As an engineer, I

looked forward

to taking a

writing class

amid my heavy

math and

science course

load. Professor

Erol’s Writing

101 class, “Visualizing Medicine,”

initially caught my eye because of

its science-based curriculum. When

brainstorming for ideas to write

about, I immediately thought of my

family’s history of chronic illness.

My mother was just diagnosed with

breast cancer a little more than

a year ago and my grandmother

passed away from breast cancer, so

the topic definitely struck a chord

with me. In having such a strong

connection to the disease, I have

paid special attention to breast

cancer advertisements, especially

the pink ribbon campaigns for

breast cancer research. For a textual

analysis assignment, I chose to

examine the dichotomy between

breast cancer images, specifically

focusing on a National Geographic

image I had come across that

seemed to stand out from the rest.

In writing my final analytical paper,

I decided to expand on the topic

and analyze four distinct breast

cancer narratives prevalent in

today’s culture. The collaborative

editing workshops were extremely

helpful to me in developing my

initial brainstorm into a full-fledged

essay because of the candid feedback

I received from my peers and

professor in every step of the writing

process.

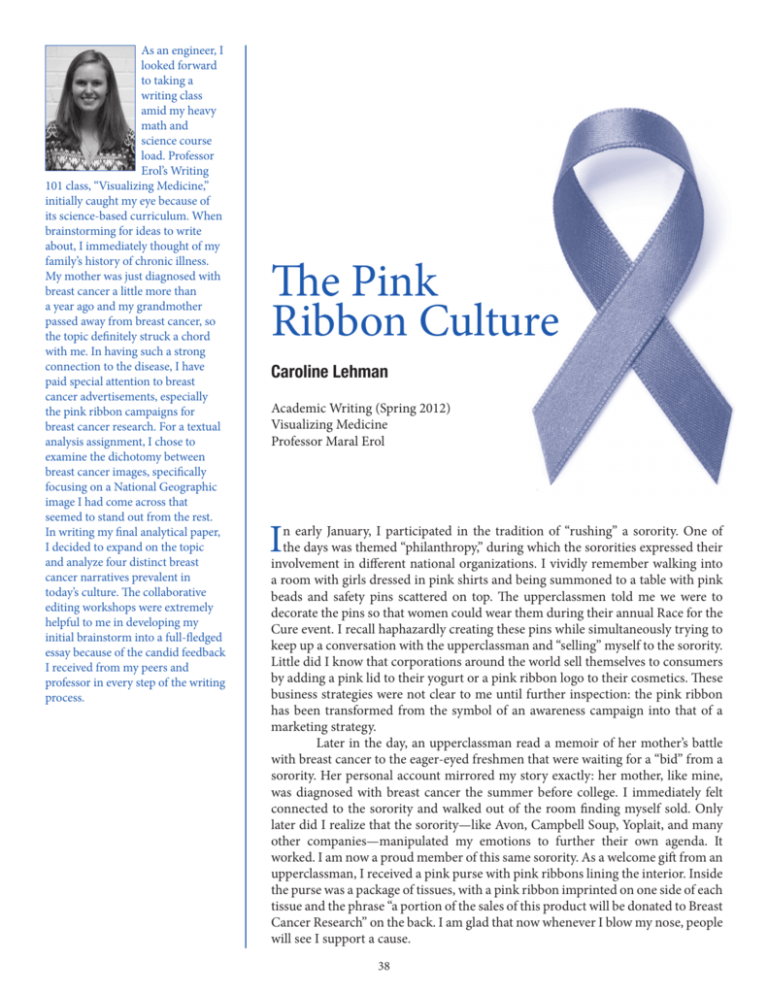

The Pink

Ribbon Culture

Caroline Lehman

Academic Writing (Spring 2012)

Visualizing Medicine

Professor Maral Erol

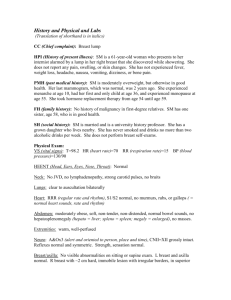

I

n early January, I participated in the tradition of “rushing” a sorority. One of

the days was themed “philanthropy,” during which the sororities expressed their

involvement in different national organizations. I vividly remember walking into

a room with girls dressed in pink shirts and being summoned to a table with pink

beads and safety pins scattered on top. The upperclassmen told me we were to

decorate the pins so that women could wear them during their annual Race for the

Cure event. I recall haphazardly creating these pins while simultaneously trying to

keep up a conversation with the upperclassman and “selling” myself to the sorority.

