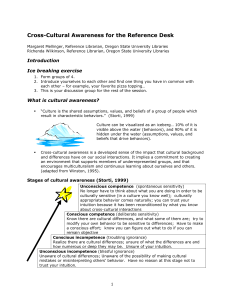

cross-cultural training

advertisement