Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 52 (2014) 185–189

Distal cervical caries in the mandibular second molar: an

indication for the prophylactic removal of third molar teeth?

Update

Louis W. McArdle a,∗ , Fraser McDonald b , Judith Jones c

a

b

c

Department of Oral Surgery, KCL Dental Institute, Guy’s & St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom

Department of Orthodontics, KCL Dental Institute, Guy’s & St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9RT, United Kingdom

Department of Oral Surgery, QMUL Dental Institute, The Royal London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Whitechapel, London E1 1BB, United Kingdom

Accepted 13 November 2013

Available online 7 December 2013

Abstract

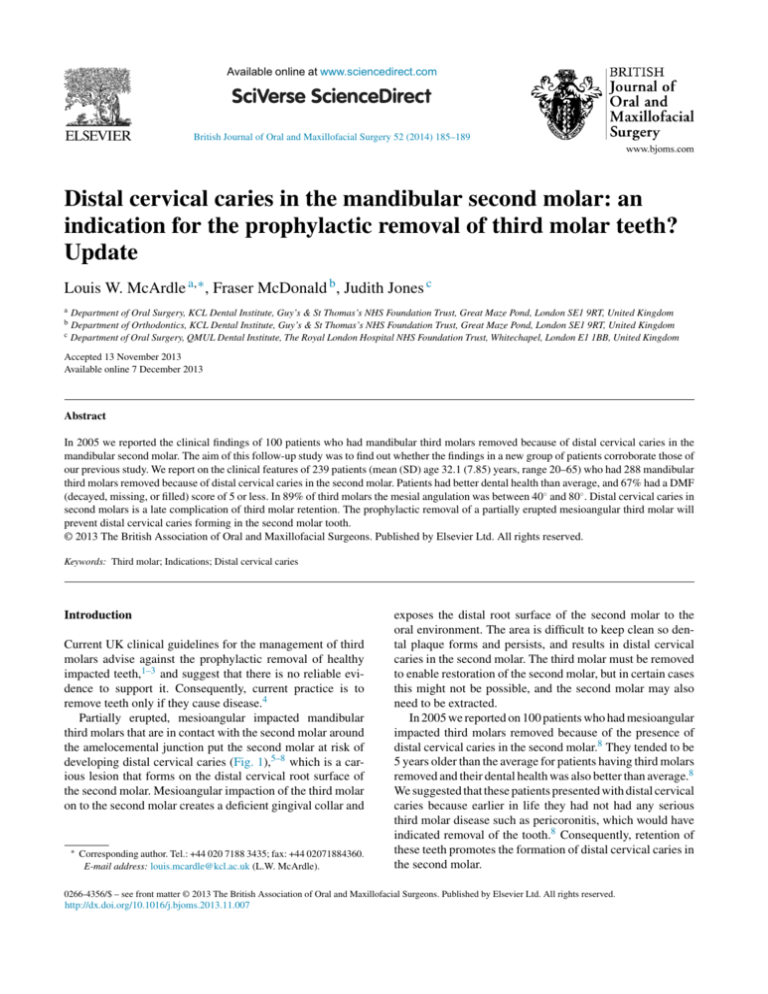

In 2005 we reported the clinical findings of 100 patients who had mandibular third molars removed because of distal cervical caries in the

mandibular second molar. The aim of this follow-up study was to find out whether the findings in a new group of patients corroborate those of

our previous study. We report on the clinical features of 239 patients (mean (SD) age 32.1 (7.85) years, range 20–65) who had 288 mandibular

third molars removed because of distal cervical caries in the second molar. Patients had better dental health than average, and 67% had a DMF

(decayed, missing, or filled) score of 5 or less. In 89% of third molars the mesial angulation was between 40◦ and 80◦ . Distal cervical caries in

second molars is a late complication of third molar retention. The prophylactic removal of a partially erupted mesioangular third molar will

prevent distal cervical caries forming in the second molar tooth.

