a temporal perspective of corporate m&a and alliance portfolios

advertisement

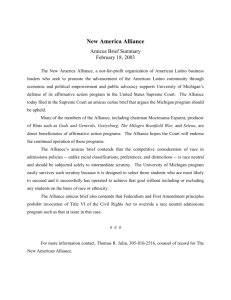

A TEMPORAL PERSPECTIVE OF CORPORATE M&A AND ALLIANCE PORTFOLIOS John E. Prescott and Weilei (Stone) Shi ABSTRACT How and whether the rhythm, synchronization and sequence of firms’ M&A and alliance activity over time impact firm performance is our core question. We seek to advance a temporal lens in the M&A and alliance discourse by explicitly incorporating time-associated theories, constructs and methods. A temporal view of M&A and alliance activity requires strategists to study fundamental questions related to when and under what conditions firms should accelerate, slow down and coordinate their M&A and alliance initiatives, whether firms’ trajectory of M&A and alliance have discernible and distinctive patterns over time, and whether these initiatives demonstrate a temporal pattern that becomes an integrated part within firms’ M&A and alliance routines that create a time-based source of competitive advantage. Using a sample of 57 small to mediumsize firms in the global specialized pharmaceutical industry and their M&A and alliance activities for 19 years we find support for our temporal-based hypotheses. Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, Volume 7, 5–27 Copyright r 2008 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1479-361X/doi:10.1016/S1479-361X(08)07002-6 5 6 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI INTRODUCTION How and whether the rhythm, synchronization and sequence of firms’ M&A and alliance activity over time impact firm performance is the core question of our on-going research agenda. Our objective is to advance a temporal lens (Ancona, Goodman, Lawrence, & Tushman, 2001) in the M&A and alliance discourse by explicitly incorporating time-associated theories, constructs and methods. A temporal view of M&A and alliance activity focuses our attention towards questions related to when and under what conditions firms should accelerate, slow down and coordinate their M&A and alliance initiatives, whether firms’ trajectory of M&A and alliance initiatives have discernable and distinctive patterns over time, and whether these initiatives demonstrate a temporal pattern that becomes an integrated part of firms’ M&A and alliance routines that create a time-based source of competitive advantage. While there are a variety of temporal theories constructs and approaches, we focus on rhythm, synchronization and sequence because they directly address the above-mentioned time-based questions that are central to the M&A and alliance literature. We define rhythm as the pattern of variability in the intensity and frequency of M&A and alliance activity (McGrath & Kelly, 1986; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Synchronization or mutual entrainment is the adjustment of one activity to match with that of another (Ancona & Chong, 1996). We explore both internal synchronization of M&A and alliance initiatives and the external synchronization of these strategic initiatives with competitors. The sequence of a firm’s M&A and alliance activity is the trajectory of the incidence of these activities over a specific period of time, their timing and duration and the transition between the two activities. In this chapter, we first articulate the value of adopting a temporal perspective in the M&A and alliance dialog. Next we present in narrative form the theory, methods and results for three research projects related to our research agenda. Finally, we speculate on fruitful M&A and alliance time-based initiatives. THE VALUE OF INCORPORATING A TEMPORAL LENS IN THE M&A AND ALLIANCE DIALOG While the M&A and alliance literatures have a rich and diverse tradition, a temporal perspective focusing on the rhythm, synchronization and sequence A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 7 of M&A and alliance initiatives has received scant attention. At this point, you might be asking yourself questions such as whether firms consciously and deliberately develop a rhythm for their M&A initiatives or whether firms synchronize their M&A and alliance activities with competitors. As we explored these assumptions, we ran across the following quote from Mike Tomlin, Head Coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers: ‘‘We’re thoughtfully non-rhythmic’’.1 While Coach Tomlin was not referring to M&A or alliances, his quote is consistent with our perspective that managers can intentionally conceptualize and implement time-based approaches for important decisions. A temporal dimension of strategy is embedded in a wide range of phenomenon, including, but not limited to first mover advantage (Lieberman & Montgomery, 1988), resource-based view (Dierickx & Cool, 1989), dynamic capabilities (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997), decision making under uncertainty (Eisenhardt, 1989), change management (Huy, 2001) and the real option perspective (Kogut, 1991). While these research streams have provided significant practice and process insights, their central focus has not addressed temporal constructs such as tempo, cycles, rhythm, synchronization and sequence (with some notable excepts such as time-based competition). A fundamental underpinning of strategic management logic lies in a prevailing focus on substance, i.e. what to do, over temporality, i.e. when, how fast, how often and how frequently to do. Thus, the temporality of strategy is relegated to a peripheral role (Ancona et al., 2001) in that time-associated constructs and assumptions are not explicitly developed but implicitly assumed (Butler, 1995) and often employed as methodological proxies for other constructs of interest. For example, in the top management team literature, tenure is a methodological proxy for firm or industry knowledge, group cohesion, inertia and harmonious working relationships (Mosakowski & Earley, 2000). In the alliance literature, repeated partnering with the same firm is a proxy for trust and positive working relationships (Gulati, 1995). There are some important exceptions with respect to our focus in the M&A and alliance streams, for example, questions related to accelerating or slowing down post-acquisition integration (Homburg & Bucerius, 2006), preemptive acquisition (Carow, Heron, & Saxton, 2004), M&A and alliance experience relationship with performance (Haleblian & Finkelstein, 1999) and M&A and alliances as learning tools and races (Hamel, 1991). While these different thrusts offer unique contributions for enhancing our temporal understanding of M&A and alliance initiatives, two important temporal issues remain under-developed. First, their focus typically centers 8 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI on a single M&A or alliance and therefore does not incorporate the nature of multiple strategic initiatives and their interplay. In other words, they are not approached from a portfolio perspective (Hoffmann, 2007). Second, those scholars that have recognized the interdependent nature among multiple M&A and alliances (Haleblian & Finkelstein, 1999) have not addressed their periodicity and the fact that multiple initiatives can occur synchronously at the same level of analysis (e.g. firm) or across levels of analysis (firms and their competitive environment). In other words, M&A and alliance initiatives can demonstrate a discernable pattern in the timing of their occurrences