Mozart 39 - St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

advertisement

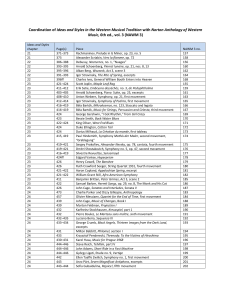

CONCERT PROGRAM February 21-23, 2014 Bernard Labadie, conductor Philip Ross, oboe Andrew Gott, bassoon Kristin Ahlstrom, violin Melissa Brooks, cello RAMEAU Les Boréades Suite (c. 1763) (1683-1764) Rigaudon Menuets Entrée Gavottes pour les heures Air vif Air andante Pas de deux Contredanses HAYDN Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, Hob. I:105 (1792) (1732-1809) Allegro Andante Allegro con spirito Philip Ross, oboe Andrew Gott, bassoon Kristin Ahlstrom, violin Melissa Brooks, cello INTERMISSION HAYDN Symphony No. 22 in E-flat major, “The Philosopher” (1764) Adagio Presto Menuetto Finale: Presto MOZART Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, K. 543 (1788) (1756-1791) Adagio; Allegro Andante con moto Menuetto: Allegretto Finale: Allegro 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bernard Labadie is the Daniel, Mary, and Francis O’Keefe Guest Artist. Philip Ross is the Helen E. Nash, M.D. Guest Artist. The concert of Friday, February 21, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Orrin Sage Wightman III. The concert of Friday, February 21, includes coffee and doughnuts provided by Krispy Kreme. The concert of Saturday, February 22, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield. The concert of Sunday, February 23, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mrs. Mariam Sisson. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. These concerts are presented by the Thomas A. Kooyumjian Family Foundation. These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors series. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Dielmann Sotheby’s and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 FROM THE STAGE Eva Kozma, Assistant Principal Second Violin, on Mozart’s Symphony No. 39: “I love the last movement because of its energy. We play our hearts out. “This is one of the last symphonies of Mozart, and at times it is very serious. It’s dramatic. You’re constantly looking for the Mozartean lightness, the happiness, but the chords are diminished. “Whenever I play Mozart I think of my grandmother. She loved Mozart. She was concertmaster in my hometown orchestra in Romania, and she once said in a radio interview that Mozart made the most genial music ever written, pure and beautiful. I think so too.” Dilip Vishwanat A view of the second violins, Eva Kozma at far right. 25 VARIED INVENTION BY PA U L SC H I AVO TIMELINKS 1763-64 RAMEAU Les Boréades Suite HAYDN Symphony No. 22 in E-flat major, “The Philosopher” Britain, Spain, and France sign Treaty of Paris, ending “Seven-Year” War or “French-Indian” War, with France relinquishing territories in the New World 1788-92 MOZART Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, K. 543 HAYDN Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, Hob. I:105 French Revolution erupts, Declaration of Rights of Man issued The four compositions that comprise the program for our concert were written by three composers within the space of barely 30 years, a relatively short span of time in historical terms. This and the fact that two of these composers were close friends and influenced by each other’s work might promise a certain stylistic homogeneity. But quite the opposite is true. Each of these works is quite distinct in sound, form, and character. We begin with a suite of dances in the French Baroque manner, a style that was out of date in 1763, when this music was composed, but kept alive through the remarkable longevity of its author, Jean-Philippe Rameau. Next comes a concerto, but with the unusual feature of using not one but four solo instruments. Following intermission we hear symphonies by Joseph Haydn and his friend Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The latter work presents what we have come to think of as the classical symphonic design, with fast opening and closing movements framing a slow movement and minuet. But Haydn’s “Philosopher” Symphony follows a different and quite unusual course, opening with a dignified slow movement marked by contrapuntal textures, and using unusual instrumental colors throughout. Together, these four pieces indicate something of the variety of compositional invention that marked the last third of the 18th century, an exceptionally fertile period in the history of Western music. 