Little did I know that corporations around the world sell themselves to consumers

by adding a pink lid to their yogurt or a pink ribbon logo to their cosmetics. These

business strategies were not clear to me until further inspection: the pink ribbon

has been transformed from the symbol of an awareness campaign into that of a

marketing strategy.

Later in the day, an upperclassman read a memoir of her mother’s battle

with breast cancer to the eager-eyed freshmen that were waiting for a “bid” from a

sorority. Her personal account mirrored my story exactly: her mother, like mine,

was diagnosed with breast cancer the summer before college. I immediately felt

connected to the sorority and walked out of the room finding myself sold. Only

later did I realize that the sorority—like Avon, Campbell Soup, Yoplait, and many

other companies—manipulated my emotions to further their own agenda. It

worked. I am now a proud member of this same sorority. As a welcome gift from an

upperclassman, I received a pink purse with pink ribbons lining the interior. Inside

the purse was a package of tissues, with a pink ribbon imprinted on one side of each

tissue and the phrase “a portion of the sales of this product will be donated to Breast

Cancer Research” on the back. I am glad that now whenever I blow my nose, people

will see I support a cause.

38

This guise of social activism through consumerism has become especially

prevalent in today’s breast cancer culture. As a consumer, I find myself drawn

to products that prominently display a pink ribbon on their packaging because,

however deceptive it may be, I feel like I make an impact by purchasing that

product. Many companies utilize phrases such as the one on the tissues to advertise

to consumers that they are socially conscious, yet they often do not disclose exactly

how much of the proceeds are donated or where the money actually goes. Breast

Cancer Action, a grassroots education campaign, recently listed forty corporate

marketing campaigns that take advantage of the popularity of the breast cancer

movement to further the company’s own profits (Klawiter, 2008, 250).

The surge of corporate interest in breast cancer research and awareness

first coincided with an increase in breast cancer diagnoses and, in the past decade,

outpaced it. From the 1940’s until the beginning of the 21st century, breast cancer

incidence rates increased an average of 1 percent each year. The rate of breast cancer

cases significantly rose in the 1980s due to an increase in screenings but leveled off

in the 1990s. There has been an apparent decrease of new breast cancer diagnoses

since 2003. Still, in the past two decades, more women have died of the disease

than all Americans killed in World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the

Vietnam War combined

(Eisenstein, 2001, 116).

And while statistics show

that more women die

from heart disease than

breast cancer, according

to professor and breast

cancer survivor Zillah

R. Eisenstein, “it is

breast

cancer

that

women seem to fear

the most” (Eisenstein,

2001, 68). Compared to

other illnesses, breast

cancer is unique in that

it is highly visible in the

media with awareness

campaigns

cropping

up everywhere from

television commercials

to newspapers and

magazines. In fact, breast

cancer has become

one of the most massmediated illnesses of the

21st century (Sulik, 2011,

113). Breast cancer awareness campaigns and images, while seemingly beneficial,

actually devalue the emotions of breast cancer survivors by primarily portraying

breast cancer in an unrealistic fashion.

In looking at breast cancer images over the past two decades, themes of

hope, empowerment, and positivity are omnipresent. In this essay I will analyze

four distinct breast cancer narratives to reveal how America’s present-day breast

cancer culture undermines survivors. The pink ribbon serves as the dominant

symbol in breast cancer culture and is exploited by companies as well as nonprofit

organizations to raise awareness and money for research. Breasts are also

inextricably tied to the cause and are often sexually objectified by the media in

association with breast cancer awareness. Conversely, mastectomized breasts are

39

“Themes of hope,

empowerment,

and positivity are

omnipresent. ”

rarely depicted, as they remind viewers of the horrors of breast cancer and that the

disease does not discriminate (Casamayou, 2001, 104). When audiences see images

of cancer treatments, such as mastectomies, they remember that breast cancer can

strike anyone at any time, especially females. Similarly, rare are the images of anger

and blame toward possible environmental factors of breast cancer.