conditioned by internal or external pacers. Thus, a temporal lens of M&As and alliances calls for theoretical development and empirical examination of temporal constructs. From our perspective, a temporal lens of M&As and alliance portfolio development can contribute to the enrichment of our understanding of these strategic initiatives in at least four ways. First, studying temporal constructs such as rhythm, synchronization and sequence addresses the fundamental concerns of strategy, i.e. how firms behave and why firms differ (Rumelt, Schendel, & Teece, 1994). In particular, a temporal view that emphasizes the role of rhythm, synchronization and sequence suggests a past–present–future link (when to do) and is in line with the conceptualization of strategy as emergent, dynamic, logically incremental, path dependent and patterns of interaction (Mintzberg, 1990; Ofori-Dankwa & Julian, 2001). Second, temporal constructs such as internal and external synchronization of M&As and alliance initiatives help us to better understand and model them as multi-level phenomenon which is consistently called for in strategy research (Pettigrew, 1992). Theoretical approaches such as the entrainment model (which is the core theory behind the concept of rhythm) provide a theoretical explanation for why firms coordinate rhythmic M&A and alliance processes within the boundaries of their firms as well as their interactions with their environment. As such, the entrainment model among others (Ancona & Chong, 1996) serves as theoretical foundation for studying multiple activities, multi-level phenomena and their interactions across time. Viewing M&As and alliances from multiple activities and multi-level phenomena is important since they can be viewed as two separate activities that have different momentums, rhythms and trajectories. Alternatively, viewing M&As and alliances as internally (within firm) embedded is consistent with the call for an explicit understanding of A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 9 multiple activities at the same level of analysis. Alignment and coordination between activities, as Powell (1992) concluded, can become a competitive advantage. Third, a temporal view that focuses on theoretical concepts such as rhythm, synchronization and sequence of M&As and alliances complements the opportunity-driven perspective. In this regard, a temporal strategy is particularly important for small- and medium-sized firms since they typically have limited capabilities across their industry value chain and have not developed specialized corporate development offices. As we noted above, a rhythm-driven approach is based on an assumption that managers purposely plan and implement M&A and alliance activities. In large corporations, corporate development offices staffed with analysts often assume this role (Kale, Dyer, & Singh, 2002). In the context of small- and medium-sized firms, corporate development offices are not common or economically feasible, yet these firms often undertake multiple M&A and alliance initiatives. We propose that small- and medium-sized firms are likely to adopt a rhythm-driven M&A and alliance (and more generally a temporal) approach under two interrelated circumstances. For firms whose growth strategies are mostly driven by M&A and alliance initiatives, one would expect to see a rhythm-driven approach. In addition, firms who lack capabilities or resources for internally generated growth will adopt a rhythm-based approach to M&A and alliances. Either as a conscious choice or due to limited resources, many small- and mediumsized firms that lack capabilities to internally develop new products will proactively search for targets and allying partners rather than passively wait for M&A and allying opportunities to emerge. Later in this chapter, we share interesting finding regarding our rhythm example in the context of small- and medium-sized global specialty pharmaceutical firms. Lastly, a temporal perspective of M&A and alliances provides a fresh view for the static vs. dynamic strategic fit debate (Zajac, Kraatz, & Bresser, 2000). For instance, the theoretical approach underlying our rhythm and synchronization studies asserts that M&A and alliance activities are embedded and interdependent, and that a fit should be achieved by matching M&A and alliance activities across time. This serves two purposes in clarifying the fit debate. On the one hand, incorporating time constructs explicitly (rather than as methodological proxies) helps to explain the dynamics of why and how outcomes are differentially shaped by multiple on-going activities. Second, we argue that fit has an inherent temporal 10 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI characteristic that influences and is influenced by multiple activities within and external to firms. M&A AND ALLIANCE RESEARCH: A TEMPORAL LENS RESEARCH AGENDA While there are several temporal constructs, the selection of rhythm, synchronization and sequence builds on and complements the extant literature in several ways. First, the prevalence of active acquirers (Laamanen & Keil, 2008) and alliance portfolios (Lavie, 2007) indicates that companies, rather than executing isolated deals or alliances, often execute a serial of mutually interrelated acquisitions or alliances over time. Paradoxically, prevailing research centers on individual acquisition or alliance. There are few theoretical lenses that can accommodate multiple or a series of acquisitions and/or alliances. A temporal lens that focuses on rhythm, synchronization and sequence has the potential to offer a systematic theoretic foundation that directs our empirical examination. For instance, when firms engage in more than one acquisition, both its short- and long-term performances are not longer driven by an individual acquisition or alliance, but rather by the overall pattern and structure of the strategic portfolio over time (Koka & Prescott, 2002). Temporal constructs such as sequence provide a sociological foundation for why firms’ strategic initiatives do not occur in infinite combinations but rather in a limited set of types or what is often referred as typologies or taxonomies. Typologies such as Miles and Snow (1978) have played an important role in the strategy field and a temporal-based typology of M&A and alliance initiatives would be a valuable contribution to the field. Second, our three constructs have been studied extensively in other fields such as sociology and organization behaviors, but have only recently attracted the interest of strategy scholars (Laamanen & Keil, 2008; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Third, the constructs demonstrate one way to organize firms’ M&A and alliance initiatives along a time dimension which captures their historical and holistic M&A and alliance momentum. In the next section, we provide an overview of our sample and its appropriateness for our research questions. We then develop our theoretical reasoning and empirical support for a set of hypotheses linking rhythm, synchronization and sequence to performance. We use a narrative form to present our findings. Scholarly papers are available for each of the A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 11 studies we present below as well as one on pacing and M&A and alliance initiatives. INDUSTRY CONTEXT AND SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS We used the global specialized pharmaceutical