© 2013 The British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Third molar; Indications; Distal cervical caries

Introduction

Current UK clinical guidelines for the management of third

molars advise against the prophylactic removal of healthy

impacted teeth,1–3 and suggest that there is no reliable evidence to support it. Consequently, current practice is to

remove teeth only if they cause disease.4

Partially erupted, mesioangular impacted mandibular

third molars that are in contact with the second molar around

the amelocemental junction put the second molar at risk of

developing distal cervical caries (Fig. 1),5–8 which is a carious lesion that forms on the distal cervical root surface of

the second molar. Mesioangular impaction of the third molar

on to the second molar creates a deficient gingival collar and

∗

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 020 7188 3435; fax: +44 02071884360.

E-mail address: louis.mcardle@kcl.ac.uk (L.W. McArdle).

exposes the distal root surface of the second molar to the

oral environment. The area is difficult to keep clean so dental plaque forms and persists, and results in distal cervical

caries in the second molar. The third molar must be removed

to enable restoration of the second molar, but in certain cases

this might not be possible, and the second molar may also

need to be extracted.

In 2005 we reported on 100 patients who had mesioangular

impacted third molars removed because of the presence of

distal cervical caries in the second molar.8 They tended to be

5 years older than the average for patients having third molars

removed and their dental health was also better than average.8

We suggested that these patients presented with distal cervical

caries because earlier in life they had not had any serious

third molar disease such as pericoronitis, which would have

indicated removal of the tooth.8 Consequently, retention of

these teeth promotes the formation of distal cervical caries in

the second molar.

0266-4356/$ – see front matter © 2013 The British Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.11.007

186

L.W. McArdle et al. / British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 52 (2014) 185–189

40

35

Percentage

30

25

20

15

10

5

Age range of patients (years)

Fig. 2. Age range of patients (years) compared with percentage number of

patients. Mean (SD) age 32.1 (7.85) years (range 20–65).

Fig. 1. Radiograph of distal cervical caries in the mandibular second molar

with associated impacted mesioangular third molar.

The aim of this follow-up study was to assess a further

group of patients with distal cervical caries in their mandibular second molars to find out if the findings corroborated those

of our 2005 study.

Methods

We evaluated 239 patients who had mandibular third molars

removed because of the presence of distal cervical caries in

the second molar. Data were prospectively collected over a

24-month period.

The variables that we recorded were sex, age, angulation

and eruption status of the third molar, DMF (decayed, missing, or filled) score, and the proximity of the third molar to

the amelocemental junction of the second molar.

As in our previous study, the DMF score was used as

a measure of dental health. In calculating the score we

compensated for, and excluded, the second molar if distal

cervical caries was the only lesion associated with the tooth.

The mesial angulation of the third molar was calculated by

measuring the angle of intersection between the mandibular occlusal plane and the occlusal plane of the third molar.

This angle equates to the mesial inclination of the third molar

relative to the second molar.8

All 288 teeth were partially erupted. Radiographic examination showed that all were in contact with, or close to, the

amelocemental junction of the second molar, and all were

mesioangularly impacted against the second molar. Mesial

angulations of the third molars were grouped accordingly:

255 (89%) had an angulation of between 40◦ and 80◦ ; in 28

(10%) it was less than 40◦ , and in 5 (1%) it was more than

80◦ .

Discussion

To our knowledge, distal cervical caries in the second molar

has not been reported without an associated mesioangular

third molar, and we have not observed it. Although caries

can form on the distal aspect of any tooth, distal cervical

caries is unique as it is seen at the amelocemental junction

and is, in effect, a variant of root surface caries. We think that

it would not develop without an associated impacted third

molar.

Concern has been raised that in some studies, radiographic

cervical burnout may have been misdiagnosed as distal cervical caries resulting in a higher reported incidence.9 In this

study, as in our previous study, patients whose radiographic

images suggested cervical burnout were excluded from the

study (Fig. 3).

