Rainforest Raptors in the heart of Africa

advertisement

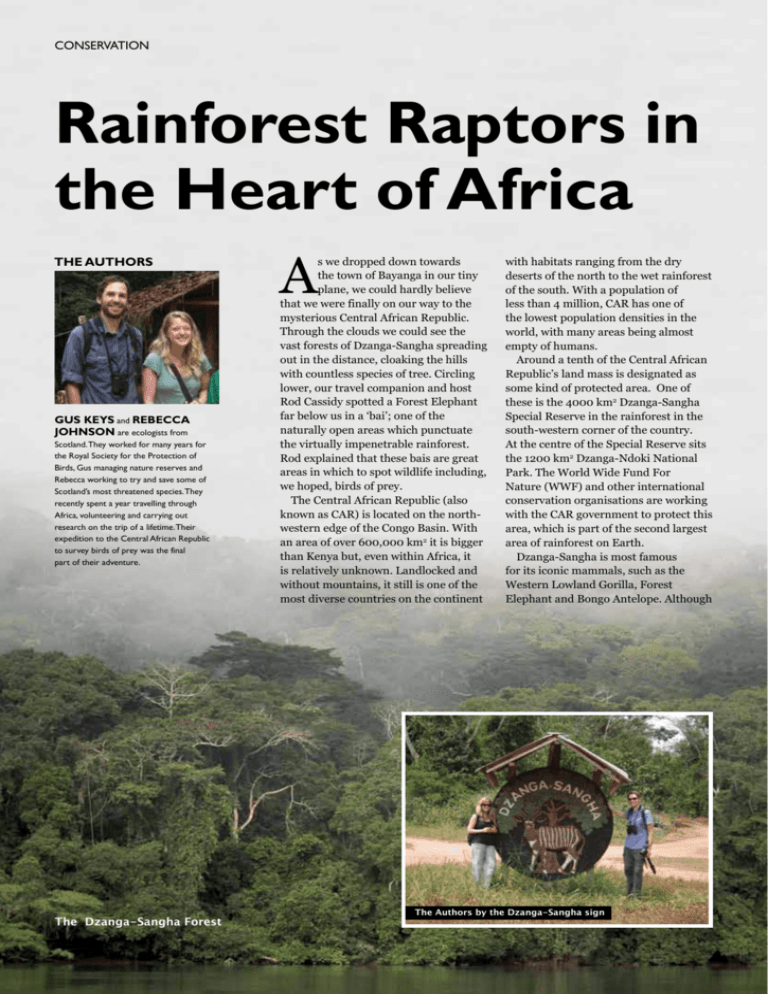

CONSERVATION Rainforest Raptors in the Heart of Africa THE AUTHORs Gus Keys and Rebecca Johnson are ecologists from Scotland. They worked for many years for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Gus managing nature reserves and Rebecca working to try and save some of Scotland’s most threatened species. They recently spent a year travelling through Africa, volunteering and carrying out research on the trip of a lifetime. Their expedition to the Central African Republic to survey birds of prey was the final part of their adventure. The Dzanga-Sangha Forest 32 SWARA JULY -SEPTEMBER 2012 A s we dropped down towards the town of Bayanga in our tiny plane, we could hardly believe that we were finally on our way to the mysterious Central African Republic. Through the clouds we could see the vast forests of Dzanga-Sangha spreading out in the distance, cloaking the hills with countless species of tree. Circling lower, our travel companion and host Rod Cassidy spotted a Forest Elephant far below us in a ‘bai’; one of the naturally open areas which punctuate the virtually impenetrable rainforest. Rod explained that these bais are great areas in which to spot wildlife including, we hoped, birds of prey. The Central African Republic (also known as CAR) is located on the northwestern edge of the Congo Basin. With an area of over 600,000 km2 it is bigger than Kenya but, even within Africa, it is relatively unknown. Landlocked and without mountains, it still is one of the most diverse countries on the continent with habitats ranging from the dry deserts of the north to the wet rainforest of the south. With a population of less than 4 million, CAR has one of the lowest population densities in the world, with many areas being almost empty of humans. Around a tenth of the Central African Republic’s land mass is designated as some kind of protected area. One of these is the 4000 km2 Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve in the rainforest in the south-western corner of the country. At the centre of the Special Reserve sits the 1200 km2 Dzanga-Ndoki National Park. The World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) and other international conservation organisations are working with the CAR government to protect this area, which is part of the second largest area of rainforest on Earth. Dzanga-Sangha is most famous for its iconic mammals, such as the Western Lowland Gorilla, Forest Elephant and Bongo Antelope. Although The Authors by the Dzanga-Sangha sign www.eawildlife.org CONSERVATION TOP LEFT: Gus scans for raptors along the river banks. BELOW LEFT: Bird survey skills training with students and trackers" TOP RIGHT: Harrier Hawk in flight. BELOW RIGHT: A 'bai', a naturally occurring open area in the rainforest. a large amount of research has been carried out on these species, very few formal studies have been made of the nearly 400 species of birds found in the Special Reserve. Dr Munir Virani, Africa Programmes Director with The Peregrine Fund, told us that he had been keen to undertake a raptor project in Dzanga-Sangha for many years, and when friend and fellow birder Rod Cassidy purchased Sangha Lodge in the heart of the Special Reserve in 2009, the idea became a reality. Fortunately for us, we were the lucky people who were getting to spend six weeks here in the heart of Africa, trying to gain an insight into some of the most under-studied bird species in the world. www.eawildlife.org The challenge that faced us was how to go about finding these often elusive forest-dwelling birds in their dense rainforest habitat. Most raptors are solitary and occupy large home ranges, and also tend to be shy of humans. Some species, such as Black Sparrowhawk and Congo Serpent Eagle, also spend much of their time perched motionless amongst the foliage, waiting to ambush their unsuspecting prey, making them even harder to see. To locate them, we walked slowly along a network of line transects, following small tracks and elephant trails through the forest, scanning the towering trees and dense understory for birds. We were entirely reliant on our excellent local BaAka guides, who amazed us with their ability to navigate the forest. The wide, winding Sangha River also turned out to be an excellent transect route, giving us a view of the forest edge where raptors are often more easily seen. Canoeing along the river in the early morning or late afternoon, watching Palm-nut Vultures soaring along the forested banks, is an experience that will not be quickly forgotten. The natural forest clearings, bais, like the one seen from the plane, did indeed turn out to be invaluable during our survey, providing us with breaks in the dense forest from which we could spot birds soaring above the