industry as the context to examine our temporal-based hypotheses. Our sample consisted of 57 small to medium-size firms (SME’s) and their M&A and alliance activities for 19 years beginning in 1985 and ending in 2003. We carefully selected our sample firms applying the following procedure. First, we identified firms that have value chain activities in the pharmaceutical industry (SIC 2834). We also identified key words such as special drug and specialty pharmacy, and searched company websites, annual reports and major industry journals for potential firms to include in our sample. We then narrowed the sample to firms that were listed on either the NYSE or NASDAQ because we explore performance implications. Finally, we had two pharmaceutical industry experts provide an assessment of our sample as a validity check. The global specialized pharmaceutical industry provides an excellent context for us to study firms’ M&A and alliance temporal behavior. Smalland medium-sized specialized pharmaceutical firms’ growth strategies are largely driven by M&A and alliances activities. As we mentioned above, firms utilizing M&A and alliance growth-driven strategies provide an ideal context to study temporal constructs such as rhythm, synchronization and sequence. Specialty pharmaceutical firms often do not possess the requisite complementary skill sets and knowledge for in-house development activities; they instead rely on partner firms for important resources. The lack of internal capabilities to develop therapeutic products suggests that these firms are more likely to search for targets or partners proactively. Their overall M&A and alliance initiatives are less likely to be driven opportunistically. In addition, small, young and specialized firms are regarded as a driving force for industrial renewal and innovation (Audretsch, 1995). Their survival environment is extremely dynamic and competitive advantage often accrues to those firms that can manage the temporality of their collaborative activities (Barkema, Baum, & Mannix, 2002). Finally, most of our SME’s were established around the mid-1980s, when the Securities Data Corporation (SDC) began to collect complete alliance and M&A data. This allowed us to collect a fairly complete history of firms’ M&A and alliance behaviors which is critical to understand firms’ temporal patterns over time. 12 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI We obtained M&A and alliance data from SDC Platinum and verified them through company 10k reports, firm websites and interviews with industry experts. Firm level and performance data were collected from COMPUSTAT industry annual database and from interviews with industry experts. To measure and test the rhythm and synchronization of firms’ M&A and alliances, we employ Kurtosis measure as well as other variability measure. We test our hypothesis of rhythm using econometric models that deal with both autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity. We test our synchronization (fit) hypothesis using traditional difference score analysis and cross-level polynomial regression (combined with hierarchical linear modeling) for internal synchronization and external synchronization, respectively. To empirically identify the sequence pattern of firms’ M&A and alliances behaviors, we transformed the raw data into sequence format, which provide sufficient information on transitions and trajectories over firms’ historical courses on the number of M&As and alliances conducted each year, their timing and transitions between the dominant forms of strategy (M&As or alliances). RHYTHM AND SYNCHRONIZATION IN M&A AND ALLIANCE PORTFOLIOS Rhythm is defined as the pattern of variability in the intensity and frequency of organizational activities (McGrath & Kelly, 1986; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002) and synchronization or mutual entrainment is defined as the adjustment of one activity to match with that of another (Ancona & Chong, 1996). These temporal concepts are largely borrowed from the entrainment model in biologic sciences, in which the notion of entrainment refers to one cyclic process being captured by, and setting to oscillate in rhythm with, another process. McGrath and Kelly (1986) were among the first to introduce the entrainment model in the social sciences. The social entrainment model specifies that psychological and behavioral cycles can become entrained to other social or environmental processes. For example, in universities, the academic calendar and faculty teaching/meetings are entrained. As McGrath and Kelly (1986, p. 80) stated, ‘‘the social entrainment model provides a coherent framework for describing the operation of rhythmic process, their coupling to or synchronization with one another and potentially to outsider cues’’. For the social entrainment model employed here, we define the three temporal constructs in the A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 13 following way: rhythm is the pattern of variability in the intensity and frequency of M&A and alliance initiatives, internal synchronization is the rhythm synchronization between alliances and M&As within firms, and external synchronization is the rhythm synchronization between M&A and alliance activities of focal firms and their competitors. In the M&A and alliance context, rhythm emphasizes the recurring nature of a frequency pattern, i.e. the pattern of variability in the frequency of M&A and alliance initiatives. To this end, our major focus in discussing the rhythm of M&A and alliance initiatives is the variability, consistence and regularity of the pattern across a specified time period. In biology, although there is no rigorous physicochemical explanation for rhythm, two conjectures of rhythmic activity have emerged (Oatley & Goodwin, 1971) and we will draw on them for our synchronization argument. The intrinsic (internal) view (cellular biochemical clock hypothesis) suggests that it is an essential dynamic feature of the observed process. The fundamental periodicities in living systems are the cycle of growth and division in cells, which need bear no relation to any environmental periodicity. The extrinsic perspective (hypothesis of environmental timing of the clock), on the other hand, maintains that such rhythms represent adaptive responses to a periodic environment such as solar, lunar and annual rhythms. Biologic scholars tend to agree that complicated periodic organisms can be understood as partly adaptive and partly of internal origin. The origins of rhythm in corporate strategic actions can be understood in a similar way since the physiological processes of biologic organisms can be applied reasonably well to psychological processes of individual decision makers or to social–psychological mechanisms at the interacting dyads, groups or even larger organized social units (McGrath & Kelly, 1986). Internally, a rhythmic M&A or alliance pattern can be formed through multiple means over time. It can be influenced and shaped consciously by a top management team whose members have some sort of rhythmic orientation intended to achieve economic efficiency. Individuals who are more rhythmic will be more likely to reflect such a mindset in their actions. For example, major PC manufacturers release upgraded products at Christmas time each year in order to take advantage of newly released versions of software (i.e. Microsoft: games) or hardware (i.e. Intel: memory chips). Events such as annual strategic planning create ‘‘repetitive momentum’’ providing a time-based routine for managers to reconsider or revise their M&A or alliance behaviors. In the case of small- to mediumsized specialized pharmaceutical firms in our empirical context, M&A and alliance activity is largely driven by sales gaps.2 As a result, the overall level 14 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI of M&A and alliance is not stable over time, with periods of sped-up activity and slowed-down activity that is consciously driven. From an external perspective, rhythmic M&A and alliance behaviors may be captured or entrained by external cyclic phenomena often reflected in isomorphic (mimicking) behavior. For instance, Jansen and Kristof-Brown (2005) reported that an individual’s work rhythm matches their working environment’s rhythm. Souza, Bayus, and Wagner (2004) found that the optimal rhythm of new product introduction is primarily driven by external industry conditions. M&A and alliance initiatives can also be captured by external competitive dynamics such as competitor initiatives or regulatory change (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). Building on the internal and external drivers of rhythm, the main feature of rhythmic behavior is revealed in stability properties as opposed to duration, magnitude and frequency. The degree of stability or regularity differs across organizations. This can be understood in two extreme examples consistent with the resource-based view that resources and capabilities are distributed heterogeneously among firms (Barney, 1991). On one hand, firms may conduct M&As or alliances without deliberate planning, plotting along the temporal dimension and thus demonstrating a purely random or stochastic process. On the other hand, firms may perceive time as a variable that can be purposely designed and effectively managed, making M&A and alliance activity a temporal regularity within which the pattern persists over time. In other words, firms differ in their capability to design their corporate strategy with respect to time. Clearly, most firms will not fall at the extremes of pure random or pure regularity. The differentiated rhythmic pattern among firms reflects the underlying combination of firms’ distinctive capabilities including, but not limited to, top management team, strategic planning, environmental scanning systems, history and managerial intent. Like the concept of rhythm, the notion of synchronization is largely derived from biologic science. The intrinsic and extrinsic views of rhythm suggested that synchronization can occur both internally and externally. Within an organization, multiple processes are entrained with each other (i.e. synchronized) through conscious decision processes, coordination, repetitive momentum and isomorphic mechanisms (McGrath & Kelly, 1986). Social behavior can be entrained/synchronized to powerful external pacer event or cycles. However, external pacer events or cycles should be understood from an ontological assumption of co-evolution rather than an assumption of independence of the firm and its environment A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 15 (Volberda & Lewin, 2003). We cannot understand these external zeitgebers by separating them on their own since these exogenous forces are often endogenized over time. PERFORMANCE IMPLICATION OF RHYTHM Rhythm can affect performance through its impact on the ability to coordinate internal events (Goodwin, 1970) or increase the predictability and hence the control of human behaviors. Essentially, rhythm creates a dominant temporal order and reflects ‘‘the underlying dynamic equilibrium processes by which the many aspects of complex social systems’’ (McGrath & Kelly, 1986, p. 89) or a series of repeated activities are coordinated. We argue that neither regular/consistent nor irregular/random patterns of M&A and alliance activity will influence performance positively. An effective rhythmic pattern requires organizations to alternate between regularity and irregularity. This suggests that organizations can experience a regular rhythm for a period of time and then adjust their learning speed thereafter. This can be understood from three interrelated theoretical mechanisms. From learning mechanism point of view, regularity can allow companies to absorb knowledge in a habitual temporal order and over time can facilitate the formation of a routine that is an essential element to managing uncertainty. However, regularity seldom allows companies to modify or revise their existing rhythm strategy and is prone to generate inertia (Carroll & Hannan, 1990). Minor adjustments can serve as a benchmark against which an existing rhythm can be compared, revised and modified. A second mechanism is based in a resource availability perspective. A consistent rhythm allows companies to coordinate resource allocation processes in line with M&A and alliance activities. It also makes the resource allocation process more predictable and hence alleviates pressure from unexpected capital investment needs. However, a regular path reduces the diversity of absorptive capability. Regular repetition of similar activities with a fixed variation implies a logic of linearity (Geibler, 2002) and continuity, neither of which is essential building block for creativity. Creative resource allocation processes require freedom, flexibility and diverse forms of absorptive capability Lastly, unlike many internal initiatives which can be shielded from competitors’ attention, M&A and alliances are corporate actions easily caught by competitors’ radars. M&A and alliances can be interpreted by 16 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI competitors as a preemptive strategy to occupy a market or to acquire valuable resources. From an action and reaction or competition mechanism point of view (Grimm & Smith, 1997), a regular pattern of M&A and alliances reduces within-firm variability (unpredictability) and hence the complexity of a firm’s sequence of competitive actions over time. In contrast, regular patterns coupled or alternated with adjustment and modification can increase the possibility of surprise actions, therefore limiting a competitor’s ability to map action and reaction cycles in an accurate or predictable way. Simply put, semi-predictability (or inverted U relationship) generates the highest level of performance. In our empirical investigation, we find an inverted U-shape relationship between the combined rhythm of M&A and alliance initiatives and performance as measured by firm’s Tobin’s Q, i.e. a rhythmic pattern that is characterized by a mixture of regularity and irregularity achieves the highest level of performance. Interestingly, we also find that the curvilinear relationship between rhythm and performance is largely driven by M&As rather than alliances when we de-couple the two types of initiatives. PERFORMANCE IMPLICATION OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL RHYTHM SYNCHRONIZATION While internal rhythm synchronization helps to coordinate internal events (Goodwin, 1970), external rhythm synchronization can create a coordination interface between focal firms and their environment. Such congruence is more likely to be ‘‘satisfying’’ to firms since it creates order and coordinated interaction patterns out of chaos. These effects are transformed into a sense of control with respect