A factor that is associated with the risk of distal cervical caries developing in the second molar is the angulation

of the third molar. This type of second molar caries is seen

Results

The study included 239 patients (142 men and 97 women).

In 190 patients, a single second molar was affected, and both

were affected in 49 (bilateral disease). In total, 288 mandibular third molars were extracted, 144 from each side.

The mean (SD) age of the patients was 32.1 (7.85) years

(range 20–65) (Fig. 2). A total of 161 patients (67%) had a

DMF score of 5 or less; 56 (23%) had a score of between 6

and 10, and 22 (9%) had a score of 11 or more. Of note, 50

patients (21%) had a compensated DMF score of zero as the

only lesion was the distal cervical caries associated with the

second molar tooth.

Fig. 3. Radiograph of radiographic distal cervical burnout potentially misinterpreted as distal cervical caries.

Mean DMF score

L.W. McArdle et al. / British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 52 (2014) 185–189

25

35

20

30

15

187

25

2012

10

20

mean age

(years)

ADHS 09

5

15

10

incidence (%)

of caries &

related disease

Age group (years)

5

Fig. 4. Mean DMF (decayed, missing or filled) score of patients having

third molars removed because of distal cervical caries (2012) (light blue)

compared with mean DMF score calculated from the Adult Dental Health

Survey 2009 (dark blue).15

primarily in association with mesioangular impacted third

molars and, as in other studies, we found that a mesial angulation of between 40◦ and 80◦ was common.8–14 Of the 288

third molars extracted, 255 (89%) were within this range.

Mesial angulations outwith this range and in some cases of

horizontal impaction have been associated with distal cervical caries in second molars, but it has not been seen in vertical

or disto-angular impactions.

Based on the 2009 Adult Dental Health Survey (ADHS),

the mean DMF score for patients with distal cervical caries

was less than half the mean score for similar age groups in the

general population (Fig. 4).15 This also corresponds to our

findings in 2005 which were based on the 1998 ADHS.8,16 It

supports our suggestion that patients with better dental health

are more likely to retain a partially erupted third molar later

into life, and when this is mesioangular, are at risk of distal cervical caries developing in the second molar.8 It also

contradicts the notion that susceptibility to distal cervical

caries in second molars is solely associated with an increased

susceptibility to dental caries.5–7

It is logical to assume that people with low DMF scores

have a good standard of oral hygiene and this includes the

coronal aspect of partially erupted third molar teeth. Good

oral hygiene minimises the likelihood of pericoronitis and

results in the long-term retention of such teeth, but in the

case of a mesioangular third molar and a second molar with

a distal cervical root exposed to the oral cavity, distal cervical caries is a potential outcome. It seems to develop in

older patients and this may be reflected in the protracted time

it takes for dental caries to form compared with the time

it takes for pericoronitis to develop after a third molar has

erupted.8,17

The mean age of patients in this study was 32.1 years

(range 20–65), which is comparable with the mean age

(32 years) for all patients who have third molars removed

in the UK.18,19 In our previous study patients with distal cervical caries tended to be 5 years older than average

whereas this study suggests that they are similar in age.19

This may be because in the UK, the introduction of third

molar guidelines by the National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE) and others has resulted in a shift

0

Year

Fig. 5. Increasing percentage incidence of caries and related disease (blue

line) as main indication for removal of third molars, and increase in mean

age of patients (orange line) having third molars removed.18,19

away from the prophylactic removal of third molars, primarily in younger patients, to removal based on definitive

