2.4 Data & Graphs - Computer Graphics Home

advertisement

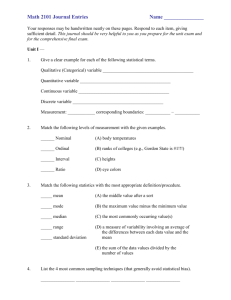

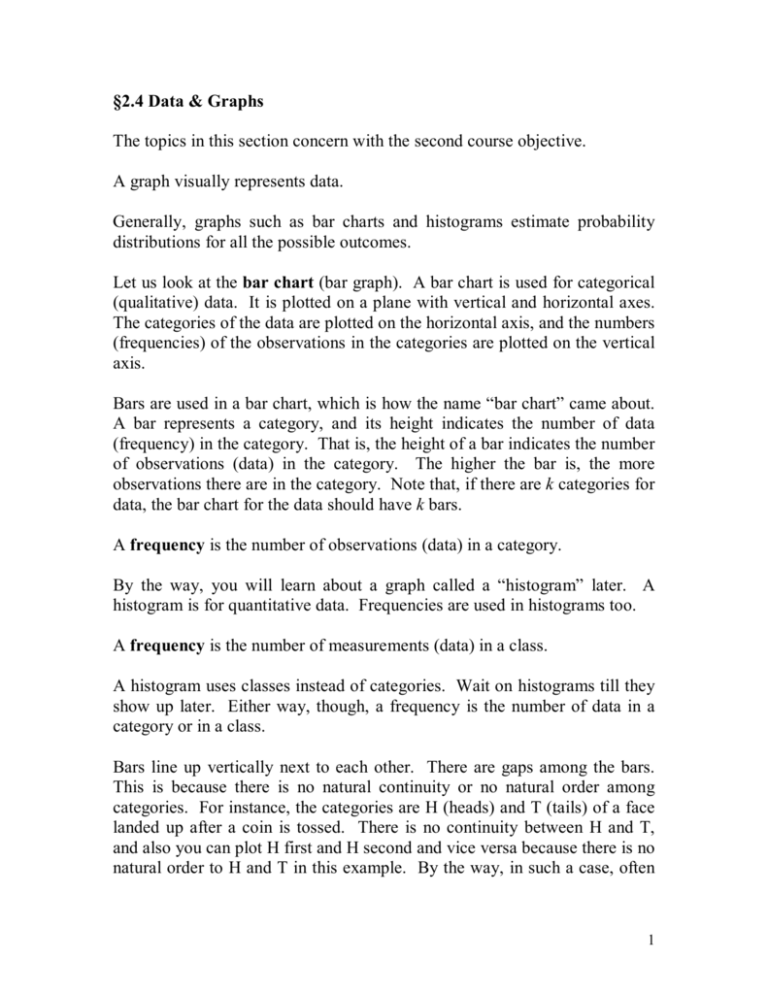

§2.4 Data & Graphs

The topics in this section concern with the second course objective.

A graph visually represents data.

Generally, graphs such as bar charts and histograms estimate probability

distributions for all the possible outcomes.

Let us look at the bar chart (bar graph). A bar chart is used for categorical

(qualitative) data. It is plotted on a plane with vertical and horizontal axes.

The categories of the data are plotted on the horizontal axis, and the numbers

(frequencies) of the observations in the categories are plotted on the vertical

axis.

Bars are used in a bar chart, which is how the name “bar chart” came about.

A bar represents a category, and its height indicates the number of data

(frequency) in the category. That is, the height of a bar indicates the number

of observations (data) in the category. The higher the bar is, the more

observations there are in the category. Note that, if there are k categories for

data, the bar chart for the data should have k bars.

A frequency is the number of observations (data) in a category.

By the way, you will learn about a graph called a “histogram” later. A

histogram is for quantitative data. Frequencies are used in histograms too.

A frequency is the number of measurements (data) in a class.

A histogram uses classes instead of categories. Wait on histograms till they

show up later. Either way, though, a frequency is the number of data in a

category or in a class.

Bars line up vertically next to each other. There are gaps among the bars.

This is because there is no natural continuity or no natural order among

categories. For instance, the categories are H (heads) and T (tails) of a face

landed up after a coin is tossed. There is no continuity between H and T,

and also you can plot H first and H second and vice versa because there is no

natural order to H and T in this example. By the way, in such a case, often

1

the bars of H and T are given in that order due to the alphabetical order of

the letters H and T.

For example, the following data and their bar chart are obtained from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bar_chart

Group Seats (2004)

EUL

39

PES

200

EFA

42

EDD

15

ELDR 67

EPP

276

UEN

27

Other 66

A bar chart visualizing the above results of the 2004 election can look like

the bar chart given below.

2

By the way, if all the values were arranged in descending order this type of

bar graph would be called a Pareto chart.

