museum led by Michael Archer sought to reverse this situation. They hoped to isolate DNA from a thylacine joey preserved in spirits in 1866, with the ultimate aim of cloning the animal and regenerating the species. Although the team was able to succeed in its first goal, and even got as far as determining the sequence of three thylacine genes, in 2005 it was realised that genetic technology is simply not advanced enough to achieve Archer’s very ambitious objective. What is known about the thylacine has been reconstructed from examination of dead specimens and from a motley assembly of the recollections of people who claimed to know it, most of whom are now dead. Though this approach is useful, it leaves many questions unresolved. When the biology and ecology of the animal itself are disputed, the forces that pushed it to extinction must be similarly unclear. How important was hunting? How important was landclearing? How important were dogs; and if so, was it directly, by hunting, or indirectly through competition for food sources? What role, if any, did disease play? Any change in the relative importance of these factors ultimately alters the answer posed by modern scientists and naturalists: could the thylacine have been saved? Since their predecessors could not even determine whether the marsupial should have been saved, the question will remain unanswered. The Author Dr Mark Kellett is a biologist and a freelance science writer. Further Reading Thylacine by David Owen, Allen & Unwin, 2003. The Last Tasmanian Tiger by Robert Paddle, Cambridge University Press, 2000. Australian Marsupial Carnivores: Recent Advances in Palaeontology by Stephen Wroe, in Predators with Pouches: the Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials, edited by Menna Jones, Chris Dickman & Mike Archer, CSIRO Publishing, 2003. Mammals of Australia by John Gould, annotated by Joan M Dixon, Macmillan, 1983. Furred Animals of Australia by Ellis Troughton, Angus and Robinson, 1946. The Doomsday Book of Animals by David Day, Ebury Press, 1981. Extinct by Anton Gill and Alex West, Channel 4 Books, 2001 (the television documentary series is also very useful). The Thylacine Museum website: www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine ◆