Case Study 1: The Pink Ribbon

Copyright has expired.

From the New York Times, December 22, 1996 ©1996. The New

York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing,

copying redistribution, or transmission of this Content without

express written permission is prohibited.

As evidenced in the logo for the Susan G. Komen Foundation, breast

cancer cannot escape association with the feminine pink ribbon. This image is

prominently displayed at the top of the Susan G. Komen for the Cure website, the

fifth website that pops up when one types the words “breast cancer” into Google.

Although the pink logo is subdued and does not explicitly state that the ad supports

breast cancer funding, audiences, as well as the search engine Google, immediately

link the pink ribbon with breast cancer and the Susan G. Komen brand. Komen

introduced its new “running ribbon” logo in 2007 in hope of developing a stronger

brand association and a dominant hold over the breast cancer market, such as

survivors and researchers, as well as the pink ribbon culture (Sulik, 2011, 150).

The pink ribbon is central in most breast cancer campaigns, serving as a

reminder for women to exercise, remain nutritionally healthy, and stay proactive

about detection (Eisenstein, 2001, 129). As seen in the logo for the Race for the

Cure event, the pink ribbon moves forward like a runner trying to cross a finish line

or a cancer patient trying to complete a chemotherapy treatment. This symbolism

reveals the themes of hope and positive thinking that are pervasive within breast

cancer culture. According to Barbara Ehrenreich, “positive thinking seems to be

mandatory in the breast cancer world, to the point that unhappiness requires a kind

of apology” (Ehrenreich, 2009, 26). While the pink ribbon symbolizes a person,

there is no actual depiction of a person struggling to survive. Instead, the

feminine curvature of the ribbon serves as a link to the curvature of a woman’s

body. Even the words “Susan G. Komen for the Cure” that accompany the Race

for the Cure logo have arched, rounded letters, giving off a girly, positive, and

lighthearted aura. The foundation is named after Komen and its logo similarly

emphasizes one woman’s name rather than the collective of women fighting

breast cancer. The lone “running ribbon” further characterizes the struggle

with disease as a singular one, revealing the isolation some women may feel in

their fight against breast cancer.

The two tones of pink within the ribbon stand in stark contrast to the bold,

black text. Breast cancer’s association with the color pink makes perfect sense, as

pink is most heavily associated with femininity. The color pink was first linked

with breast cancer in 1990, when Nancy Brinker founded the Susan G. Komen

Breast Cancer Foundation and the Race for the Cure. Initially, pink visors were

handed out to women, signifying that they were breast cancer survivors. The

movement quickly grew, however, and pink ribbons were handed out to every

participant in the Race for the Cure. Estée Lauder immediately recognized

the opportunity for commercial success and joined the effort by launching a

national pink-ribbon campaign in 1992. According to Lauder, “there had been

no publicity about breast cancer, but a confluence of events—the pink ribbon,

the color, the press… having Estée Lauder as an advertiser in so many magazines

and persuading so many of my friends who are health and beauty editors to do

stories about breast health—got people talking” (Associated Press, 2011). Estée

Lauder wanted to partner with Charlotte Haley, a 68-year-old grassroots activist

who handed out peach ribbons to promote funding for breast cancer prevention.

While Lauder offered Haley national attention, Haley wanted nothing to do with

the commercialization. From its inception, the pink ribbon rapidly transformed

from a personal emblem of survival to a method of furthering corporate agendas.

Today, the ribbon not only symbolizes breast cancer survivors, but also embodies

40

the entire community of women afflicted by breast cancer, as well as awareness,

research, and support for the cause (Elliott, 2007).

Case Study 2: This Year’s Hot Charity

It was not long after the inception of the pink ribbon and the creation of

multiple breast cancer nonprofit organizations that the disease became a national

headline. In 1996, The New York Times Magazine ran a quite controversial cover,

shown at left, concerning the rapid rise in attention being paid to breast cancer.