Let us have an example with data of size 100. Suppose there are 34 H’s and

66 T’s. Then, you get a bar chart consisting of two bars; one bar whose

height is 34 for the category H and another bar whose height is 66 for the

category T. See the bar chart below. You can put the bar for H first and that

for T second (from left to right) or the bar for T first and that for H second.

Either way, this bar chart estimates the probability distribution for the

outcomes, H and T. The bar for T is about twice as high as that for H, which

means the bar chart estimates the probability distribution to be two to one for

T and H respectively. The bar chart below was generated by Excel.

3

You can use 0 for H and 1 for T. Still, there is no natural continuity and

order between the categories 0 and 1 since H can be numbered 7 and T can

be numbered -5. However, it might be a good practice to plot the bar with

small number (for a category) first, the bar with the second smallest number

(for a category) second and so on along the horizontal axis from left to right

since it is consistent with a real number line. It is also a good practice to

plot categories in the alphabetical order from left to right on the horizontal

axis if letters are used for categories.

When you plot data of ordinal scale in a bar chart, it is a little bit difference

in that there is a natural order among the categories. There is still no natural

continuity so bars are separate. However, the bars should be plotted in the

descending order or ascending order of the amount of the property. So, if

possible, it is a good practice to assign numbers or letters to the categories in

sequence as the amount of property increases or decreases (which is the

standard practice, anyway). This way, when bars are plotted by the

alphabetical or numerical order along the horizontal axis, the categories are

also given in the ascending or descending order of the amount of the

property.

4

There is a graph obtained from the bar chart. A Pareto chart is obtained

from a bar chart by rearranging the bars from the highest to the lowest from

left to right. Namely,

a Pareto chart is a bar chart whose bars are rearranged from the highest to

the lowest.

Given below is a Pareto chart of the coin toss example obtained from the bar

chart above. Note that the bar for T’s is given before the bar for H’s in the

Pareto chart because the bar for T’s is higher than the bar for H’s.

100 Coin Tosses

70

60

Number of H's & T's

50

40

Series1

30

20

10

0

T

H

Face Landed Up

The most frequent categories tend to be the most important category.

Generally, outcomes with higher probabilities are more important than those

with low probabilities. A high probability for an outcome results in more

frequent data of the outcome or category. This Pareto chart draws your

attention to the most frequent and important category by plotting its bar first

from the left. See the Pareto chart given below.

5

This Pareto chart is found at

http://www.hanford.gov/safety/vpp/pareto.htm

Pareto charts are frequently used in statistical quality control. For instance,

the categories are different causes for defects of products. Defective

products cost the company a great deal since they cannot be sold or have to

be reworked to be sold. So, consequently, the company wants to eliminate

(reduce) defective products. To do so, it needs to eliminate the causes for

defects. In the last month, say, Cause A caused 80 defective products, Cause

B caused 160 defective products, and Cause C caused 30 defective products.

Then, the company should go after Cause B first, certainly not Cause C first.

See the Pareto chart (generated by Excel) given below.

6

Pareto Chart for Defects by Causes

180

160

140

Number of Defects

120

100

Series1

80

60

40

20

0

Cause B

Cause A

Cause C

Cause

It would be ideal to go after all three causes, but a company often does not

have enough resources to do so. Also, even if it did, it would be better to go

after the cause that is causing the most defective products first with all the

resources available. A Pareto chart can indicate you that the first one (from

the left) is the one that the company should go after if it goes after only one

cause at a time.

A Pareto chart has bars just like a bar chart. These bars represent and

indicate exactly the same things that those in a bar chart represent. The bars

in a Pareto chart have gaps among them. However, Pareto chart always has

the highest bar to the lowest bar from left to right. By the way, the name

came from an Italian economist and sociologist, Vilfredo Pareto, who used

the chart first (at least, publicly). For Vilfredo Pareto, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vilfredo_Pareto

For bar charts and Pareto charts, the heights of bars can be relative

frequencies of data in the categories, instead of numbers (frequencies) of

data in the categories. The height of a bar indicates its relative frequency

(often, a decimal number or percentage) of data in the category. That is, the

7

height of a bar is the relative frequency (probability) per category.

relative frequency of a category is computed as

A

relative frequency = (the number of data in the category or class)/n

and also

relative frequency in % (or percentage relative frequency) =

(the number of data in the category or class)/n*100

where n is the sample size (the total number of measurements or

observations in the entire data). Note that the percentage (percent) relative

frequency is 100*(relative frequency).

For instance, the relative frequency for H in the coin toss example is

34/100 = 0.34

or

34/100*100 = 34%.

The relative frequency for T in the example is

66/100 = 0.66

or

66/100*100 = 66%.

