Trinity County Gold Mining History: 1848-1962

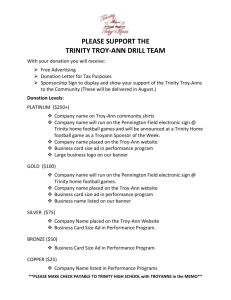

advertisement