to the external environment. Therefore, external synchronous rhythm reduces uncertainty and increases predictability. Rhythm compatibility between firms and the external environment also validates behaviors in a mutually reinforcing manner through which firms feel comfortable due to a ‘‘social norms’’ mechanism (Jansen & Kristof-Brown, 2005). In particular, the alignment of a firm’s rhythms of M&As and alliances with competitors can influence performance through its impact on the perception of other stakeholders. While external rhythm compatibility allows firms to better control their environment and increases the accuracy of predicting the future, internal rhythm synchronization can achieve a similar goal, i.e. more control over A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 17 and predictability of the internal environment. These can be achieved in at least two ways in the cases of M&A and alliance initiatives. First, when M&As and alliance initiatives proceed simultaneously within a firm, it can establish a minimum levels of overlap between each activity. Such an overlap establishes a foundation for a knowledge-sharing mechanism between M&As and alliances. For instance, knowledge acquired from experiential learning in M&As can be shared and utilized in experiential learning of alliances if the underlying knowledge structure (such as target/ partner selection) of M&As and alliances is similar. Second, synchronization of multiple activities can strengthen their cumulative effect. It creates a heightened sense of beginning or of ending for organization members. We suggest that such a heightened sense of time can create an institutionalized temporal map mechanism for members to adhere to and coordinate with. Internal rhythm compatibility smoothes the resource allocation process through deploying resources to the ‘‘right activities at the right time’’. In our empirical testing, we find support for our internal synchronization hypothesis, i.e. when firms synchronize their acquisition and alliance activities, their performance is enhanced. However, as for external synchronization, we only find performance improvements for external synchronization of alliance but not for acquisitions. SEQUENCE IN M&A AND ALLIANCE RESEARCH Sequence is conceptualized as an ordered list of elements (Abbott, 1995), and has been employed extensively by sociologists (Abbott & Hrycak, 1990; Han & Moen, 1999) and discussed widely in the social sciences including political science (Carmines & Stimson, 1986), linguistics (Gisiner & Schusterman, 1992), archeology (Tolstoy & Deboer, 1989), economics (Chand & Chhajed, 1992) and psychology (Pak & Tennyson, 1986), to name a few. The sociological conceptualization of sequence embraces several distinctive features. First, unlike economists, sociologists make no stochastic assumptions, which suggests that sequences need not be generated step by step, as depicted in the psychology and economics literature. The step by step sequence has been widely applied to study the track of occupational professionalization, the development of organizations, the life cycles of individuals or families and the unfolding of revolutions (Edwards, 1927), or any other ‘‘history’’ that can be expressed as a sequential list of events (Abbott & Hrycak, 1990, p. 145). 18 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI Second, the central focus of a sociological view of sequence is nearly always to fish for patterns in the sequences (Abbott, 2000) rather than to seek dependence between sequence states as adopted by many nonsociological works. For instance, sociologists are interested in identifying different trajectory patterns in individual career progression (Abbott & Hrycak, 1990; Halpin & Chan, 1998; Han & Moen, 1999), and in locating different daily routines in time-use analysis (Lesnard, 2004). Such a view explicitly acknowledges that there can be varying degrees of interdependence between various ‘‘whole’’ sequences in addition to the dependence between different states in a single sequence. In other words, sequences are often subject to influence by other sequences. In our study of sequence, the elements of a sequence are ‘‘events’’ (Abbott, 1995, p. 95), which specifically refer to M&A’s and alliances. Of particular interest are firms’ M&A and alliance histories, which provide detailed information on trajectories over a specific period of time in the incidence of M&As or alliances, their timing, duration and the transition between different dominant modes of corporate strategy (M&A and alliance). We explore the issue of sequences by asking three related questions, namely the substantive question, the pattern question, and the generation and outcome question, which are all embedded in the following three goals. The substantive question mainly deals with the rationale of adopting a temporal lens. We argue that understanding the sequence of strategic actions along firms’ trajectories or paths is a central research endeavor in the field of strategy (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985; Van de Ven, 1992). Comparing past histories for a phenomenon to identify patterns is a very natural activity for human beings (Levinson, 1978). Our second goal deals with the search and identification of commonality and dissimilarity among firms in terms of their sequences of M&A and alliance behaviors (the pattern question). In particular, we are interested in constructing gestalts (Miller & Friesen, 1980), or taxonomy3 of firms’ sequences under the assumption that the strategic phenomena of interest do not occur in infinite combinations, at least not with equal likelihood (Hambrick, 1983, p. 214). Lastly, using multivariate analysis, we expect to find differences across pathways or patterns of sequences in terms of firms’ resources, capabilities and performance outcomes (the generation and outcome question) although we embrace the concept of equifinality. In order to explore the sequence patterns in firms’ M&A and alliance histories, we used a sequence analysis technique known as ‘‘optimal matching’’ (Abbott, 1995). The fundamental rationale underlying the use of this dynamic programming technique is to measure sequence resemblance A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 19 when sequences consist of strings of well-defined elements. It is based on an algorithm to measure the distance between each pair of sequences in terms of the insertions, deletions and substitutions required to transform one sequence into another. Essentially, the optimal matching algorithm will generate a dissimilarity matrix, indicating how distant/dissimilar each pair of sequences is. This matrix is then used as an input matrix to the network software UCINET. Hierarchical clustering is performed on this matrix to identify a set of clusters that share similar trajectory patterns. This identification process is analogous to that of using ‘‘structural equivalence’’ (occupying similar positions in a network) to cluster actors in network analysis (Krackhardt, 1990). Put differently, two sequences are temporally equivalent or sequentially equivalent (Han & Moen, 1999) when they share similar patterns of trajectory along the time line. We discerned seven types of distinct clusters based on the clustering analysis (see Table 1). We labeled them ‘‘focused strategy periodic sequence’’ (cluster 1), ‘‘focused strategy irregular sequence’’ (cluster 