The bar chart of the coin toss example with relative frequency is given

below (generated by Excel). As you can see, it looks very similar to the

earlier bar chart with the regular frequencies. In fact, they give pretty much

the same information (estimation) about the probability distribution of the

outcomes, H and T.

8

100 Coin Tosses

0.7

0.6

Relative Frequency

0.5

0.4

Series1

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

H

T

Face Landed Up

The relative frequency for Cause B in the cause-defects example is

160/270 = 0.593

or

160/270*100 = 59.3%.

The relative frequency for Cause A in the example is

80/270 = 0.296

or

80/270*100 = 29.6%.

The relative frequency for Cause C in the example is

30/270 = 0.111

9

or

30/270*100 = 11.1%.

A Pareto chart for the cause-defect data with percent relative frequencies is

given below (generated by Excel). Again, as you can see, it looks very

similar to the Pareto chart with the regular frequencies. They give pretty

much the same information (estimation) about the probability distribution of

the outcomes (causes).

Pareto Chart with Percet Relative Frequency

70

60

Percent Relative Frequency

50

40

Series1

30

20

10

0

Cause B

Cause A

Cause C

Cause

The highest bar in frequency is the highest bar in relative frequency (which

is true in percentage or not), and the lowest bar in frequency is the lowest

bar in relative frequency (which is true in percentage or not). That is, the

relative heights of bars are the same with frequencies or relative frequencies

(which is true in percentage or not) for the same data and give the same

estimation of the probability distribution for the outcomes.

Many statisticians prefer the relative frequencies to the frequencies because

a bar chart or Pareto chart estimates a distribution of probabilities which are

10

number between zero and one (0% and 100%) and so are the relative

frequencies.

There is another graph which estimates the distribution of probabilities for

outcomes from categorical data. It is a pie chart. It is called a pie chart

because it is circular and is sliced up like a pie. A student of mine called it a

pizza chart by mistake since it looks like a pizza as well.

A pie chart consists of slices or wedges completing a circle. Each slice

represents a category. So, if data have four categories, then their pie chart

should consist of four slices. The size of a slice indicates the relative

frequency of data in the categories while the size of a slice is determined by

the central angle of the slice. The central angle of the slice is computed as

(The number of data in the category)/n*360.

That is, a central angle is the relative frequency (not in percentage) times

360 degrees. The 360 degrees comes from the complete circle. Anyway,

the more data there are in a category, the bigger the slice for the category is.

With the coin toss example, there should be two slices in the pie chart. The

central angle (size) of the slice for H is computed as

34/100*360 = 122.4 degrees

and that of the slice for T is computed as

66/100*360 = 237.6 degrees.

Given below is the pie chart (generated by Excel) for the coin toss example.

11

100 Coin Tosses

T

H

In the cause-defect example, there should be three slices in the pie chart.

The central angle (size) of the slice for Cause B is computed as

160/270*360 = 213.3 degrees,

that of the slice for Cause A is computed as

80/270*360 = 106.7 degrees,

and

that of the slice for Cause C is computed as

30/270*360 = 40.0 degrees

Given below is the pie chart (generated by Excel) of the cause-defect

example.

12

Defects by Causes

Cause B

Cause A

Cause C

It is a good idea to check whether or not all the central angles add up to 360

degrees. If not, then you do not have a pie chart because a pie chart must be

a perfect (complete) circle which has exactly 360 degrees.

It is a good practice to start with a largest slice at 12 o’clock, the second

largest slice, and so on clockwise, like those pie charts given above.

However, you find many pie charts that do not follow this practice.

A pie chart estimates the probability distribution for all the outcomes like a

bar charts, but it is not as easy to use it for the purpose since the sizes of

slices are more difficult to compare one with other than the heights of bars

while a pie chart is a cute graph.

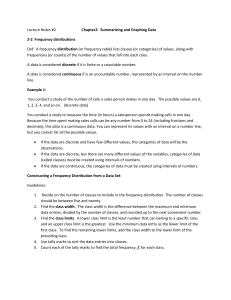

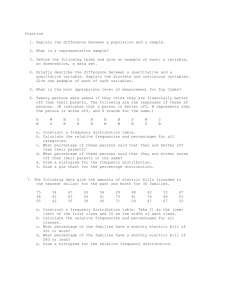

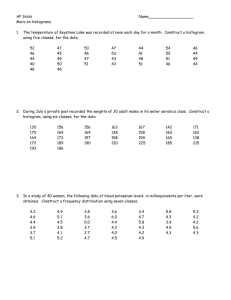

A histogram is used to represent non-categorical (quantitative) data such as

measurements. Non-categorical data have no category. Furthermore,

measurements are continuous real numbers (often, non-negative real

numbers but still are continuous). Thus, it is necessary to create categories

by grouping real numbers (measurements) into, somewhat, artificial

‘categories’ which are called classes (or bins). These classes are intervals

and they are continuous intervals. These intervals are called the first class,

13

the second class and so on from left to right (along the real number line, of

course).