clinical indications.1–4,19 The consequence of this has been an

increase in the mean age of patients from 28 to 32 years.18,19

The incidence of third molars being removed because of

caries and related sequelae such as periapical infection has

also increased from 4% to about 30% (Fig. 5).18,19 The mean

age in our group suggests a relation with an increased mean

age and a higher incidence of third molar caries in general,

as is the case with an increasing incidence of distal cervical

caries in older patients.17,19

It is not possible to isolate data from NHS agencies on

caries that solely affect the third molar or on distal cervical

caries of the second molar that is attributed to the third molar,

but the general trend of an increase in caries related to third

molars is noteworthy.18,19 Distal cervical caries in second

molars in association with impacted third molars is becoming

more widely reported, and is not isolated to any specific racial

group.10–14 Recent studies have reported an incidence of up

to 20% in patients having third molars assessed, and some

report an incidence of about 40% in mesioangular impacted

third molars.10,11

Older studies report a mean age of around 25 years for

patients having third molars removed, and report pericoronitis as the most common indication.20–24 As these studies

were published when the prophylactic removal of third

molars in younger patients was common, their mean age

was lower.20–24 The incidence of third molars being removed

because of caries in younger patients is relatively low, and

historically the reported incidence of distal cervical caries in

second molars in these patients has also been relatively low

(2–5%).8,17,19,20

As distal cervical caries is responsible for a rising percentage of third molars being removed we think that there is

a high risk of it developing in a second molar.10–14,17 However, pericoronitis is still the most common indication for

the removal of third molar teeth, and it is diagnosed more

often in younger patients.5,7,17,20,23,24 In these patients the

extraction of mandibular mesioangular third molars removes

188

L.W. McArdle et al. / British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 52 (2014) 185–189

the main contributing factor for distal cervical caries in the

second molar. If pericoronitis was less common in younger

patients then more third molar teeth would be retained later

into life. As a consequence, we suggest that the incidence

of distal cervical caries in the second molar will rise accordingly, as is the case with that of general caries that are related

to third molars in older patients.17–19

We need to consider whether all partially erupted mesioangular third molars would eventually cause distal cervical

caries in the second molar. A study of this latent potential

would require the enforced retention of a mesioangular third

molar to observe its effect on the adjacent tooth, but this

would be unethical and unavoidably protracted over many

years. The introduction of clinical guidelines such as NICE

has resulted in an older patient population whose third molars

are retained until specific problems indicate their removal. In

some respects the patient whose third molar is retained later

into life is acting as their own control to the long term consequences of retention as is demonstrated by the increasing

incidence of third molar caries (4-30%) correlating with the

increasing mean age of patients (Fig. 5).

The potential risk of distal cervical caries forming in second molar teeth that are associated with mesioangular third

molars presents a clinical dilemma: should the third molar

be left until disease develops, or should it be removed, and if

so, when? Clinical risk should influence the decision and the

relative risk – for example, of nerve damage, is an important

consideration. Early removal of a third molar with a high risk

of injury to the inferior dental nerve may not be prudent and

in such a case alternative options such as coronectomy could

be considered.

Conclusion

We do not think that all third molars should be removed prophylactically, but early, prophylactic removal of a partially

erupted mesioangular mandibular third molar will prevent

distal cervical caries forming in the adjacent tooth. Mesioangular third molars will not always cause distal cervical caries

to form as many will be removed because of pericoronitis and

other diseases before it ensues, but we do suggest that every

partially erupted mesioangular third molar has this potential. Only with further research and debate will we know

whether or not targeted prophylactic removal of such teeth

is acceptable. The cost–benefit and cost–effectiveness of this

are complex issues and are out of the sphere of this paper,

but prophylactic removal will be explored in further ongoing

research.

The results of our 2 studies and others confirm that distal cervical caries in the second molar is associated with the

retention of a partially erupted mesioangular third molar tooth

into later life.8,10–14 As this study corroborates our previous findings we suggest that the conservative management

of disease-free, partially erupted, mesioangular mandibular

third molars may be detrimental to dental health.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethics statement

Not required.

References

1. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the removal

of wisdom teeth. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/

pdf/wisdomteethguidance.pdf [March 2000].

2. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management unerupted

and impacted third molar teeth. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/

pdf/sign43.pdf [September 1999].

