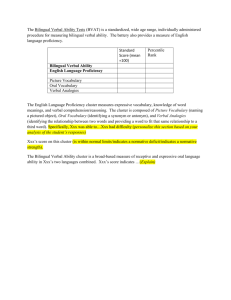

Verbal proficiency as fitness indicator: Experimental and

advertisement