Each class is indicated by its interval limits which are called class

boundaries. The upper and lower interval limits are called the upper and

lower class boundaries. The class mark of a class is the middle point

(midpoint) of the class. That is, the class mark of a class is computed as

(the upper class boundary + the lower class boundary)/2,

where these upper and lower class boundaries are those of the same class.

The distance between the upper and the lower class boundaries of a class is

called the class interval. That is, the length of an interval is called the class

interval and it is computed as

the upper class boundary – the lower class boundary,

where the upper and the lower class boundaries are those of the same class.

It is strongly recommended to use the same class interval for all the classes

in a histogram if possible.

The number of classes depends on the sample size; anywhere from 4 for

small data to 20 for huge data. If you create too many classes for data, you

end up with a bunch of classes with 0 or only 1 measurement in each of

them. If you create too few classes, you end up with a few classes with tall

bars. Avoid these situations since they do not estimate the probability

distribution well.

No empty classes are allowed at the ends; that is, the first and last classes

cannot be empty; while empty classes between the first and last classes are

allowed. Also, open classes can be used for the first class (open below – no

lower boundary) and the last class (open above – no upper boundary).

However, it is not a good practice.

Every measurement in data must be counted once and only once. That is,

the minimum measurement must be counted in the first class and the

maximum measurement must be counted in the last class. Also, no gaps

among the classes are allowed, which is different from the bar chart whose

bars (categories) have gaps among them. Like in bar charts, bars are used to

14

represent classes, and their heights indicate the numbers (frequencies) of

measurements in their classes. The heights of bars can be relative

frequencies (decimal numbers or percentages) as well.

A histogram is for non-categorical data which are measurements. They are

real numbers and (at least, theoretically) continuous and ordered. That is,

you cannot switch the classes around; they must be lined up consistently

with the real number line. After all, bottoms of classes (boxes) form

intervals for real numbers along the horizontal line. All the boundaries must

be in the ascending order from left to right, like the numbers on the real

number line.

The upper class boundary of one class and the lower class boundary of the

next class must be the same since no gap between two consecutive classes is

allowed. Otherwise, there could be a measurement which is not counted in

any class. Now, a problem of having coinciding upper and lower class

boundaries for two consecutive classes is how to determine in which class a

measurement whose value is identical to these boundaries should be

counted. It cannot be counted in both classes. To avoid this problem, class

boundaries come in one extra digit, to those digits in the measurements, at

the end. The extra digit is always 5. That is, if a number does not finish

with a digit 5, then it is not a class boundary.

Let us have an example of a histogram with the following data of size 12.

{{20.3, 16.3, 14.4, 9.2, 18.3, 22.9, 15.8, 17.4, 10.3, 19.2, 22.5, 12.8}}

These are Histogram Example Data. The sample size is small so I decide to

have only four classes.

The minimum and maximum measurements are 9.2 and 22.9 respectively.

So, the class interval should be close to

(22.9 – 9.2)/4 = 3.425.

In order not to leave any measurements outside of the first and last classes, I

choose the class interval to be 3.5. The minimum measurement is 9.2 so I

set the lower class boundary of the first class to be 9.15. Note that all the

measurements have the same precision of one place after the decimal point

and that the lower boundary has two places after the decimal, with one extra

15

digit of 5. The upper class boundary of the first class is 12.65 (= 9.15 + 3.5)

which is the lower class boundary of the second class. The upper class

boundary of the second class is, then, 16.15 (= 12.65 + 3.5) which is the

lower class boundary of the third class. The upper class boundary of the

third class is 19.65 (= 16.15 + 3.5) which is the lower class boundary of the

fourth (last) class. The upper class boundary is 23.15 (= 19.65 + 3.5). Note

that the last class contains the maximum measurement of 22.9 as should.

Now, I count the measurements in each class. As I go through the data, I

count the first measurement, 20.3, one for the fourth class, the second

measurement, 16.3, one for the third class, the third measurement, 14.4, one

for the second class, the fourth measurement, 9.2, one of the first class, the

fifth measurement, 18.3, two for the fourth class, the sixth measurement,

22.9, three for the fourth class, the seventh measurement, 15.8, two for the

second class, and so on. The summary is given in the following table.

CLASS

9.15-12.65

12.65-16.15

16.15-19.65

19.65-23.15

MEASUREMENT FREQUENCY

9.2, 10.3

2

12.8, 14.4, 15.8

3

16.3, 17.4, 18.3. 19.2

4

20.3, 22.5, 22.9

3

Total

12

The frequency is the number of measurements in each class (per class) and is

plotted on the vertical axis, and the classes are plotted on the horizontal axis

side by side without gaps. Bars are used to represents classes. So, in the

histogram for the data, there are four bars representing those four classes.