26 JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Les Boréades Suite A LONG AND VARIED CAREER Jean-Philippe Rameau was, by any measure, one of the most remarkable composers of the Baroque era. Born in France but trained in Italy, he spent his early years as an organist and composer of sacred music and keyboard pieces. By 1723 he had moved to Paris, where he held no regular position but seems to have earned his living as a freelance musician and writer. (Among other things, he authored several famous treatises on music theory.) At age 50, Rameau embarked on a new career as a composer for the theater. His opera Hippolyte et Aricie, which premiered in 1733, created a sensation in Paris, due to the unprecedented dramatic power of its music, and the composer found himself at the center of a critical storm, with rival factions alternately praising and condemning the intensity of his style. Undaunted by this controversy, Rameau wrote a new opera in nearly each of his remaining 30 years. Our concert begins with selections from Rameau’s last opera, Les Boréades. A great deal of uncertainty surrounds the history of this piece. The work was commissioned by the Paris Opéra, which put it into rehearsal in 1763, the year before Rameau died. But there is no evidence that it was actually performed. Concert presentations of excerpts from the score occurred in the 1890s and again in the 1960s in France, but the first staged production, at least the first that anyone knows of, was not given until 1982. STORY AND SPECTACLE The tale related in Les Boréades centers on Queen Alphise of Bactria, an ancient kingdom in the Near East, who spurns the Boreas, god of the wind, in favor of a young mortal she loves. Angered by this affront, the god raises a mighty gust that carries off the disobedient queen. But in a classic deus ex machina reversal, Apollo intervenes and declares that Alphise’s beloved is actually his offspring and a distant descendant of Boreas also, so all ends well. Les Boréades fulfills the traditional requirement of French Baroque opera for an extensive use of dance, either to advance the plot or 27 Baptized September 25, 1683, Dijon Died September 12, 1764, Paris First Performance Unknown (see below) STL Symphony Premiere This week Scoring 2 flutes 2 piccolos 2 oboes 2 clarinets 2 bassoons 2 horns strings Performance Time approximately 15 minutes Born March 31, 1732, Rohrau, Austria Died May 31, 1809, Vienna First Performance March 9, 1792, in London, under the composer’s direction STL Symphony Premiere January 23, 1953, with Leonard Arner, oboe, Norman Herzberg, bassoon, Harry Farbman, violin, and Dodia Feldin, cello, Eleazar De Carvalho conducting Most Recent STL Symphony Performance November 2, 2008, with Barbara Orland, oboe, Andrew Gott, bassoon, Alison Harney, violin, and Melissa Brooks, cello, Nicholas McGegan conducting Scoring solo oboe solo bassoon solo violin solo cello flute 2 oboes bassoons 2 horns 2 trumpets timpani strings Performance Time approximately 22 minutes simply as picturesque diversion. Rameau’s score is filled with gavottes, minuets, rigaudons and other dances popular with the French aristocracy during the 18th century. These numbers would have been occasions for lavish stage spectacles during Rameau’s day, sumptuously choreographed and costumed tableaux of the kind that long typified opera in Paris. Our suite includes a selection of the dance movements Rameau composed for Les Boréades. Most of these require no comment. But the “Gavotte pour les heures” has unusual dramatic significance. Late in the opera, the bereft Arabis is cheered by the arrival of Polyhymnia, the muse of prayers and hymns. With her is a company of allegorical figures representing the seasons, zephyrs, and hours. The latter engage in a dance that inspired Rameau to an ingenious bit of musical onomatopoeia, with piccolos whirring over a rhythmically steady accompaniment to imitate the workings of a clock. JOSEPH HAYDN Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, Hob. I:105 A DIFFERENT KIND OF CONCERTO For modern listeners, the concerto is almost always a composition for a single featured instrumentalist, usually in the role of a heroic virtuoso, with orchestral accompaniment. But this modern conception of the concerto was not firmly established until around the beginning of the 19th century. Prior to that, concertos for two or several solo instruments were common. During the second half of the 18th century such works were usually identified by the term “sinfonia concertante.” Mozart produced several works of this kind. His great colleague and friend Joseph Haydn composed only one, but it is of exceptional quality. Haydn wrote his Sinfonia concertante in B-flat early in 1792, during the first of his two celebrated visits to London, where the now famous composer had come to preside over a series of concerts featuring his music. The work employs a solo quartet of oboe, bassoon, violin, and cello, and is cast in the usual three-movement concerto. The first movement is built on themes that are by 28 turns graceful and robust. Haydn, in contrast to the practice of his time, does not hold the solo quartet in abeyance during the initial paragraph, but has it assist the orchestra in setting forth his musical materials. There is a lively interplay among the soloists, and all four of them partake in the cadenza Haydn provides near the end of the movement. This opening is followed by a gentle Andante that finds the solo group in intimate conversation with only the barest orchestral accompaniment. The last movement takes the form of an amusing music lesson. The orchestra begins by offering a