Instead of using an image of women’s empowerment, the magazine’s editors decided

to run a picture of an overly sexualized half-naked supermodel posing as the face

for “This Year’s Hot Charity,” breast cancer. Having a famous model rather than

an unknown cancer patient pose for the cover, the magazine used the practiced

approach of associating a familiar face with the disease to attract more attention

to the cause (Casamayou, 2001, 105). As the cover photo vaguely hints, the article

discusses how breast cancer quickly transformed into a “chic” enterprise, one in

which wealthy individuals, CEOs, and politicians could take part (King, 2006, viii).

The cover does not explicitly indicate that breast cancer is the topic

of interest except for the fact that the naked model is covering up her breasts.

Surprisingly, there is not even the slightest trace of the color pink or a pink ribbon.

The image clearly sexualizes the female figure, with the model’s body glistening

and her mouth slightly open. The model looks unhealthily skinny with some of her

ribs visibly sticking out. Images that sexualize the female body like this one does

are unfortunately prevalent in breast cancer culture. Breast cancer is unique among

illnesses in that it continues to mirror socially sanctioned forms of discrimination

against women (Ferguson et al., 2000, 365). Unlike people diagnosed with heart

disease or other cancers, breast cancer patients continually hear social messages

that they will lose their gender identity and sexuality if diagnosed with the oftdisfiguring disease. This image perpetuates the stereotype that women are purely

sexual beings and reaffirms societal gender expectations.

In the foreground of this image are a man and woman in formal attire, attire

that would perhaps be worn to a large gala fundraiser for breast cancer research.

Their hidden faces emphasize anonymity, paralleling that of large corporations

which can hide behind carefully constructed smokescreens of donating large

amounts of money to nonprofits. As the image and article suggest, it has become

fashionable for corporations to appear to “think pink,” especially since strategic

corporate philanthropy improves public relations and builds consumer loyalty

(Sulik, 2011, 128). The strategy of using the body of a supermodel reflects the

common use of celebrity in American culture, as well as breast cancer culture, as a

way to further promote products and ideas.

Case Study 3: You Can’t Look Away Anymore

Just three years earlier, in 1993, The New York Times Magazine ran a cover

story depicting the breast cancer activist and artist Matuschka and her mastectomy

scar. The article was dedicated to the “Anguished Politics of Breast Cancer” and the

rapid rise of the National Breast Cancer Coalition (NBCC), a feminist lobbying

organization founded in 1991. It details the agenda of the NBCC and its ambitious

goals of garnering more scientific and governmental attention to prevention,

expanding the federal budget for research, and increasing the influence of breast

cancer survivors over the federal research agenda (King, 2006, viii).

Matuschka, like the headline boldly states, looks away from the audience,

almost ashamed of her condition. She is dressed in all white, signifying an innocence

and purity that coincide with womanhood and femininity. However, her innate

femininity is lost due to her invasive breast cancer treatment. In today’s society, like

in the 1990s, it is a cultural taboo to amputate the part of our bodies associated with

maternity and sexuality. Therefore, for many in U.S. culture, mastectomies are an

41

Photo courtesy of Peter Essick

assault on beauty and a violation of femininity (Potts, 2000, 44).

Even though Matuschka’s face is turned away, her powerful gaze and

dominant posture instigate a sense of hope and empowerment among readers.

She wears a dress, emphasizing that while half of what makes her “feminine” may

be gone forever, her sense of womanhood will never be lost. The flowing white

headscarf, an article of clothing usually worn by women who have lost their hair

due to chemotherapy treatment, serves as a symbol of endurance, survival, and

unity among breast cancer patients.

Unlike the pervasive narrative of the sexualized female body seen in Case

Study 2, this image portrays a mastectomy scar. In a culture in which breasts are

“concealed, revealed, adorned

and exhibited primarily for and

from a male point of view” (Potts,

2000, 40), images of anything

other than large, voluptuous

bosoms are rare in popular

magazines. In a study conducted

during a three-year period,

which analyzed over 800 breast

cancer images in newspapers,

only two pictures were found of

mastectomized breasts (Potts,

2000, 43). Mastectomy images are

not prevalent in media because

audiences would rather not be

reminded that cancer can strike

anyone at any time, no matter how

proactive one is in getting routine

mammograms or performing

monthly breast self examinations.