2), ‘‘synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence’’ (cluster 3), ‘‘single strategy periodic sequence’’ (cluster 4), ‘‘single strategy irregular sequence’’ (cluster 5), ‘‘unitary sequence’’ (cluster 6) and ‘‘cipher sequence’’ (cluster 7). Firms in different clusters tend to develop their M&A (alliance) strategy differently. For instance, firms in cluster 2 (focused strategy irregular sequence) tend to roll out their predominant strategy in a very irregular rhythm, while, in cluster 3, firms conduct alliance and M&A activities simultaneously. Interestingly, these activities are coordinated in a synchronized fashion and are conducted in a well-developed rhythm, i.e. they develop these strategies either periodically or progressively. We also examine characteristics of firms categorized into these seven sequence types and find some distinctive features. For instance, firms following different sequences of M&A and alliance activities differ significantly in terms of asset, profitability and market performance as showed by Tobin’s Q, while different sequence types do not differ significantly on growth or financial leverage. Firms following a synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence (cluster 3) have the highest level of assets, while firms without any acquisitions or alliances (cipher sequence) have the lowest level of asset. Given the nature of SME, most firms have negative profitability, while only firms in focused strategy periodic sequence and synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence have positive return on asset. Our analysis also reveals that investors perceive distinctive sequence types differently. It seems that firms adopting a unitary sequence type (i.e. firms conduct either 39% 25% 21% 64% 40% 55% 19% 32% 6.712 1.697 366.46 1085.66 828.21 191.02 151.18 545.58 547.30 15.998 11.925 Asset Growth 917.82 Asset ($million) 13.571 24% 20% 13% 10.629 31% 20% 1% 2% 6% Profitability 0.378 41% 12% 26% 2.566 96% 54% 4% 2% 22% Financial Leverage 6.572 6.35 3.06 4.10 16.881 6.03 3.38 3.45 3.80 3.56 Tobin’s Q 9.707 6.50 2.87 4.14 25.491 6.40 3.50 3.39 3.78 3.66 71% 65% 52% 86% 25% 20% 43% 0% Tobin’s Q (3-year Stage moving average) 1 Seven Sequence Types and their Characteristics. 29% 18% 33% 0% 75% 40% 29% 100% Stage 2 0% 18% 15% 14% 0% 40% 29% 0% Stage 3 Cluster 1: Adopts predominantly a M&A (alliance) strategy over the alliance (M&A) strategy with a periodic rhythm. Cluster 2: Rolls out their predominant strategy in a very irregular rhythm. Cluster 3: Conducts alliance and M&A activities simultaneously and these activities are coordinated in a synchronized fashion with a well-developed rhythm. Cluster 4: Similar to cluster 1, with the exception that firms in cluster 4 adopt one type of strategy, i.e. either M&A or alliance. Cluster 5: Similar to cluster 1, with the exception that firms in cluster 5 adopt one type of strategy but in an irregular sequence. Cluster 6: Conducted either one alliance or one M&A during that time period. Cluster 7: Never conducted any M&As or alliances during the study period. po0.05; po0.01; po0.001. a Since test of homogeneity of variances was rejected, we therefore use Dunnett’s C procedure to conduce multiple comparison test. Focused strategy periodic sequence (1) Focused strategy irregular sequence (2) Synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence (3) Single strategy periodic sequence (4) Single strategy irregular sequence (5) Unitary sequence (6) Cipher sequence (7) Total Test of homogeneity of variances F-Testa Cluster Table 1. 20 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 21 one alliance or one M&A during the study’s time period) receive significant rewards from investors compared to others (as demonstrated by their Tobin’s Q). More interestingly, our study reveals that firms’ life cycle stage is a crucial factor that shapes firms’ strategic choices of certain sequences over others. Firms adopting a focused strategy periodic sequence type (cluster 1) are found only in a developmental stage. Single strategy periodic sequence (cluster 4) and unitary sequence types (cluster 6) consist exclusively of firms in either the emerging or developmental stages. In general, we observe two patterns in the data. First, on average, there seems to be distinctive M&A and alliance sequences for firms in different life cycle stages. Second, firms in both emerging and developmental stages seem to have quite diverse sequences, whereas established firms’ sequences tend to be much more normalized, and can be categorized primarily into a couple of sequence types. Given that we found that firms’ life cycle stage plays a critical role in their temporal strategy, it is important to study the contingent context under which different sequences impact performance differentially. From a theory building perspective, establishing the relationship between sequence and performance also corresponds to the notion that testing for predictive validity is often an important yet under-developed element in social science research (Dubin, 1978). Specifically, we propose that firms’ life cycle stage will moderate the relationship between sequences types and performance. We find in our results that focused strategy periodic sequence and synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence show positive effects on performance controlling for other important factors. These results provide support for our proposition that sequence types do have an effect on performance, thus establishing predictive validity through validating the sequence variables with a particular criterion (Carimines & Zeller, 1979). However, a close examination of the contingency effect reveals a more complex picture. We find that life cycle stage has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence type and performance, indicating that firms in an established stage will have higher performance when adopting synchronized dual strategy periodic sequence type than firms following the same temporal sequence strategy in either emerging or developmental stages. We think that our tentative results demonstrate that sequence analysis has much to offer to the M&A and alliance field and should be a priority area for future research. 22 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION Adopting a temporal lens requires that we explicitly incorporate time theories, assumptions, constructs and methods into the phenomenon we study (e.g. M&A). One of our goals is to make a modest contribution to the M&A and alliance literature by demonstrating how a temporal lens allows us to conceptualize questions that complement and sometimes challenge conventional modes of thinking. For example, during presentations of our work, many scholars have challenged our suggestion that firms develop M&A rhythms or synchronize their M&A and alliance initiatives with competitors. Yet, unless one can demonstrate that the results are statistical artifacts, we provide evidence that some firms do use a temporal lens and there are important performance consequences to the type of rhythm, synchronization and sequence firms pursue. While we acknowledge a variety of theoretical and methodological limitations in our work, our results suggest that adopting a temporal lens is a rich and rewarding direction for M&A and alliance research. Below, we briefly explore some of our contributions as well as areas for future research. In examining the rhythm, synchronization