vigorous phrase in unison, but immediately the solo violin cuts in. “No, no,” its recitative seems to implore. “Try again.” The orchestra does so, but again the violin interrupts: “Not that way— this way.” And for the remainder of this charming finale the four soloists demonstrate a succession of nimble scales and other figures, which the poor orchestra struggles to imitate as best it can. JOSEPH HAYDN Symphony No. 22 in E-flat major, “The Philosopher” First Performance Unknown, but certainly at Esterháza, the palatial estate of the Hungarian prince Nikolaus Esterházy, in 1764, under the composer’s direction STL Symphony Premiere October 14, 1971, James Levine conducting the only previous performance Scoring 2 English horns bassoon 2 horns strings Performance Time approximately 16 minutes HAYDN IN HUNGARY Before visiting London, Haydn had served as court composer to the Hungarian prince Nikolaus Esterházy. This situation entailed both challenge and opportunity. The Esterházy court orchestra consisted only of a small group of strings with pairs of horns and oboes, a bassoon, and occasional flutes. With these modest instrumental forces Haydn had to produce a continually varied stream of music. The most important result of that process was a series of more than 80 symphonies that Haydn composed during his three-decade Esterházy tenure. With the Esterházy court orchestra as his laboratory, Haydn was able to test his musical ideas. Particularly during the 1760s, he experimented with different types and arrangements of movements, sought unexpected turns of melody and harmony, and deployed his musicians in novel ways. His Symphony in E-flat major, No. 22 in the standard listing of his works, employs all these stratagems. 29 SYMPHONIC ANOMALIES The first unusual feature of this composition is its scoring. Prince Nikolaus’s oboists evidently had English horns at their disposal, and in the present work Haydn used those instruments in place of oboes. (This is the only one of his symphonies in which we find this unusual instrumentation.) The result is an uncommonly rich and deep orchestral sound, some perilously high horn writing notwithstanding. But sonority isn’t the only anomaly. Though the work unfolds in four movements, these do not yield the usual pattern of a Classical-period symphony. Haydn reverses the fast and slow movements normally found at the outset, beginning the piece with a stately Adagio. The initial movement brings another surprise. Here a broad theme for the winds plays over a steadily marching accompaniment by the strings. This theme has the character of a liturgical chant, and both that character and the texture of its setting here recall the chorale prelude, a form widely cultivated by composers during the 17th and early 18th centuries. The reference to this older and “learned” compositional genre, together with the measured gravity of the music, presumably inspired the name “The Philosopher,” by which this symphony is now known. The second movement conveys that bracing energy Haydn so often brought to the fast movements of his symphonies. We then hear a minuet, with a contrasting central episode featuring the distinctive timbres of the winds. This anticipates the colors of the closing movement. Here, rapid-fire horn calls are echoed by the English horns, a striking effect. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, K. 543 A MOZARTIAN MYSTERY In the summer of 1788, Mozart completed three extraordinary symphonies, the last such works he would compose. This “final trilogy,” as it is often called, poses two of the most intriguing and enduring questions of Mozart’s biography: Why did the composer write these works, and did he ever hear them performed? Mozart scholars have proposed several possibilities for explaining the composition of these three late symphonies, but even their most persuasive theories remain unproved for lack of definitive documentary evidence. And so, the mystery of the composer’s last three symphonies remains just that. But of the music’s value there is no doubt. No symphonic compositions of the 18th century surpass the “final trilogy” in strength, intricacy, or beauty, and only Mozart’s slightly earlier “Prague” Symphony and the later “London” symphonies of Haydn even approach them in this respect. Less turbulent and impassioned than the Symphony in G minor, K. 550, and not so outwardly brilliant as the “Jupiter” Symphony, K. 551, the Symphony in E-flat Major, K. 543, has long been the least appreciated portion of the “final trilogy.” It deserves better, for its musical substance and compositional details are scarcely less admirable than those of its more famous siblings. Like the other two symphonies of the “final trilogy,” this work follows the four-movement sequence that by the 1780s had become the usual format of symphonic composition. Unlike them, its plan includes an introduction in slow tempo to begin the first movement. This preface begins in a splendid, 30 even ceremonious, manner, with sonorous chords in formal rhythms