the right to work and basic income guarantees

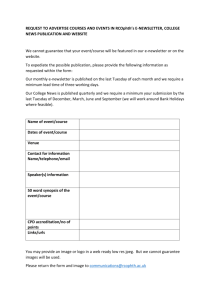

advertisement