Through these images, women are

told that they are vulnerable and

are reminded of the seriousness

of their responsibility to perform

breast examinations to prevent death. Yet, studies show that while self-examinations

increase the likelihood of detecting cancerous tumors early, it does not cut the

chances of dying from breast cancer (Kösters, 2003).

Case Study 4: Breast Cancer Survivors

An image found on National Geographic magazine’s website, above left,

shows three women from Richmond, California, all of whom have been diagnosed

with breast cancer. A blurb accompanying the photo discloses that the women are

trying to force a nearby oil refinery to reduce its emission of excess gases into the

atmosphere, gases that most likely contributed to their cancer. The woman in front,

Marleen Quint, holds a portrait of herself naked, disclosing the mastectomy she has

undergone to combat the cancer, a procedure that altered her body forever. “My

mother is 79 and has all her body parts,” describes Quint, who suspects that living

near the oil refinery was a major contributor to her cancer. The photo plays with

the emotions of the audience, hitting a nerve with those who know all too well what

it is like to have friends and family members left disfigured by the scars of breast

cancer. Even among people who do not have any connection with the disease, the

photo is so shocking and unusual that it strikes a chord with them.

This photo is unique amid breast cancer images in that it depicts anger. It is

a call to action, expressing the need for the corporate world to take a stand against

oil refineries and factories that emit toxic and often extremely harmful pollutants

42

into the atmosphere. Pink ribbons are nowhere to be seen in this image. Instead, the

women are portrayed as survivors, fiercely fighting for their lives in a war against

cancer. In a breast cancer culture in which being upbeat and positive is the norm,

this photo is refreshing in that it ignites anger and fury, rather than passivity, in me

and presumably in its audience.

Discussion and Conclusion

In analyzing the dominant narratives in breast cancer culture, those of the

pink ribbon and the sexualized female body, similar themes of hope, courage, and

optimism are evident. According to Dr. Susan J. Ferguson, “the pervasiveness of

these kinds of depictions implicitly sends the message that feeling sad, angry, and

entirely unlucky to have breast cancer are not appropriate responses” (Ferguson,

2000, 318). While optimistic images in breast cancer culture are extremely

prevalent, they do not accurately represent the struggle breast cancer patients

undergo every day in battling their disease. There is a large disconnect between

society’s expectations for women diagnosed with breast cancer and women’s actual

experiences with the illness (Ferguson et al., 2000, 364). Barbara Ehrenreich, author

of Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking has Undermined

America, reveals what she first saw when walking into the doctor’s office for a routine

mammogram. “Almost all of the eye-level space had been filled with photocopied

bits of cuteness and sentimentality,” she writes, “pink ribbons, a cartoon about

a woman with iatrogenically flattened breasts, an ‘Ode to a Mammogram,’ a list

of the ‘Top Ten Things Only Women Understand’ (‘Fat Clothes’ and the ‘Eyelash

Curlers,’ among them), and, inescapably, right next to the door, the poem ‘I Said a

Prayer for You Today,’ illustrated with pink roses” (Ehrenreich, 2009, 16). In seeing

this overwhelming cheerfulness and femininity among the décor, Ehrenreich, who

learned that day that she had breast cancer, immediately felt the looming sense that

she must stay upbeat about her diagnosis. Because the positive pink ribbon symbol

is inescapable in breast cancer culture, some patients, like Ehrenreich, feel isolated

in their disease, especially if they do not experience feelings of cheerfulness. In fact,

Ehrenreich felt quite the opposite of hope after prognosis; she instead felt anger

toward the possible environmental causes of her disease.

The alternative narratives—the environmental narrative, and mastectomy

imagery—are scarce in breast cancer awareness campaigns, but portray important

themes of empowerment, activism, and social justice as well as stronger feelings

of anger. Even though some alternative breast cancer campaigns are beginning to

emerge, we must make greater strides to promote activism rather than passivism

while we simultaneously shift away from the overwhelmingly positive pink ribbon

culture. As one breast cancer survivor said, “We used to march in the streets, now

we run for a cure” (King, 2006). Whether we are running for a cure, wearing a

pink ribbon, or purchasing dog food to benefit breast cancer research, we passively

support a cause. The fact is, our passive consumerism does not raise awareness

for breast cancer nor does it help herald a safer environment free of toxic, cancercausing chemicals.