punctuated by timpani strokes and falling scale figures. (The latter will reappear, in a more animated context, during the main body of the movement.) The music then becomes quiet and expectant, its mounting sense of anticipation making the onset of the ensuing Allegro all the more effective. There follows a slow movement that begins softly and placidly in the string choir alone. Beginning with its second paragraph, however, Mozart touches on some dark harmonies and stormy textures. The outbursts never last long, though, and the movement as a whole conveys a beautiful and seemingly nocturnal atmosphere. The third movement presents a robust minuet whose central episode uses an Alpine folk dance melody, sung here by the clarinet. Mozart constructs the finale on a single swift and energetic theme, a procedure often used by Haydn in his symphonic finales. This subject proves the source of myriad developments, as Mozart varies and extends his melodic material in characteristically imaginative fashion. Program notes © 2014 by Paul Schiavo Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg Died December 5, 1791, Vienna First Performance Unknown STL Symphony Premiere January 23, 1914, Max Zach conducting Most Recent STL Symphony Performance February 11, 2006, Roberto Abbado conducting Scoring flute 2 clarinets 2 bassoons 2 horns 2 trumpets timpani strings Performance Time approximately 29 minutes 31 BERNARD LABADIE DANIEL, MARY, AND FRANCIS O’KEEFE GUEST ARTIST Bernard Labadie most recently conducted the St. Louis Symphony in April 2013. Bernard Labadie has established himself worldwide as one of the leading conductors of the Baroque and Classical repertoire, a reputation that is closely tied into his work with Les Violons du Roy and La Chapelle de Québec, both of which he founded and continues to lead as music director. With these two ensembles he regularly tours Canada, the U.S., and Europe. Highlights of the 2013-14 season include reengagements with the New York Philharmonic, Kansas City Symphony, New World Symphony, and Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Appearances overseas will include concerts with the Malaysian Philharmonic, Auckland Philharmonia, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, WDR Sinfonieorchester (Cologne), Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Munich), NDR Sinfonieorchester (Hamburg), Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, and a European Tour with Les Violons du Roy. PHILIP ROSS HELEN E. NASH, M.D. GUEST ARTIST Philip Ross made his St. Louis Symphony solo debut in January 2008. Philip Ross grew up surrounded by world-class oboists. His father, Dan, is a well-known oboist and maker of gouging machines, which are highprecision cutting tools essential for reed-making. With at least one of Dan’s machines in every major North American orchestra, Jonesboro, Arkansas is a revolving door of oboists making their pilgrimage to have their machines serviced. Philip Ross holds degrees from the Eastman School of Music and the Chicago College of Performing Arts where he studied with Richard Killmer and Alex Klein respectively. He has made repeat appearances as guest principal oboe of the San Francisco Symphony, toured with the Chicago Symphony, and recorded with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. He also takes part in the St. Bart’s Music Festival. Philip Ross enjoys playing music with his wife and fellow oboist, Laura. The oboe couple welcomed their first child in April 2013. 32 ANDREW GOTT Prior to taking the position of Associate Principal Bassoon of the St. Louis Symphony in 2006, Andrew Gott was Principal Bassoon of the Virginia Symphony Orchestra under the baton of JoAnn Falletta. He has also played Principal Bassoon with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and the Woodlands Symphony Orchestra. He has served on the faculty at the Governor’s School for the Arts, Old Dominion University, Christopher Newport University, and Ball State Bassoon Camp. Gott received his Bachelor of Music from Ball State University and his Master of Music from the Shepherd School of Music at Rice University, where he studied with Ben Kamins. Andrew Gott was born and raised in Bolivar, Missouri. Andrew Gott was a member of the ensemble that most recently performed Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante, in November 2008. KRISTIN AHLSTROM Kristin Ahlstrom joined the St. Louis Symphony in 1996, and was appointed to the Associate Principal Second Violin chair in 2001. She is a member of the Ilex Piano Trio along with her husband, pianist Peter Henderson, and St. Louis Symphony cellist Anne Fagerburg; and is also the violinist of a string trio featuring St. Louis Symphony musicians Shannon Farrell Williams and Bjorn Ranheim. Ahlstrom has played chamber music recitals as well as orchestral concerts as a member of the Sun Valley (Idaho) Summer Symphony since 2001, and has been a guest artist in Indiana University’s Summer Music series every year since 2006. She and her husband live in St. Louis’s South City along with their lively, sweet dog Zinni. Kristin Ahlstrom most recently performed as a soloist with the St. Louis Symphony in January 2008. 