See the histogram given below.

16

The histogram of data,

{{20.3, 16.3, 14.4, 9.2, 18.3, 22.9, 15.8, 17.4, 10.3, 19.2, 22.5, 12.8}}

4

3

2

9.15

12.65

16.15

19.65

23.15

The first bar on the horizontal axis (real number line) is the bar for the first

class and it has the height of 2 (0.17 or 17% if the relative frequency were

used). The bottom of the bar is from 9.15 to 12.65 on the horizontal line.

The second bar has the height of 3 (0.25 or 25%), and its bottom is from

12.65 to 16.15 on the horizontal line. There is no gap between the first and

the second bars (different from bar charts). The third bar has the height of 4

(0.33 or 33%), and its bottom is from 16.15 to 19.65 on the horizontal line.

Again, there is no gap between the second and third bars. The fourth bar has

the height of 3 (0.25 or 25%), and its bottom is from 19.65 to 23.15 on the

horizontal line with no gap between this bar and the third bar.

A table such as the one given above is called a frequency table. A

frequency table must consist of at least two columns, one for classes (or

categories) and another one for their frequencies or relative frequencies.

The table given above actually has three columns; the middle column is the

extra column (for measurements or observations) which is optional for a

frequency table. A frequency table is used, as a middle step, for

constructing a histogram, a bar chart, a Pareto chart, a frequency polygon, or

such graph. It is also used to summarize data (by grouping) and present

them as grouped (processed) data.

17

Data are actually measured or observed outcomes of the interested property.

A probability distribution describes the distribution of probabilities for the

possible outcomes. This histogram estimates the probability distribution for

the outcomes. It estimates that, if another measurement is taken, the chance

of the measurement being between 16.15 and 19.65 is at 33%, the chance of

the measurement between 12.65 and 16.15 is the same as between 19.65 and

23.15 at 25%, and the chance of the measurement between 9.15 and 12.65 is

only 17%.

The real probability distribution might be a little bit different from the

histogram but should be similar or close to the histogram. If more data are

taken, and a histogram is constructed with more data and classes, then the

histogram would estimate the probability distribution better: that is, closer.

A histogram is used for non-categorical (quantitative) data while a bar chart

is used for categorical (qualitative) data. Non-categorical data come from

non-categorical outcomes, and a probability distribution for non-categorical

outcomes is different from the probability distribution for categorical

outcomes from which categorical data come from. For this, read Appendix:

Discrete and Continuous Probability Distributions given below.

Lines can be used in a graph instead of bars. For instance, in a histogram, a

class and its (relative) frequency can be indicated by a point as, (class mark,

frequency). Note that italicized letters are used to indicate that it is a point.

All these points are connected by straight lines. In fact, these lines estimate

the probability distribution better than bars. This is a reason why many

statisticians prefer frequency polygons to histograms.

A frequency polygon is a histogram with lines, instead of bars, connecting

points (class mark, frequency)‘s for all classes and one empty class on each

end.

A frequency polygon is not used in the place of a bar chart since connected

lines would falsely imply continuity and order among categories. The lower

and upper class boundaries specify a class in a histogram, but a class mark

specifies a class in a frequency polygon. Also, for a histogram, no empty

class is allowed on the end of either side. However, in a frequency polygon,

an empty class of the same class interval (class length) is added to the first

and last classes so that lines start from the horizontal axis and end on the

horizontal axis. That is, the lines start at the class mark of the first empty

18

class, (the first empty class mark, 0), and end at the class mark of the last

empty class, (the last empty class mark, 0).

See the frequency polygon given below.

This frequency polygon is found at http://cnx.org/content/m10214/latest/

You see (35, 0) for the first empty class and (155, 0) for the last empty class.

These are points on the horizontal axis and start from and end at the

horizontal axis (horizontal line) for the test scores.

It is called a frequency polygon since frequencies or relative frequencies are

plotted on the vertical line. With these two empty classes at the ends, the

lines connect with the horizontal axis. That is, the lines and the part of the

horizontal axis (a line) form a closed two-dimensional figure bounded by

straight lines. Such a geometric figure is a polygon. Now, you know the

reason why it is called a frequency polygon. If you understand it, you do not

have to memorize even its name.

Any graph that uses connected lines on a plane defined by the horizontal and

vertical axes is generally called a line graph. What is plotted on the vertical

line does not have to be frequencies, and lines do not have to start from and

end at the horizontal axis. However, if a line graph satisfies these two

conditions, it must be called a frequency polygon.

A line graph is any graph that represents data with connected lines on a

plane defined by the horizontal and vertical axes.

19

Such a graph is called a line graph because lines are used in the graph. By

the way, in Statistics like in mathematics, a line means a straight line. See

the line graph given below.