canopy. The most impressive (and useful, with its SWARA JULY -SEPTEMBER 2012 33 CONSERVATION LEFT: Gus walks on one of the survey transects. MIDDLE: An impressive Western Lowland Gorilla silverback male. TOP RIGHT: A Fraser's Eagle Owl near Sangha Lodge. BOTTOM: Forest Elephants at Dzanga Bai 34 SWARA JULY -SEPTEMBER 2012 raised viewing platform) was Dzanga Bai, where in between raptor-spotting, we were treated to the daily sight of up to 100 Forest Elephants bathing in the mineral-rich mud. The area nearby also turned out to be a great spot for nocturnal raptors, such as Vermiculated Fishing Owl and Akun Eagle Owl. During the survey, we recorded 20 different species of raptor. By far the most common species was African Harrier Hawk Polyboroides typus, with a total of 71 separate records. Another seven species were reasonably common, with more than ten records each; Palm Nut Vulture Gypohierax angolensis, Black Kite Milvus migrans, Crowned Eagle Stephanoaetus coronatus, African Wood Owl Strix woodfordii, Cassin’s Hawk Eagle Aquila africana, Lizard Buzzard Kaupifalco monogrammicus, and Vermiculated Fishing Owl Scotopelia bouvieri. Less common species, with six or less records, were African Cuckoo Hawk Aviceda cuculoides, Bat Hawk Macheiramphus alcinus, African Goshawk Accipiter tachiro toussenelii, Fraser’s Eagle Owl Bubo poensis, Congo Serpent Eagle Dryotriorchis spectabilis batesi, Long-tailed Hawk Urotriorchis macrourus, and we had single sightings of African Fish Eagle Haliaeetus vocifer, Akun Eagle Owl Bubo leucostictus, Black Sparrowhawk Accipiter melanoleucus, Grey Kestrel Falco ardosiaceus, Red-chested Owlet Glaucidium tephronotum, and Sandy Scops Owl Otus icterorhynchus holerythrus. Unfortunately, we did not get sightings of either Chestnut-flanked Sparrowhawk Accipiter castanilius or Red-thighed Sparrowhawk Accipiter erythropus. Not surprising considering that Accipiter species are notoriously difficult to locate in tall, dense forest, due to their inconspicuous behaviour. It was striking to see the difference in the species composition when comparing the primary forest deep in Dzanga-Ndoki National Park with more disturbed forest habitats closer to www.eawildlife.org CONSERVATION The amazing team of BaAka trackers who made the survey possible. Gus interviews villagers about raptors with the help of Louis Sarno. human habitation. We spent a couple of invaluable weeks based at WWF’s remote Bai Hokou Forest Camp, just a few kilometres from the Congo border, where a dedicated team of researchers, volunteers, guides and BaAka trackers work with a habituated group of Western Lowland Gorillas. It was in this area that we were treated to our first views of Crowned Eagle, soaring and displaying majestically above the bais. It was also in this part of the www.eawildlife.org forest that we finally heard two of the most elusive species that we have been trying to track down, Congo Serpent Eagle and Long-tailed Hawk, both heard calling from amongst the dense understory. As well as finding different raptor species in this more remote area, we also saw many more raptors than in similar dense forest habitats close to areas of disturbance such as human habitation. This suggests a significant ‘edge effect’ is having an impact in Dzanga-Sangha, with raptors preferring more isolated forest areas, which means that increasing forest fragmentation is likely to have a detrimental effect on the number of raptors. A longer and more extensive survey would certainly provide more information on the make-up of the Dzanga-Sangha raptor community. There is so much to be learnt and further study would almost certainly uncover new and exciting knowledge. It is also vital in the long-term that more is learnt about the abundance, distribution and habitat requirements of tropical forest raptors, as most of the world's tropical rainforests are now heavily exploited. More knowledge can only help to inform decision-makers about the importance of DzangaSangha for birds of prey, and could aid its conservation in years to come. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to The Peregrine Fund for providing a grant to help conduct these studies under their Africa Programme, and in particular Dr Munir Virani, Africa Programmes Director, for endless assistance, enthusiasm, patience and friendship. Huge thanks to Rod Cassidy, his son Alon, and all the staff at Sangha Lodge; WWF staff in Bayanga and Bangui, particularly Anna Feistner and Angelique Todd; the Bai Hokou Forest Camp team, particularly Kathryn Shutt, Michael Stoerger and Barbora Kalousová; all the BaAka trackers in Dzanga-Sangha for using their incredible skills to help us find our way through the forest; and Andrea Turkalo and WCS staff at Dzanga Bai camp for kindly letting us use their camp as a base for part of our study. SWARA JULY -SEPTEMBER 2012 35