3. Prophylactic removal of third molars: is it justified? Effectiveness Matters, Vol. 3. University of York: NHS Centre for

Reviews and Dissemination; 1998. Available from: http://www.york.

ac.uk/inst/crd/EM/em32.pdf

4. Mettes TD, Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Perry J, van der Sanden WJ,

Plasschaert A. Surgical removal versus retention for the management

of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;6:CD003879.

5. van der Linden W, Cleaton-Jones P, Lownie M. Diseases and lesions

associated with third molars. Review of 1001 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995;79:142–5.

6. Current clinical practice and parameters of care: the management of patients with third molar (syn: wisdom) teeth. Faculty

of Dental Surgery of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Available from: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/publications-clinical[September

guidelines/clinical guidelines/documents/3rdmolar.pdf

1997].

7. Knutsson K, Brehmer B, Lysell L, Rohlin M. Pathoses associated with

mandibular third molars subjected to removal. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996;82:10–7.

8. McArdle LW, Renton TF. Distal cervical caries in the mandibular second

molar: an indication for the prophylactic removal of the third molar? Br

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;44:42–5.

9. Littler B. X-ray burn out. Br Dent J 2009;207:194.

10. Ozeç I, Hergüner Siso S, Taşdemir U, Ezirganli S, Göktolga G. Prevalence

and factors affecting the formation of second molar distal caries in a

Turkish population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;38:1279–82.

11. Chang SW, Shin SY, Kum KY, Hong J. Correlation study between distal

caries in the mandibular second molar and the eruption status of the

mandibular third molar in the Korean population. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;108:838–43.

12. Allen RT, Witherow H, Collyer J, Roper-Hall R, Nazir MA, Mathew

G. The mesioangular third molar—to extract or not to extract? Analysis

of 776 consecutive third molars. Br Dent J 2009;206:E23, discussion

586–7.

13. Falci SG, de Castro CR, Santos RC, et al. Association between the presence of a partially erupted mandibular third molar and the existence of

caries in the distal of the second molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2012;41:1270–4.

14. Oderinu OH, Adeyemo WL, Adeyemi MO, Nwathor O, Adeyemi

MF. Distal cervical caries in second molars associated with impacted

mandibular third molars: a case–control study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol Oral Radiol 2012. PMID: 22981096 [Epub ahead of print].

15. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Adult dental health survey.

London: HMSO; 2009. Available from: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statisticsand-data-collections/primary-care/dentistry/adult-dental-health-survey2009–summary-report-and-thematic-series [March 2011].

L.W. McArdle et al. / British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 52 (2014) 185–189

16. Office for National Statistics. Adult dental health survey (1998): oral

health in the United Kingdom, 1998. London: HMSO; 2000.

17. Bruce RA, Frederickson GC, Small GS. Age of patients and morbidity associated with mandibular third molar surgery. J Am Dent Assoc

1980;101:240–5.

18. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hospital episodes statistics.

HES online. Available from: www.hesonline.nhs.uk

19. McArdle LW, Renton T. The effects of NICE guidelines on the management of third molar teeth. Br Dent J 2012;213:E8.

20. Brickley MR, Shepherd JP. An investigation of the rationality of lower

third molar removal, based on USA National Institutes of Health criteria.

Br Dent J 1996;180:249–54.

189

21. Chiapasco M, De Cicco L, Marrone G. Side effects and complications

associated with third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

1993;76:412–20.

22. de Boer MP, Raghoebar GM, Stegenga B, Scheon PJ, Boering G. Complications after mandibular third molar extraction. Quintessence Int

1995;26:779–84.

23. Nordenram Å, Hultin M, Kjellman O, Ramström G. Indications for surgical removal of the mandibular third molar. Study of 2,630 cases. Swed

Dent J 1987;11:23–9.

24. Lysell L, Rohlin M. A study of indications used for removal of

the mandibular third molar. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988;17:

161–4.