This line graph is found at

http://www.mathleague.com/help/data/IMG00002.gif

If time is sequentially plotted on the horizontal axis, a line graph is called a

time-series.

A time-series is a line graph with time sequentially plotted on the horizontal

axis.

For time-series, data must be taken sequentially in time, and the time

information must come with the data. For instance, the daily closing price of

a stock was taken over 30 business days. These 30 data consist of the 30

closing prices of the stock and they come with the information of days;

namely, which price is the closing price of which day. The time-series is

very useful in business and economics. See the time-series of economic data

given below.

20

History of the Dow Jones Industrial Average

1900-2006

This graph is a time-series since the horizontal axis is time (years) in the

natural sequence. On the other hand, the second last graph of the car’s value

is a line graph but not a time-series since the horizontal axis is the mileage

and not time. By the way, this time-series, History of Dow Jones Industrial

Average, is found at

http://www.analyzeindices.com/dow-jones-history.shtml

In a time-series, the points connected by lines are arranged in sequence (in

order) of time and, hence, it is called a time-series. Why do you have to

memorize this if you understand it?

A graph which represents data using diagrams and pictures but cannot be

categorized as any specific graph commonly used is called a pictograph (or

sometimes, a pictogram). For instance, a bar chart given horizontally (that

is, bars are given horizontally, not vertically) is a pictograph since, for a bar

chart, the bars must be given vertically. You find many pictographs in, for

instance, the USATODAY (check out its USA TODAY Snapshot).

Given below is an example of a pictograph found at

http://www.health.state.pa.us/hpa/stats/techassist/piechart.htm

21

This graph uses pictures to represent data but cannot be classified as a

specific graph that we have discussed. Thus, it is a pictograph.

Charts, diagrams and graphs (even tables) are very useful tools to make your

points and convince others with your point of view. It is very powerful

because, as Confucius said, “Seeing is believing.” With charts and graphs,

you could even convince voters to vote you into the highest office in this

country even if you were a short person with big ears and a bad haircut.

Florence Nightingale is known as the founding mother of the modern

nursing. She was also the founding mother of modern hospitals. Before her,

hospitals were death traps for patients. Patients used to die, in a great

proportion in hospitals, of contagious diseases and complications due to the

unsanitary conditions in hospitals.

Nightingale convinced the British government, using statistics with charts

and graphs, to spend more funds for her (originally, military) hospitals.

Basically, she showed the correlation between sanitary procedures and the

decline in unnecessary deaths in hospitals. For this, she started the practice

of keeping records (data) on patients in hospitals as well.

Nightingale came up with several graphs of her own. One of them is the

polar area diagram. In fact, she was a statistician too. Florence Nightingale

22

was a statistician?! Yes, she was. She was, indeed, the first female fellow

of the Royal Statistical Society. Please read Appendix (optional):

Florence Nightingale Nurse/Statistician given below.

Generally, graphs and charts are very abuseful (I made up this word) since

they are very powerful. Also, information from data can be easily distorted

with them. It is partially due to the optical illusion, but there is more to it.

So, be careful when someone tries to convince you with charts and graphs

for something; especially when the person has some kind of agenda, like

selling something.

Finally, please read Appendix: More about Charts and Graphs given at

the end of this section.

Appendix: Discrete and Continuous Probability Distributions

The probabilities for categorical outcomes (categories) come separately and

individually as bars in the bar chart. In a probability distribution for

categorical outcomes, each probability (weight) is located on every outcome.

Thus, the probability distribution for discrete outcomes such as categorical

outcomes is called a discrete probability distribution.

A discrete probability distribution is a probability distribution with

separate probabilities for discrete outcomes.

Categorical data come from a discrete probability distribution with

categorical outcomes.

Non-categorical outcomes are mostly measurements which are real numbers

and, at least theoretically, continuous and not discrete. So, the probabilities

for these continuous outcomes come continuously like connected and

continuous bars in a histogram. Thus, the probability distribution for noncategorical outcomes is called a continuous probability distribution. If you

shave the corners of the tops of bars in a histogram and make the tops sooth

continuous curves (instead of steps), it looks like a continuous probability

distribution.

A continuous probability distribution is a probability distribution with

continuous probabilities for continuous outcomes.

23

Non-categorical data come from a continuous probability distribution with

non-categorical outcomes.

The area of a bar in a bar chart and histogram is essentially a probability.

Suppose relative frequencies are used instead of frequencies (numbers of

measurements or observations). In a bar chart, a relative frequency is a

relative frequency per category; namely, a relative frequency of one

category. So, by using one for the base of a bar, the area of a bar is

computed by using the formula, the height times the base, as

a relative frequency/1*1 = a relative frequency

which is a probability for the category. This is a reason why many

statisticians prefer using relative frequencies (probabilities), instead of

frequencies (number of data), on the vertical axis and one for the base of a

bar for the bar chart.