and sequence of firms’ M&A and alliance initiatives, we placed time at the center stage of our both theoretical and empirical inquiry. This is consistent with strategy researchers’ call for an examination of time as an important issue on its own right rather than as part of the general background (Albert, 1995; Ancona et al., 2001), which limits our ability to fully realize the potential of a temporal lens in strategy field. Drawing on Mosakowski and Earley (2000), our conceptualization and methods assume the nature of time as real (has direct consequences on performance), objective, cyclical and discrete (time consists of equal and comparable units and a temporal reference point incorporating the past, present and future (Tobin’s Q)). While our approach is internally consistent, other approaches are equally viable. For example, research exploring a subjective view of time and international differences in managers’ temporal perspectives would provide valuable contributions to the M&A and alliance literature. The temporal constructs of rhythm, synchronization and sequence are characterized by complex forms of temporal repetition and as such differ significantly from temporal concepts such as speed or duration. These complex forms of repetition create unique challenges and opportunities for understanding the dynamics of building M&A and alliance portfolios. The current emphasis on studying multiple processes and multi-level phenomena A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 23 over time (Pettigrew, 1992; Powell, 1992; Van de Ven, 1992) requires theory and methods that accommodate complex interactions. In this respect, our research complements the focus on a single M&A or alliance in that we are interested in how and why the temporal pattern of a firm’s overall M&A and alliance history impacts its performance rather than how a single initiative impacts performance. In our theory, we described a few mechanisms which help explain our statistical findings. A fruitful area would be to identify and catalog a set of mechanisms (Hedstrom & Swedberg, 1998) that explain why and how firms develop rhythms, synchronization and sequences in their M&A and alliance initiatives. Theoretically, we suggest several theoretical lenses from other disciplines that can be leveraged to better understand M&A and alliance temporal patterns. The social entrainment model and the sociological view of sequence used in our studies have the potential to shed new light on a variety of important M&A and alliance questions. For instance, the sociological perspective provides theoretical underpins of why firms’ sequences of strategic initiatives along their trajectories or path do not occur in infinite combination and therefore can be empirically identified as gestalts (Miller & Friesen, 1980). The social entrainment model also allows researchers to incorporate temporal constructs in a systematic way and explore the rationale underlying the rhythmic behaviors of companies’ strategic initiatives. Alternatively, leveraging some of our strategy theoretical frameworks such as the resource-based view, the knowledge-based firm and industrial organization economics by integrating a temporal perspective, its associated constructs and relevant research questions would be valuable. Given the limited attention to a temporal lens, our ability to conduct evidence-based research in this emerging and rewarding field has been greatly restricted. The most exciting aspect of our core research question: ‘‘How and if the rhythm, synchronization and sequence of firms’ M&A and alliance activity over time impacts firm performance?’’, centers on the practicing manager. If our results are robust, managers have another tool, a temporal lens, as they conceptualize, build, negotiate, implement and restructure their M&A and alliance portfolios. The adoption of a temporal lens focusing on the rhythm, synchronization and sequence of M&A and alliance initiatives can help achieve corporate goals and possibly create another form of competitive advantage. Hopefully, we have stimulated some thought regarding how your firm can incorporate a temporal lens to complement your others lens. 24 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI NOTES 1. According to Collier (2007), ‘‘His (Tomlin’s) thoughtfully non-rhythmic remark was crafted to explain that (training) camp schedule is designed to make players uncomfortable and unable to anticipate any pattern to the tasks, the better to sharpen their cognition and adaptability y’’. In our context, we extend his meaning to reflect a desire to be semi-predictable not only to the players but also to the other teams and coaches in the NFL. 2. We thank George Lasezkay, a former Corporate Vice President, Business Development at Allergan, for identifying this rationale during our interview. 3. The distinction between ‘‘typology’’ and ‘‘taxonomy’’ is sometimes taken as the difference between conceptually derived and empirically derived schemes (Hambrick, 1983; Sneath & Sokal, 1973). The two words are often used interchangeably in the previous organizational literature (Hawes & Crittenden, 1984; Miles & Snow, 1978; Miller & Friesen, 1980; Slater & Olson, 2001). We used taxonomy to specifically refer to empirically derived classification schemes (Harrigan, 1985; Hawes & Crittenden, 1984; Slater & Olson, 2001). REFERENCES Abbott, A. (1995). Sequence analysis: New methods for old ideas. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 93–113. Abbott, A. (2000). Reply to Levine and Wu. Sociological Methods and Research, 29, 65–76. Abbott, A., & Hrycak, A. (1990). Measuring resemblance in sequence data: An optimal matching analysis of musicians’ careers. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 144–185. Albert, S. (1995). Towards a theory of timing: An archival study of timing decisions in the Persian Gulf War. Research in Organizational Behavior, 17, 1–70. Ancona, D. G., & Chong, C. (1996). Entrainment: Pace, cycle, and rhythm in organization behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 251–284. Ancona, D. G., Goodman, P. S., Lawrence, B. S., & Tushman, M. L. (2001). Time: A new research lens. Academy of Management Review, 26, 645–663. Audretsch, D. B. (1995). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 441–457. Barkema, H. G., Baum, J. A. C., & Mannix, E. A. (2002). Management challenges in a new time. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 916–930. Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120. Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1997). The art of continuous change: Linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 1–34. Butler, R. (1995). Time in organizations: Its experience, explanations and effects. Organization Studies, 16, 925–950. Carimines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 25 Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1986). On the structure and sequence of issue evolution. American Political Science Review, 80, 901–920. Carow, K., Heron, R., & Saxton, T. (2004). Do early birds get the returns? An empirical investigation of early-mover advantages in acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 25, 563–585. Carroll, G. R., & Hannan, M. T. (1990). Density delay in the evolution of organizational populations: A model and five empirical tests. In: J. V. Singh (Ed.), Organizational evolution (pp. 103–128). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Chand, S., & Chhajed, D. (1992). A single machine model for determination of optimal due dates and sequence. Operations Research, 40, 596–602. Collier, G. (2007, July 29). NFL coaching landscape inviting for Tomlin. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35, 1504–1513. Dubin, R. (1978). Theory building (revised ed.). New York, NY: Free Press. Edwards, L. (1927). The natural history of revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 543–576. Geibler, K. A. (2002). A culture of temporal diversity. Time & Society, 11, 131–140. Gisiner, R., & Schusterman, R. J. (1992). Sequence, syntax and semantics. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 106, 78–91. Goodwin, B. (1970). Biological stability. In: C. H. Waddington (Ed.), Toward a theoretical biology (Vol. 3, pp. 1–17). Chicago: Aldine. Grimm, C., & Smith, K. (1997). Strategy as action: Industry rivalry and coordination. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing. Gulati, R. (1995). Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 85–112. Haleblian, J., & Finkelstein, S. (1999). The influence of organizational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 29–56. Halpin, B., & Chan, T. (1998). Class careers as sequences: An optimal matching analysis of work-life histories. European Sociological Review, 14, 111–130. Hambrick, D. C. (1983). An empirical typology of mature industrial-product environments. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 213–230. Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 83–103. Han, S. K., & Moen, P. (1999). Clocking out: Temporal patterning of retirement. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 191–236. Harrigan, K. R. (1985). An application of clustering for strategic group analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 6, 55–73. Hawes, J. M., & Crittenden, W. F. (1984). A taxonomy of competitive retailing strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 275–287. Hedstrom, P. & Swedberg, R. (Eds). (1998). Social Mechanisms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Hoffmann, W. H. (2007). Strategies for managing a portfolio of alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 827–856. 26 JOHN E. PRESCOTT AND WEILEI (STONE) SHI Homburg, C., & Bucerius, M. (2006). Is speed of integration really a success factor of mergers and acquisitions? An analysis of the role of internal and external relatedness. Strategic Management Journal, 27, 347–367. Huy, Q. N. (2001). Time, temporal capability, and planned change. Academy of Management Review, 26, 601–623. Jansen, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. L. (2005). Marching to the beat of a different drummer: Examining the impact of pacing congruence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 93–105. Kale, P., Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (2002). Alliance capability, stock market response, and long-term alliance success: The role of the alliance function. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 747–767. Kogut, B. (1991). Joint ventures and the option to expand and acquire. Management Science, 37, 19–33. Koka, B. R., & Prescott, J. E. (2002). Strategic alliances as social capital: A multidimensional view. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 795–816. Krackhardt, D. (1990). Assessing the political landscape: Structure, cognition and power in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 342–369. Laamanen, T., & Keil, T. (2008). Performance of serial acquirers: An acquisition program perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 663–672. Lavie, D. (2007). Alliance portfolios and firm performance: A study of value creation and appropriation in the U.S. software industry. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1187–1212. Lesnard, L. (2004). Schedules as sequences: A new method to analyze the use of time based on collective rhythm with an application to the work arrangements of French dual-earner couples. Electronic International Journal of Time Use Research, 1, 63–88. Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York, NY: Knopf. Lieberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9(Summer special issue), 41–58. McGrath, J. E., & Kelly, J. R. (1986). Time and human interaction: Toward a social psychology of time. New York, NY: Guilford. Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1980). Archetypes of organizational transition. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 268–299. Mintzberg, H. (1990). The design school: Reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 171–195. Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. W. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate, and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272. Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2000). A selective review of time assumptions in strategy research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 796–812. Oatley, K., & Goodwin, B. C. (1971). The explanation and investigation of biological rhythms. In: W. P. Colquhoun (Ed.), Biological rhythms and human performance (pp. 1–38). New York, NY: Academic Press. Ofori-Dankwa, J., & Julian, S. D. (2001). Complexifying organizational theory: Illustrations using time research. Academy of Management Review, 26, 415–430. Pak, O. C., & Tennyson, R. D. (1986). Computer-based response-sensitive design strategies for selecting presentation form and sequence of examples in learning of coordinate concepts. Journal of Education Psychology, 78, 153–158. A Temporal Perspective of Corporate M&A and Alliance Portfolios 27 Pettigrew, A. M. (1992). The character and significance of strategy process research. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 5–16. Powell, T. C. (1992). Organizational alignment as competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 119–134. Rumelt, R. P., Schendel, D. E., & Teece, D. J. (1994). Fundamental issues in strategy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Slater, S. F., & Olson, E. M. (2001). Marketing’s contribution to the implementation of business strategy: An empirical analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1055–1067. Sneath, P. H. A., & Sokal, R. R. (1973). Numerical taxonomy. San Francisco: W.G. Freeman. Souza, G. G., Bayus, B. L., & Wagner, H. M. (2004). New-product strategy and industry clockspeed. Management Science, 50, 537–549. Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509–533. Tolstoy, P., & Deboer, W. R. (1989). An archeological sequence for the Santiago Cayapas River basin, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. Journal of Field Archeology, 16, 295–308. Van de Ven, A. H. (1992). Suggestions for studying strategy process: A research note. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 169–191. Vermeulen, F., & Barkema, H. (2002). Pace, rhythm, and scope: Process dependence in building a profitable multinational corporation. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 637–653. Volberda, H. W., & Lewin, A. Y. (2003). Guest editors’ introduction: Co-evolutionary dynamics within and between firms: From evolution to co-evolution. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 2111–2136. Zajac, E. J., Kraatz, M. S., & Bresser, R. K. F. (2000). Modeling the dynamics of strategic fit: A normative approach to strategic change. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 429–453.