By choosing Yoplait yogurt over another brand in hope of making an

impact, we are submitting to the agendas of large businesses. Many breast cancer

survivors feel undermined by companies’ use of breast cancer to increase their

revenue. As one woman proclaimed, “It’s almost like our disease is being used for

people to profit” (King, 2006). While action should be taken to eliminate corporate

interests profiting from the disease, it is admittedly difficult due to the fact that

large corporations fund breast cancer research. However, the corporate funding

for breast cancer research is not necessarily the problem; it is the crass marketing

of it. These companies spread awareness, advocate for women to perform selfexaminations and to regularly get mammograms, and raise millions of dollars each

year for research. In a way, these corporations do more good than harm in the long

43

“Our passive

consumerism does

not raise awareness

for breast cancer nor

does it help herald

a safer environment

free of toxic, cancercausing chemicals.”

run. Nevertheless, as consumers, we can do our part by becoming more aware of the

lies we are being fed when we walk into the store during Breast Cancer Awareness

Month, or, as it more accurately should be called, National Cancer Industry

Awareness Month. Companies must be more proactive in clearly indicating exactly

how much money is donated and where the money will go so that we as consumers

can make more informed decisions.

Now, whenever I go to blow my nose and see the pink ribbon staring

me in the face, I am reminded of my passive contribution to the pink ribbon

culture that undermines breast cancer survivors’ agency. Social change starts with

exposing the misconceptions and false messages women often receive about breast

cancer. Society must begin to acknowledge the full range of women’s breast cancer

experiences, recognizing not just the dominant positive narrative of survival but

also the stories of outrage and struggle. In order to do this, media portrayals of

women with breast cancer must begin to change drastically.

Bibliography

Associated Press, Fox News. (2011 November 13). Evelyn Lauder, Creator of Cancer’s Pink Ribbon,

Dies at 75. Retrieved July 27th from http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/11/13/evelyn-lauder-creatorcancers-pink-ribbon-dies-at-75/.

Casamayou, M. H. (2001). The politics of breast cancer. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University

Press.

Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How the relentless promotion of positive thinking has undermined

America. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Eisenstein, Z. R. (2001). Manmade breast cancers. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Elliott, C. (2007). Pink!: Community, contestation, and the colour of breast cancer. Canadian Journal

of Communication, 32 (3/4), 521-536. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/2196037

97?accountid=10598

Essick, Peter. (Photographer). (2012). Breast Cancer Survivors [Photograph], Retrieved

February

10th,

2012,

from:

http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/photos/cancer/#/breastcancer_854_600x450.jpg

Ferguson, S. J., Kasper, A. S., and Love, S. M. (Eds.). (2000). Breast cancer: Society shapes an epidemic.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

King, S. (2006). Pink ribbons, inc.: Breast cancer and the politics of philanthropy. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Klawiter, M. (2008). The biopolitics of breast cancer: Changing cultures of disease and activism.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kösters, J. P., Gøtzsche, P. C. (2003). Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early

detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003 (2). Retrieved from http://

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003373/abstract;jsessionid=2B813135E290F275C

69C5F223799A4C9.d01t03

[Logo for Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure]. Retrieved February 20th, 2012 from:

http://ww5.komen.org/

Potts, L. (Eds.). (2000). Ideologies of breast cancer: Feminist perspectives. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Sulik, G. A. (2011). Pink ribbon blues: How breast cancer culture undermines women’s health.

New York: Oxford University Press.

[The New York Times Magazine August 15, 1993]. Retrieved March 20th, 2012 from:

http://oldmags.com/issue/New-York-Times-Magazine-August-15-1993

[The New York Times Magazine December 22, 1996]. Retrieved March 20th, 2012 from:

http://oldmags.com/issue/New-York-Times-Magazine-December-22-1996

44