For a histogram, the height of a bar is a frequency, number of measurements,

per class or a relative frequency per class. More specifically, the number of

measurements is counted in one class interval so the height of a bar is

actually (relative frequency)/(class interval). Now, the base of a bar is class

interval so the area of a bar is

(a relative frequency)/(class interval)*(class interval) = a relative frequency

which is a probability for the class. This is a reason why many statisticians

prefer using relative frequencies (probabilities), instead of frequencies

(number of data), on the vertical axis for the histogram. Nevertheless, the

relative sizes of areas of bars indicate the relative sizes of probabilities for

categories or classes.

24

Appendix (optional) : Florence Nightingale Nurse/Statistician

Florence Nightingale

Born: 12 May 1820 in Florence, Italy

Died: 13 August 1910 in East Wellow, England

Named after the city of her birth, Florence Nightingale was born at the Villa

Colombia in Florence, Italy, on May 12, 1820. Her elder sister had been born in

Naples the year before, and was named for the Greek city Parthenope.

The early education of Parthenope and Florence was placed in the hands of

governesses, but, later, their Cambridge educated father took over the

responsibility himself. Nightingale loved her lessons and had a natural ability for

studying. Under her father's influence, she became acquainted with the classics,

Euclid, Aristotle, the Bible, and political matters. In 1840, Nightingale begged her

parents to let her study mathematics, but her mother did not approve of this idea.

Although William Nightingale loved mathematics and had bequeathed this love to

his daughter, he urged her to study subjects more appropriate for a woman. After

many long emotional battles, Nightingale's parents finally gave their permission

and allowed her to be tutored in mathematics.

Nightingale developed an interest in the social issues of the time, but in 1845 her

family was firmly against the suggestion of her gaining any hospital experience.

Until then, the only nursing that she had done was looking after sick friends and

relatives. During the mid-nineteenth century, nursing was not considered a

suitable profession for a well-educated woman. Nurses of the time were lacking

in training, and they also had the reputation of being coarse, ignorant women,

given to promiscuity and drunkenness.

While Nightingale was on a tour of Europe and Egypt starting in 1849, she had

the chance to study the different hospital systems. In early 1850, she began her

training as a nurse at the Institute of St. Vincent de Paul in Alexandria, Egypt,

which was a hospital run by the Roman Catholic Church. March of 1854 brought

the start of the Crimean War, with Britain, France and Turkey declaring war on

Russia. Although the Russians were defeated at the battle of the Alma River, in

September 1854, The Times newspaper criticized the British medical facilities. In

response, Nightingale was asked by Sidney Herbert, the British Secretary for

War, to become a nursing administrator to oversee the introduction of nurses to

military hospitals.

Although being female meant Nightingale had to fight against the military

authorities at every step, she went about reforming the hospital system. With

conditions which resulted in soldiers lying on bare floors surrounded by vermin

and unhygienic operations taking place, it is not surprising that, when Nightingale

first arrived, diseases such as cholera and typhus were rife in the hospitals. This

25

meant that injured soldiers were 7 times more likely to die from disease in

hospital, than on the battlefield. Whilst in Turkey, Nightingale collected data and

organized a record keeping system. This information was then used as a tool to

improve city and military hospitals. Nightingale's knowledge of mathematics

became evident when she used her collected data to calculate the mortality rate

in the hospital. These calculations showed that an improvement of the sanitary

methods employed would result in a decrease in the number of deaths. By

February 1855, the mortality rate had dropped from 60% to 42.7%. Through the

establishment of a fresh water supply, as well as using her own funds to buy fruit,

vegetables and standard hospital equipment, the mortality rate in the spring had

dropped further to 2.2%.

Nightingale used this statistical data to create her Polar Area Diagram, or

"coxcombs" as she called them. These were used to give a graphical

representation of the mortality figures during the Crimean War (1854 - 56). A

coxcomb was divided into 12 colored wedges, to chart activity for a full year. The

area of each colored wedge, measured from the center as a common point, is in

proportion to the statistic it represents. The blue outer parts of the wedges

represented the deaths from preventable diseases. The inner red parts of the

wedges show the deaths from wounds. The black central parts of the wedges

represented deaths from all other causes.

Deaths in the British field hospitals reached a peak during January 1855, when

2,761 soldiers died of contagious diseases, 83 from wounds and 324 from other

causes making a total of 3,168. The army's average manpower for that month

was 32,393. Using this information, Nightingale computed a mortality rate of

1,174 per 10,000 with 1,023 per 10,000 being from zymotic diseases. If this rate

had continued, and troops had not been replaced frequently, then disease alone

would have killed the entire British army in the Crimea.