33 MELISSA BROOKS Melissa Brooks was also a member of the ensemble that most recently performed Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante, in November 2008. Melissa Brooks has been a member of the St. Louis Symphony since 1992. She is a native of New York City, where from 1977-88 she attended the pre-college division of the Juilliard School. Brooks received her undergraduate degree from the New England Conservatory where she studied with Laurence Lesser. She graduated from both schools with Distinction in Performance. Brooks has performed chamber and solo concerts throughout the country, including a duo concert with the late cellist Janos Starker. She has won numerous awards and honors and was nominated by Leonard Bernstein for an Avery Fisher Career Grant in 1988. Her activities in the community include creating and participating in numerous benefit concerts throughout the year as well as engagement in advocacy work. Melissa Brooks is Missouri Chapter leader for the national organization, Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America. 34 A BRIEF EXPLANATION You don’t need to know what “andante” means or what a glockenspiel is to enjoy a St. Louis Symphony concert, but it’s always fun to know stuff. For example, what does “Hob. I:105” mean? Hob.: “Hob.” is the abbreviation for the Hoboken catalogue of Haydn’s works; Hoboken does not refer to New Jersey or have anything to do with the closing of toll booths, rather, Anthony van Hoboken (1887-1983), who took on the enormous task of compiling the definitive catalogue of Haydn’s many works; Hob. numbers include a roman numeral followed by an Arabic figure PLAYING MOZART: “Symphony No. 39 is a difficult piece for string players, because there is so much character that needs to stand out. It’s operatic. Note lengths need to be precise. We need to listen to each other so much and play together. “Not everyone can play Mozart. People want to vibrate at the end of a line, become more romantic. That doesn’t work for Mozart. The music is very transparent. If you don’t respect the character or the lines, it will make a big mush. “In this symphony Mozart gives the second violins a lot of the main theme. We’re not just accompanying eighth notes. In other works we may be part of the background, or supporting the harmony. In this case we’re pretty much equal.” 35 Dilip Vishwanat EVA KOZMA, ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL SECOND VIOLIN Eva Kozma AUDIENCE INFORMATION BOX OFFICE HOURS POLICIES Monday-Saturday, 10am-6pm; Weekday and Saturday concert evenings through intermission; Sunday concert days 12:30pm through intermission. You may store your personal belongings in lockers located on the Orchestra and Grand Tier Levels at a cost of 25 cents. Infrared listening headsets are available at Customer Service. TO PURCHASE TICKETS Cameras and recording devices are distracting for the performers and audience members. Audio and video recording and photography are strictly prohibited during the concert. Patrons are welcome to take photos before the concert, during intermission, and after the concert. Box Office: 314-534-1700 Toll Free: 1-800-232-1880 Online: stlsymphony.org Fax: 314-286-4111 A service charge is added to all telephone and online orders. Please turn off all watch alarms, cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices before the start of the concert. SEASON TICKET EXCHANGE POLICIES If you can’t use your season tickets, simply exchange them for another Wells Fargo Advisors subscription concert up to one hour prior to your concert date. To exchange your tickets, please call the Box Office at 314-5341700 and be sure to have your tickets with you when calling. All those arriving after the start of the concert will be seated at the discretion of the House Manager. Age for admission to STL Symphony and Live at Powell Hall concerts varies, however, for most events the recommended age is five or older. All patrons, regardless of age, must have their own tickets and be seated for all concerts. All children must be seated with an adult. Admission to concerts is at the discretion of the House Manager. GROUP AND DISCOUNT TICKETS 314-286-4155 or 1-800-232-1880 Any group of 20 is eligible for a discount on tickets for select Orchestral, Holiday, or Live at Powell Hall concerts. Call for pricing. Outside food and drink are not permitted in Powell Hall. No food or drink is allowed inside the auditorium, except for select concerts. Special discount ticket programs are available for students, seniors, and police and public-safety employees. Visit stlsymphony.org for more information. Powell Hall is not responsible for the loss or theft of personal property. To inquire about lost items, call 314-286-4166. POWELL HALL RENTALS Select elegant Powell Hall for your next special occasion. Visit stlsymphony.org/rentals for more information. 37