26

These unsanitary conditions, however, were not only limited to military hospitals

in the field. On her return to London in August 1856, four months after the signing

of the peace treaty, Nightingale discovered that soldiers during peacetime,

between 20 and 35 years of age, had twice the mortality rate of civilians. Using

her statistics, she illustrated the need for sanitary reform in all military hospitals.

While pressing her case, Nightingale gained the attention of Queen Victoria and

Prince Albert, as well as that of the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston. Her wishes

for a formal investigation were granted in May 1857 and led to the establishment

of the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army.

Nightingale hid herself from public attention, and became concerned for the army

stationed in India. In 1858, for her contributions to army and hospital statistics

Nightingale became the first woman to be elected to be a Fellow of the Royal

Statistical Society. In 1874, she became an honorary member of the American

Statistical Association, and, in 1883, Queen Victoria awarded Nightingale the

Royal Red Cross for her work. She also became the first woman to receive the

Order of Merit from Edward VII in 1907.

Abridged from an article by J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson.

Source: http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Mathematicians/Nightingale.html

Appendix: More about Charts and Graphs

There are many other graphs, besides general pictographs, that have been

around while they are not as common as those discussed in this section. For

instance, a stem-and-leaf plot (a stem plot, sometimes called for short) is

such a graph. A stem plot displays numerical data and estimates (the shape

of) the probability distribution from which the data came. It is very similar

to a histogram but it does this horizontally (instead of vertically in a

histogram).

A stem plot consists of a vertical line and digits on the left of the line and

digits on the right of the line, called stem labels and leaves respectively.

When a measurement in data consists of multiple digits, they are split up,

and some go to the left of the vertical line and become “stem labels” and

other digits go to the right of the vertical line and become “leaves.”

27

For instance, with data {{35, 49, 36, 40, 51, 47}}, the following stem plot

can be constructed.

These are stem labels.

3

5 6

4

0 7 9

5

1

These are leaves.

29.5

Stem-and-leaf plot

39.5

49.5

59.5

Histogram for the same data

Each row in a stem plot is a stem. There are three stems in the stem plot; the

first stem is labeled by the stem label “3,” the second stem is labeled by the

stem label “4” and the third stem is labeled by the stem label “5.”

The digits in the first measurement 35 are split up into 3 (which is the stem

label of the first stem) and 5 (which is the first leaf in the first stem), the

digits in the second measurement 49 are split up into 4 (which is the stem

label of the second stem) and 9 (which is the third leaf in the first stem), and

so forth. So, the leaf 7 must stand for the measurement 47. There are six

leaves. Thus, there are six measurements in the data.

A stem plot gives you pretty much the same information as a histogram of

same data. A stem plot is pretty much a 90o rotation of the histogram (see

the diagram above). However, a stem plot gives you more information such

as the sample size and original data, which is not the case with a histogram.

Of course, a stem plot becomes cumbersome with large data. Indeed, a

histogram would be a better choice for large data.

28

Instead of leaves (digits) in a stem plot or bars in a histogram, dots can be

used to indicate measurements and the height of a bar. These graphs with

dots are called dot plots (or dot diagrams). See the diagram given below.

3

● ●

4

● ● ●

5

●

●

●

●

1

●

●

29.5

39.5

●

49.5

59.5

These are dot plots

A dot plot gives you pretty much the same information as a stem plot and a

histogram. However, it gives you less information than a stem plot since it

cannot give the original data. On the other hand, it gives you more

information that a histogram since it gives you the sample size.

One advantage of dot plots over stem plots and histograms is that it can be

used for non-numerical data as well. That is, dots vertically lined up can be

used in the place of bars in a bar chart to make it a dot plots. Also, the dot

plot, in the diagram above, is made out of histogram using dots vertically

lined up, instead of bars.

Dots are commonly used, but there is nothing magical or special about dots.

For instance, if data about pumpkins are plotted, then pumpkins, instead of

dots, could be used to construct a dot plot (or a pumpkin plot) for the data.

Now suppose you love your dog. Then, even if the data have nothing to do

with dogs, you can use little pictures of your dog to construct a dot plot (or a

doggy plot) for the data. However, we are going into the realm of

pictographs at this point.

Bar charts and histograms are sometimes called column charts (since bars

make columns in these graphs). Bar charts and histograms given

horizontally are sometimes called row charts (since bars in these graphs

make rows). Again, a row chart and a column chart of the same data would

29

give the same information, but row charts are often considered as

pictograms. At any rate, a row chart should not be referred to as a bar chart.

There will be two more important graphs introduced in this course. They are

scatter plots and box-whisker plots (box plots, for short). Scatter plots are

for bivariate data and will be introduced and discussed in Section 4.1. Box

plots will be introduced and discussed, along with medians and quartiles in

Section 4.2.

© Copyrighted by Michael Greenwich, 08/2011.

☺

30